Mornings on the Speed River Trail

Finding nature in my own back yard.

Note: The photos in this blog were all made on August 9 and 10, during morning walks along the Speed River between the Hanlon Expressway and Edinburgh Road, Guelph, Ontario.

Great Blue Heron: splayed and dignified, Speed River, Guelph

OM-1 with Olympus 100-400mm f/5-6.3 at 400mm with Digital Teleconverter (efov 1600mm); f/11 @ 1/1600; ISO 1600; from jpeg files processed in Lightroom Classic. I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the quality that can be achieved with the OM System 2x Digital Teleconverter. The finest feather detail is not quite there, but otherwise, it is surprisingly good. It would certainly pass a ‘screen test’, considering that 99% of photographs are only ever viewed on screen. While the quality won’t meet the standards of a stock agency or the detail needed for a fine art print for framing, a canvas enlargement would be fine.

Living in a city has its conveniences, but as a landscape and nature photographer, I often feel claustrophobic surrounded by the necessary evils of pavement and traffic and suburbia and commercial-industrial strips. In Guelph, we are fortunate to have a few naturalized green spaces including the Speed and Eramosa River corridors through the city.

I’m always pleasantly surprised by the amount of wildlife found along the rivers. There are the usual characters such as Canada geese and mallards, but they are found just about anywhere, fair or foul. There are also a number of common songbirds, such as song sparrows, cardinals, robins, goldfinches, downy woodpeckers, catbirds, and in spring and early summer, orioles. In spring and fall, some of the migrants wander through making things a little more interesting.

What I find especially encouraging is seeing our resident great blue heron, two or three kingfishers and a couple of families of mergansers. These species tell me there must be healthy populations of frogs, tadpoles, and fish in the river to keep their bellies full. We even have an osprey that frequents the corridor west of Edinburgh Road – a real bonus. And, when I’m out early enough, I sometimes hear the splash of a beaver’s tail. In fact, the city has had to cage a number of trees to prevent them from becoming food and dam-building material. This is a good thing!

But, I’m not just looking for wildlife. There are a number of species of indigenous wildflowers through the seasons. The varied habitats of the tall grass prairie in the hydro corridor past Water Street and the riverine habitats along the Speed and Eramosa increase the overall biodiversity, another bonus for nature photographers.

The trouble is, I’m going for a walk to get some exercise. Going as far as Edinburgh and back is about 4km; to Gordon and back it’s 7k. The idea is to walk fast enough to increase the heart rate, but when a photo beckons, I need to stop.

Some mornings, I’ll take the 12-100/4 (efov 24-200mm). This gives me a moderately wide focal length for landscapes all the way to a medium telephoto for capturing natural details. It’s really the ideal walkabout lens.

Lately though, with the all the activity on the water, I’ve been bringing the 100-400/5-6.3. Despite the added bulk of a longer lens, it carries very well and is completely comfortable slung under my arm at the end of a ‘quick draw’ shoulder harness. More importantly, the lens handles well. Combined with the in-camera stabilization, I can comfortably and confidently shoot handheld at 400mm (efov 800mm). Perfect!

Now, I need to concentrate more on getting in a decent walk! But how can I with scenes and subjects calling out to me to be photographed! Furthermore, as the seasons progress, so too do the species on offer.

Thanks for reading!

If you have any questions or comments about the Speed River, naturalized areas in Guelph, OM System, raw capture, processing or anything else, please add it to the Comments section.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email so you are instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Photo Club or a personal field and/or screen workshop at Workshops.

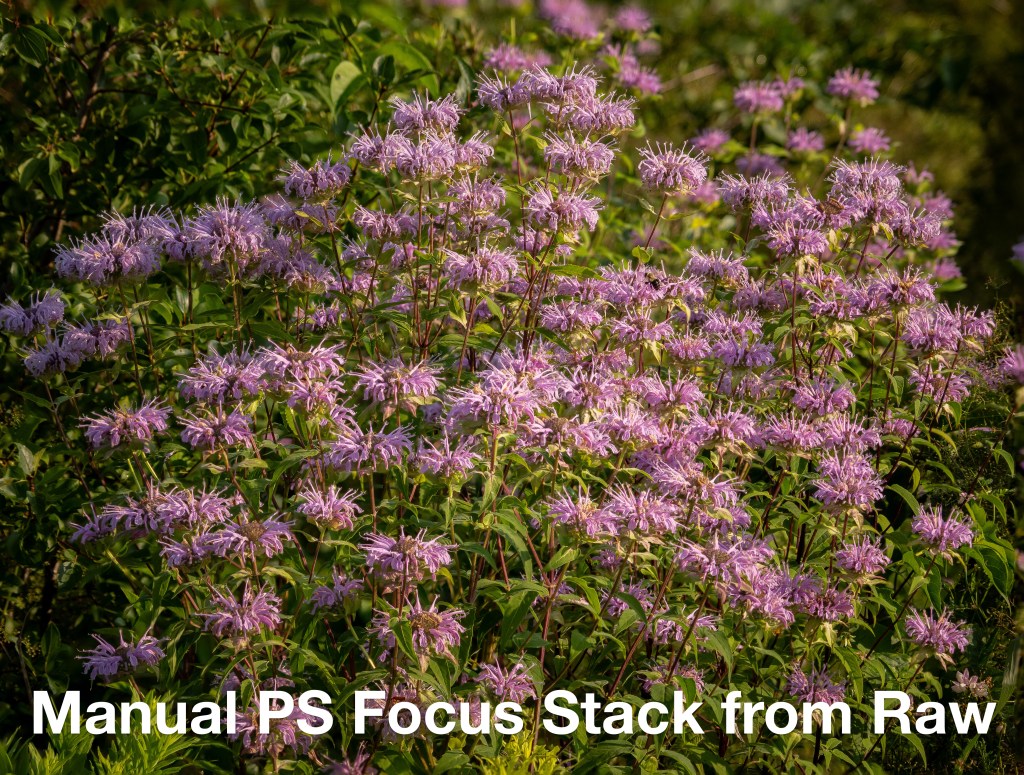

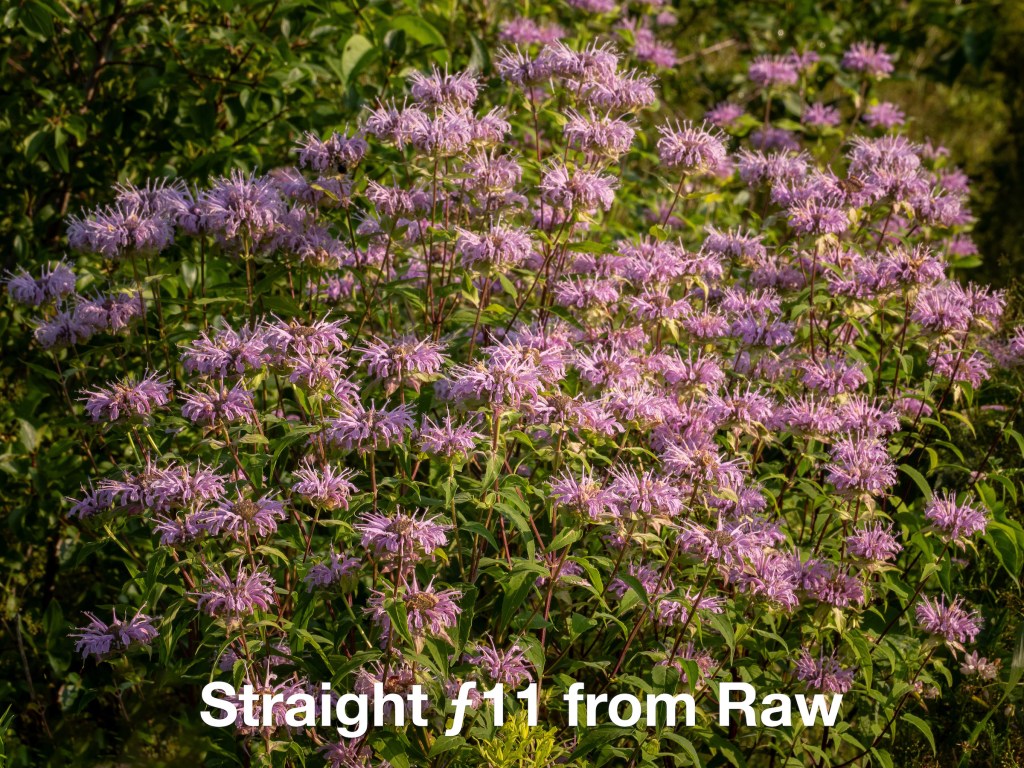

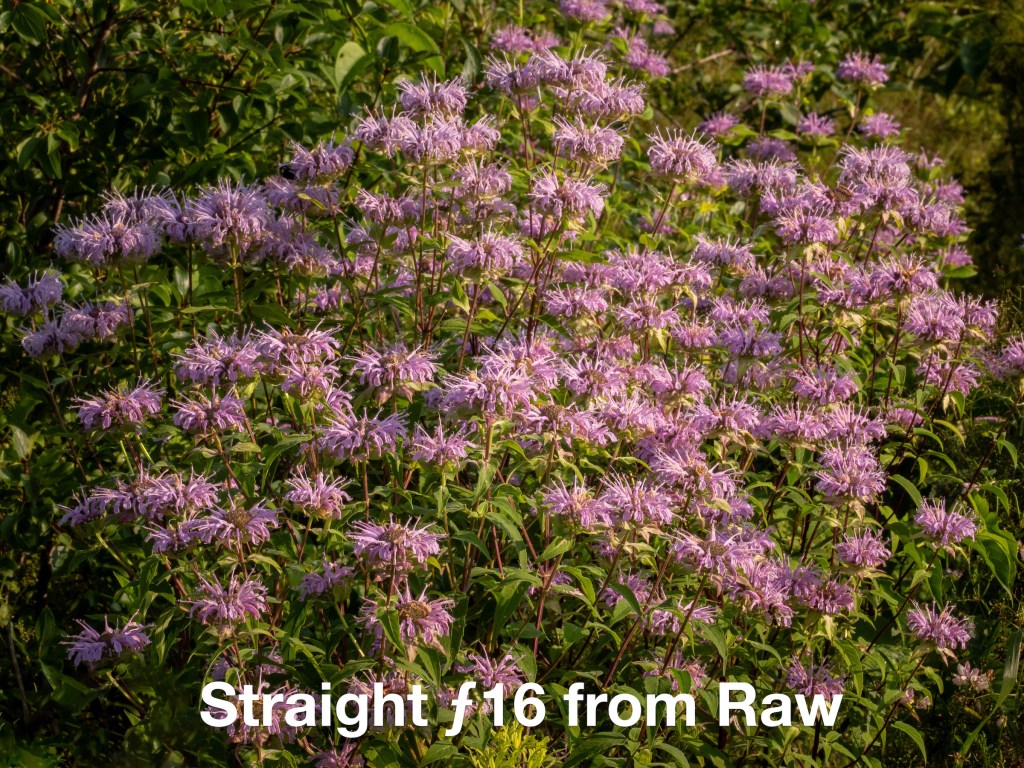

Some thoughts on Focus Stacking using the OM-1

Finally, I have some time to really delve into some of the computational features of OM-1, in this case Focus Stacking. I won’t blab on about what it is and all that since it has already been covered well by a number of photographers such as:

- Chris McGinnis (YouTube 3min);

- Peter Baumgarter (OM Photo Tips);

- Thomas Stirr (a variety of helpful blog posts); and

- Rob Trek (YouTube 13min)

This morning, I was walking along the hydro corridor at the end of Water Street, here in Guelph. This area was converted to a tall grass prairie habitat about 5 years ago and the city is working to maintain it as such. As a result, a number of wildflower species indigenous (native) to Ontario are now becoming established: foxglove beardtongue, wild bergamot, grey-headed (prairie) coneflower, Culver’s root, giant sunflower, black-eyed Susan, and tall coreopsis (tickseed).

OM-1 with M.Zuiko ED 12-100mm ƒ4.0 IS PRO at 100mm (efov 200mm);

ƒ8 @ 1/400; ISO 200; EV–1⅓; processed in Lightroom Classic

The wild bergamot was in full bloom with carpets of them covering the open area. My goal was to capture the light pink flowers and green foliage lit by the warm early morning light. Traditionally, I would have used a small aperture like ƒ11 or ƒ16 to achieve maximum depth-of-field, or even ƒ22 with a full frame camera. But small apertures increase the risk of defraction leading to a softening of details. This happens with all cameras, but with Micro Four Thirds sensors, it kicks in at about ƒ8.

No worries. I still shot at ƒ11 and ƒ16, just to see how far I could push the system, also knowing that some of that lost detail may be recoverable with appropriate sharpening of the raw file. However, this was also a great opportunity to try the in-camera ‘computational photography’ mode called Focus Stacking. For that, I set the lens to ƒ4 and Focus Stacking to 10 shots with a focus differential of 4. These settings are what Thomas Stirr recommended in one of his recent articles, so it seemed like a good place to start. I focussed on the closest part I wanted in focus and presses the shutter release. The 10 photos were made in quick succession, then processed in-camera. In about 20 seconds I had a finished JPEG.

Let’s get to some comparisons. All images were processed in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom Classic. One is a straight shot at ƒ11, the second at ƒ16. Of the two Focus Stacked images, one was made using in-camera Focus Stacking, which is automatically saved as a JPEG; the fourth was created manually in Photoshop using the same series of Raw images the camera used:

Take a moment to have a look at each image:

- Tap or click on on any image above to open the Gallery to that image. I recommend starting with the ƒ11 image.

- Scroll through the Gallery looking at each in turn.

- While the Gallery is open, double tap on an image to see it zoomed in. Then scroll through again, looking at each image zoomed in.

What do you think? What did you notice?

If you’re like me, aside from the JPEG being slightly soft, there is not a lot of difference. The ƒ11 and ƒ16 images look surprisingly good, even zoomed in. All three images made from directly Raw files look perfectly fine when viewed without zooming. And, let’s face it, that’s how most images are viewed – on screen, at screen size or smaller. Here are the same 4 images re-sized to 2400px on the longest side. I think you’ll find the differences virtually disappear; even the JPEG looks great.

A note about the JPEG. In-camera JPEGs from the OM-1 are touted as being some of the best in the business. Originally, my JPEG looked like like crap. I only realized why as I was writing this blog. I have my in-camera ‘Picture Settings’ set to ‘Muted’ with saturation at –2. I never shoot JPEGs, so this is done to get more accurate-looking previews of my Raw files on the LCD, which are only ever shown at JPEGs on the LCD. Originally, the colours of the JPEG did not accurately reflect the quality possible, so the file underwent a little more adjustment than is typical. HOWEVER, perhaps like you, I am disappointed with the sharpness of the JPEG,. Despite having sharpening added in Lightroom, it is not a crisp and lively as the image made from Raw files. I think I will stick with capturing Raw files for the foreseeable future!

JPEG vs Raw aside, upon closer examination with a more critical eye, slight differences between the four images become apparent :

- The manually created focus stack using Photoshop is sharper and more lively-looking. It also includes the whole frame, versus the in-camera JPEG which is cropped, and t appears to have less noise. It is definitely a superior product.

Note: Each of the images that are automatically made and saved as Raw files by the OM-1 were shot at ƒ4 @ 1/800 at the OM-1’s optimal ISO of 200. - The ƒ11 capture was made at 1/100 at ISO 200; the ƒ16 image was made at 1/50. This highlights one of the advantages of Focus Stacking: each image is made at a more optimal (sharper) aperture – ƒ4 – with no fear of diffraction. Furthermore, a faster shutter speed virtually eliminates any concern for blur from camera shake or a wind-blown subject. That being said, focus stacking really must be done with static subjects as subject movement between frames will degrade the stacked image.

- One further advantage of manually stacking the images is the opportunity for fine-tuning. For example, I did not send all 10 images to Photoshop for stacking. Of the 10, I selected only 5 in the middle range that captured the area I wanted in sharp focus. The result shows up in the very top of the image: you’ll note the background flowers and foliage are far more out of focus than in any of the other photographs. Subtle, but there. This is done on purpose to focus the viewer on the grouping of flowers in the foreground. Further editing of the layer masks in Photoshop is also possible, though I can’t see tackling anything like that any time soon.

The images above are re-sized to 1600px on the long side.Tapping or clicking on any one of them will open the gallery.

All three photographs were made in Photoshop by processing the in-camera Focus Stack Raw files. Prior to that, each set of files was processed in Lightroom. The first two are of Wild Bergamot; the third is Culver’s root. With the Culver’s root thoroughly surrounded by a sea of grasses, I would normally try to isolate such a complicated flower from the background, but that was impossible. Going the other way by including that sea of grass seemed like the best option.

So, what have I learned?

- I feel Raw files stacked are still better than the in-camera JPEG, which to me isn’t all that surprising. However, the difference is less than what I expected (see below).

- Using ƒ11 in a “straight” photograph (e.g. without Focus Stacking) provides more than adequate image quality after thoughtful sharpening is applied (even ƒ16 in a pinch), though Focus Stacking provides a consistently higher-quality result;

- Focus Stacking requires:

- a large aperture, such as ƒ4 or even ƒ2.8, which is a good thing, as it allows a faster shutter speed;

- fairly still conditions, though that’s the case for most serious detail work in nature. Shooting full frame at, for example, ƒ22 would have lowered the shutter speed to 1/25, meaning little tolerance for wind.

- Focus Stacking, both in-camera and with Photoshop, struggles with more visually complex scenes such as thin stalks of grass in the foreground. This is an area I will need to explore further, perhaps with a smaller differential and more images being captured. But I also think that with narrow blades of grass in front of narrow blades of grass,Photoshop struggles with identifying what’s sharp and what’s not and masking accordingly.

- I don’t really need to use in-camera Focus Stacking as capturing a series of files using Focus Bracketing is available on the OM-1. That way, only raw images are captured for later assembly using Photoshop. (For some reason, the OM-1 is saving both Raw and JPEG files of each exposure, even though I have Raw only selected as a file type.)

- Focus Stacking allows up to 15 images to be captured; Focus Bracketing is more flexible, allowing up to 999 (!) sequential captures – far more than I could ever imagine working with, but it would certainly make a great future project!

Focus Stacking using Photoshop is a quick and viable way to further increase image quality and to customize the out-of-focus areas of the image. My workflow is very straightforward:

- Import files into Lightroom;

- When dealing with a lot of images, I set-up an Auto-Stack:

- Photo > Stacking > Auto-Stack by Capture Time and set it to 3 seconds as, typically, all the files are created within that time frame;

- Select and delete unnecessary JPEG;

- Choose one of the raw image file for processing and apply the adjustments I typically make to ‘breathe life back into the machine-made file’, including Basic, Colour, Detail, Adjustment Masks, etc.;

- Sync changes to the others;

- Select the Raws to stack;

- Photo > Edit in > Open as layers in Photoshop . . .;

- In Photoshop:

- Select all the layers;

- Edit > Auto-Align Layers > Auto;

- Edit > Auto-Blend Layers . . . > Stack Images;

- Layer > Flatten Image;

- File > Save As . . → Here I replace “Edit’ in the filename with as FS to indicate focus-Stack. The file is immediately visible in Lightroom.

- I select the PSD file and choose Photo > Stacking > Move to top of Stack;

- Photo > Collapse Stack. Job done, usually in a minute or so, after processing.

That’s 12 steps more than my normal workflow, but other than the processing, the steps are all very mechanical. The Photoshop steps could be saved as an Action (which I have done).

Here is another example. The image below is of a very complicated scene for successful Focus Stacking. There are many thin blades of grass overlapping, both in the foreground and in the background. One image is the in-camera JPEG; the other was produced using Raw files and Photoshop. Drag the centre button to compare the two. Which is which? Which one do you like better?

The complexity of the scene above fooled both the camera and Photoshop during stacking. However, the point of showing this image is to demonstrate just how good an in-camera Focus Stacked JPEG can be. I’m impressed. BOTH images have been processed in Lightroom prior to being re-sized to 2400px on the long side. The image on the LEFT is the JPEG produced in-camera; on the RIGHT is the Photoshop-made Focus Stack. Here is a 100% crop to compare more precisely:

I am greatly looking forward to pursuing Focus Stacking, or rather Focus Bracketing and Stacking. The OM-1’s implementation of these features using computational photography provides the necessary precision and repeatability for proper testing and predictable results. Given my interest in natural details and landscape photography, Focus Stacking has become an essential addition to my ‘photographic toolkit’, It is a reliable method of improving image quality with very little increase in effort.

Iceland Follow-up – Photo assessments

I had a difficult time preparing the Iceland blog, mostly because of the photos. While I was generally pleased with the results, if I were to objectively assess the photos, I would give many of them a C, a few a B, only 1 or 2 an ‘A’, with only 1 A* / A+ photo.

In retrospect, many of the photos included in the blog are “I was here” shots. They are technically competent depictions of the scene in front of the camera, but they don’t see beyond the obvious, which for me is the mark of an engaging and compelling photograph. For most of the photos, the word “illustrative” comes to mind. Thank goodness Iceland is so forgiving. It is so dramatic that even a “meh” photograph has visual merit and the potential to engage the viewer.

Being responsible for a group and being in a ‘coach tour’ situation has that effect on photography. Rarely did I have more than a few minutes to devote to thoughtful, more interpretive photography, hence the dearth of ‘As’. However, this was not a photography tour. My mission, to introduce a group of active and enthusiastic teens to the thrills and challenges of foreign travel in a captivating and adventurous location—and bring them all back alive and well—was a complete success.

The ‘C’ photos:

Technically competent, illustrative in nature; the kind of photo where you go “Nice”, then scroll past.

The ‘B’ photos

Technically competent, with some interpretive value. More than nice to look at, the viewer will spend a little longer with ‘B’ images, perhaps to examine details.

The ‘A’ photos

More interpretive than illustrative, ‘A’ images show some personality and cause viewers to stop and ponder. They engage the viewer, if only for a few moments. These would be considered for printing and framing and exhibition, more or less held in reserve

The A* / A+ photo

To me, an A* / A+ images go well beyond a textbook capture, verging on the abstract. They engage the viewer and compel them to think beyond the where? to the how? and why?, perhaps even the what? It is these images that are instantly worthy of printing and framing and exhibiting. In this case, I have two variations on the same theme.

Thanks for reading!

If you have any questions or comments about Iceland, photo techniques (the “how to”), assessing photographs, or anything else, please add it to the Comments section.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email so you are instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Photo Club or a personal field and/or screen workshop at Workshops.

Iceland, June 2023

Iceland: the land of fire and ice. To photographers, this rock in the North Atlantic is a gem. Simply put, there are more dynamic and engaging natural landscapes and photo ops per square kilometre in Iceland than anywhere else I’ve travelled. And most importantly, they are accessible by car and/or a short walk or hike.

OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko Digital ED 12-100mm F4.0 IS PRO at 14mm (28mm efov); f/4.5 @ ¼; ISO 200; Circular Polarizing filter; EV–⅓; Live ND mode used to blur motion in the water

Iceland’s raw beauty is the result of plate tectonics and volcanoes producing masses of lava—a new fissure is erupting as I write this—the constant grinding by massive glaciers flowing down mountain valleys, and the relentless flow of numerous rivers, sculpting cliff faces and scouring broad flood plains. For photographers, these forces create evocative and evolving landscapes of contrasting colours, shapes and patterns.

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 16mm (32mm efov); f/8 @ 1 second; ISO 200; EV–⅓; Live ND mode

“Gull” = golden; “foss” = waterfall; “á” = river. Therefore, this is the Golden Waterfall on the River Hvít

Ancient azure blue glacial ice leaps from the rich, blacks sands of eroded lava. Bright snow or blue sky contrasts with the soft reds, oranges and ochres of lava charged with iron and sulphur compounds. Emerald green grasses and mosses cling to beds of brown-black lava soils, punctuated with blazes of pink and yellow summer wildflowers. Brilliant white water cascades carve chasms into cliffs and gorges, spilling out over the landscape in the ever-changing ribbons of braided streams and rivers. Now, add to those scenes some stocky Icelandic horses, a pure and ancient hardy breed with their long, wind-blown manes, and some woolly white and black Icelandic sheep—ideal for anyone with a camera; an endless paradise for the die-hard landscape photographer.

Details along the trail, Reykjadalur

In June 2023, I was the trip lead for a group of 30 energetic teens, 3 chaperones, and our Evolve Tours guide for 7 very full days of touring and hiking the most commonly visited places in Iceland. The overnight flight from Toronto landed at Keflavík at 6:30am local time, which is 2:30am Toronto time. But, as you do when travelling, you hit the ground running.

Photo Tip: While on the flight to Iceland, keep an eye out for the dramatic mountains and glaciers of Greenland on the north (left) side of the plane. In the summer months, with the Midnight Sun of the Arctic, the light will be warm, even dawn-like. You may find it worth selecting a window seat on that side, typically seat “A” or, for the homeward flight, seat “F”, preferably ahead of the wing. As with everything photographic, there is no guarantee the weather will co-operate.

I did this same trip six years previously with a school group, as well as travelling for two spectacular weeks in March a few years ago with my wife, Laura. She’s travelled to Iceland an additional 2 or 3 times herself. Can you tell we love Iceland?

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 16mm (32mm efov); f/5.6 @ 1/60; ISO 200; EV 0

Still bleary-eyed from the the flight, we wolfed down some breakfast at the bus, then we were off to see the sights of the Golden Circle Route: the tectonic fissures and historical setting of Þingviller National Park; the hot steam jets of Geysir, and the largest waterfall in Europe, by volume, Gullfoss. This, along with the “Waterfall Route”, which we did on Day 3, (Skógafoss and Seljandsfoss) are the most frequently-visited places in Iceland as they are all within day-trip distance of Reykjavik.

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 16mm (32mm efov); f/9 @ ⅛; ISO 200; EV–1⅓; Live ND mode

Reducing the amount of sky in the composition, then adding a sky mask during editing allowed me to bring some definition back to the clouds

Our first base, though, was a guesthouse south of Selfoss, about an hour southeast of Reykjavík along Highway 1, the Ring Road or Hringvegur. This gave us the freedom to backtrack slightly to visit the Hellisheidi geothermal power plant and hike out to the Reykjadalur hot springs on Day 2

Photo Tip: Phones, watches and tablets automatically update to different time zones; most cameras do not. Before landing, take a moment to set your camera to the time and date of your destination. Iceland is GMT 0 and, with nearly 24 hours of daylight in the summer, it does not observe Daylight Savings Time or Summer Time.

One of the difficulties with Iceland is the weather. Be prepared for the worst—overcast, rain and wind—and hope for better. Icelanders will tell you, “If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes”, an allusion to how variable it is. The problem is there can be days of overcast skies with light to heavy rain, sometimes calm and sometimes windy. This is what we experienced for most of our trip, counting the sunshine in minutes. In fact, we cancelled our day on Heimaey, in the Vestmannaeyjar Islands due to constant rain and near gale force winds. The ferry trip, alone, would have done us in.

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 16mm (32mm efov); f/9 @ ⅛; ISO 200; EV–1⅓; Live ND mode

Yes, another dreary day. This took some careful editing in Lightroom to separate sky and falling water.

As a photographer, what to do? As I said, prepare for the worst and hope for something better. “Preparation” takes two forms: mentally and physically. If you go to Iceland expecting the weather to co-operate, to provide you with dramatic blue skies mixed with soft, golden sunshine, you will likely be frustrated. Those days do happen, more so in summer than at any other time of year, but be mentally prepared to adjust your expectations.

Consider changing your schedule to better fit the weather or change the nature of your shooting. Reduce the amount of sky in your landscapes, concentrating more on colour contrasts, shapes and natural details. Consider also the details: those “blazes of pink and yellow wildflowers” pop with rain drops against the bright green grasses and mosses and dark lava soils.

Photo Tip: With overcast skies, isolate portions of waterfalls against the dark volcanic rock. Expose carefully then check for highlight clipping on your LCD; adjust as needed and shoot again. When you include an overcast sky, again, carefully check for highlight clipping and reduce exposure accordingly. Alternatively, use HDR techniques to capture the full tonal range. Either way, with some post-capture masking and editing, overcast skies can be tamed to enhance the contrast.

The other aspect of preparing for rain is the physical aspect of protecting equipment. My colleague on the trip used light plastic rain protectors which worked okay, but they also flapped around in the wind. A heavier, tighter fitting rain cover may have solved the issue. I chose to go au natural, and am pleased to report that the weather sealing of my OM System gear is excellent, though I also took precautions.

Another key piece of equipment you’ll need, rain or shine, is a soft, lint-free, absorbent cloth to wipe down your gear, especially the front filter or lens element. Wind and waterfalls, and sometimes just waterfalls, will ensure you and your gear will get a thorough soaking. At Gullfoss and Skógafoss the spray is relentless, and at Seljandsfoss, it’s completely unavoidable as you walk and climb behind the waterfall. If you make it to Gljúfrabúi, the hidden waterfall near Seljandsfoss, you and your gear will be thoroughly soaked.

My third rain prep suggestion is about your camera strap. Expecting I would be in a fleece and raincoat most of the time (which proved correct!), I switched my usual neck strap for a “quick draw” shoulder harness. This meant the camera could easily be tucked under my right arm, zipped inside my raincoat when necessary, but always be ready-to-go in an instant. That shoulder harness is the best $25 I’ve ever spent on photography. Even better is how easily I can unscrew the strap from the tripod socket to free-hold the camera, my other favourite way of shooting.

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 18mm (36mm efov); f/8 @ ½; ISO 200; EV+1; Live ND mode

I’m often asked about what lenses to bring when travelling. Previously, I used a Sony RX-10iii that covered 24mm to 600mm with a beautiful Zeiss lens and a 1″ sensor. It was a great travel camera that I can highly recommend. More recently, I’ve moved into the OM System, specifically chosen for its high quality and portability.

The OM-1 and my kit of three high-quality zooms covering the full frame equivalent of 16mm to 800mm all fit into a small sling pack weighing about 4kg (less than 10 pounds). So I bring everything. However, during this most recent trip, I used my 12-100mm/4 (24-200mm efov) almost exclusively, only exchanging it for my 100-400 (200-800mm efov) to capture close-ups of a seal in Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon. If there had been puffins or other seabirds, the 100-400 would have seen more use. If the weather and timing were on my side, and I wasn’t herding 30 teens, I would have made better use of my 8-25mm/4 (16-50mm efov) zoom to create more dramatic landscape shots.

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 12mm (24mm efov); f/5.6 @ 1/500; ISO 800; EV–⅔

It was so windy on the top of this “hill” I had no choice but to increase the ISO to get a fast enough shutter speed!

In our seven days, we covered a lot of ground and did a lot of hiking. A few commercial “extras” we included in the trip were:

- A tour of a lava tunnel at Raufarhólshellir. It was educational but not ideal for photographers due to the short time in the tunnel;

- Taking an amphibious craft out onto Jokülsárlón glacial lagoon where we got close up to brilliant blue icebergs and a seal;

- A glacier hike on Sólheimajökull glacier; great for black and whites with a touch of blue. I preferred our glacier hike on Svínafellsjökull years ago with its more dramatic location, though I understand it has retreated significantly;

- A popular hiking destination, but one that requires 4×4 vehicles (we had a 4×4 coach!) is Þórsmörk. The image above gives a sense of the outstanding and dramatic beauty of this extensive wilderness area. The road in is loose gravel, “organized” each year into a semblance of a road after the spring runoff. I lost count of the number of river crossings the coach had to make as there are no bridges in this region. Surprisingly, there is public bus service into the Þórsmörk region, but you need to be prepared for wilderness.

- On our last school trip, we visited Landmannalaugar, an equally spectacular wilderness region that also requires a 4×4 vehicle for access.

- The Blue Lagoon; very expensive, but it’s what they wanted!

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 15mm (30mm efov); f/5.6 @ 1/125; ISO 200; EV 0

Only the blue of the Atlantic Ocean and a hint of green on the distant slopes provide colour to an otherwise surreal and desolate landscape.

There are a few favourite places that I am looking forward to getting back to for more serious photography:

Brúarfoss is the spectacular glacial-blue-water waterfall just east of Laugarvatn, on the Golden Circle. With a new road and parking area, this place will soon become inundated with Instagrammers.

Breiðamerkursandur, also called Fellsfjara, is the black sand “Diamond Beach” across the Ring Road from Jokülsárlón glacial lagoon. It is here that icebergs large and small wash ashore, having calved off from Breiðamerkurjökull glacier and floated through Jokülsárlòn. As a photographer, you can well-imagine the photographic potential of combining clear, white, and blue ice with black sand and gravel. Add the waves piling in from the North Atlantic, and you have a few hours of photo riches to discover and create.

The same is true at Reynisfjara black sand beach near Vík, but here you need to be extra cautious of rogue waves which are known to sweep tourists away. Seriously!! The basalt columns along the shore and the various eroded cave features create another treasure trove of interesting photos.

These are just a few of the many dozens-hundreds of photo ops available to anyone with a creative eye who can work with the weather and the colours, shapes and patterns of the various landscape elements to create truly engaging photographs. Iceland really is a land made for landscape and nature photographers.

On ice: Harbour Seal, Joküllsárlón

OM-1 w/M.Zuiko Digital ED 100-400mm F5.0-6.3 IS at 400mm (800mm efov); f/6.3 @ 1/1250; ISO 1000; EV 0. The internal stabilization of the lens and camera combined to make these shots possible with an 800mm field of view on a rolling boat.

A few tips if you are thinking of visiting . . .

Since I was with a school group, we did a coach tour. Our personal trips have all been self-drive. If you’re thinking about Iceland, I strongly advise booking a rental car and BnBs or guesthouses and spending a week or more. There is more than enough spectacular scenery and experiences to see and photograph without a four-wheel-drive. Even in March we rented a small car and had little trouble touring the north of the island. The roads were no worse than our Canadian roads in winter.

A car gives you the flexibility to stay longer at places when the shooting is good or move on (or hide out in) during bad weather. You can start as early in the day as you like and keep shooting ‘til midnight. Oh, and if you’re there in the summer, don’t go looking for the Aurora borealis! Icelanders turn them off until the fall, when the sky is dark enough at night to see them. It’s a way of promoting tourism in the off-season.

Meals out can be expensive, but once you realize taxes are already in the price and tipping is not a thing in Iceland (everyone earns a decent wage there), the prices aren’t too far off any touristy place. Save yourself some coin by shopping at Bonús, and make at least some of your meals at your BnB. Some Icelandic foods you really must try include Kjötsúpa, a lamb and vegetable soup similar to Scotch broth; Plokkfiskur, a traditional fish and potato stew; and their amazing liquorice ice cream—in fact all their ice cream is phenomenal! There’s a gas station near Svínafellsjökull Glacier in Vatnajökull National Park that has a great cafeteria with Icelandic food called Veitingasala Restaurant, Shop and Gas—highly recommended.

OM-1 w/12-100mm/4 at 57mm (114mm efov); f/4 @ 1/80; ISO 200; EV–⅓

The black is ash from the eruption of Eyjafjallajökull in 2010.

When we travel to Iceland ourselves (without students), we find the BnB/guesthouse experience far more enriching and flexible. We book in central locations (Selfoss, Laugarvatn, Kirkjubæjarklaustur, Vík, Ólafsvík, etc.). We stay a few nights at each location, and explore from there. A great way to finish the day is by going to a local geothermally-heated pool with hot tubs. They are typically outdoors—a wonderful experience when it’s snowing in March! The commercial hot springs—Sky Lagoon, Hidden Lagoon and Blue Lagoon—are lovely but very expensive. However, a 1-hour-hike up Reykjadalur (near Hveragerði) will take you to a natural hot spring, for free, as are the numerous other natural hot springs around the country.

In fact, be wary when you visit Iceland travel websites. You will be bombarded with commercial experiences that cost $100 to $800 or more. In reality, all of the outdoor landscape and walking/hiking experiences are free, other than the cost to park your vehicle (about $10/day at a National Park) and some toilet facilities (by card or coin, $1 to $3 per use).

The culture in Iceland is rich and ancient. The landscapes breathtaking. And the people are warm, forthright and confident, thoughtful and creative. Mass tourism in Iceland is still a relatively new phenomenon, so don’t get upset if you are told off for stopping at the side of the road for a photo or worse, pulling into someone’s farm lane. They don’t appreciate roadside pees either. And watch your speed! 90km/h is 90km/h, not 100 or 110 like it is here in Canada. The roads are narrow enough without having a wide-eyed tourist driving with only half an eye on the road while scouting for just the right spot for a photo. Most importantly, once you return home, begin planning a second trip because once is never enough!

Further Reading and Planning (and Dreaming!)

Caveat: Like every travel website, the photos shown on these and many other websites show each location at its best. Many photos have also been shot with drones, which are not permitted in popular travel areas and national parks without a special permit. Weather is also highly variable in Iceland and can be used to your advantage in photography , but it can also be disappointingly rainy at the wrong time.

- Iceland Travel: Scenic Routes in Iceland – This is the official travel website of the Iceland government. I like it because the maps and info are very helpful and there are no ads screaming for attention as with so many commercial sites. We visited the Golden Circle route and the South Coast route. I can also highly recommend Snæfellsnes and the North, though really, you can go anywhere and be astonished at the beauty.

- Lonely Planet: Iceland – My second go-to site for Iceland newbies

- Iceland Weather: Your phone may have weather showing right on the Home Screen, and while it may be accurate most of the time and in your home country, it may not be accurate locally in Iceland. The Iceland weather service has a much more reliable website and phone app, which also includes earthquake and avalanche updates.

- SafeTravel.is is a website and phone app designed to provide you with local updates to help keep you safe. It is particularly helpful if you are self-driving.

- Vatnajökull National Park covers an extensive part of the south coast with many viewpoints and glaciers accessible by “easy” half- and full-day hikes. Skaftafellsstofa Visitors Centre is a great place to start with the well-interpreted Glacier Trail and the Svartifoss Trail. Further east is Fellsfjara black sand “Diamond” beach with icebergs washed up from Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon, where tours of the lagoon are available (for a fee) on an amphibious craft, a zodiac, or by kayak.

- Drone Use in Iceland – Although a commercial website, it has the most complete set of rules and regulations. Note that additional rules will be implemented “soon” to comply with EU rules regarding registration of drones and pilot training. You will need to register at flydrone.is and pay the ISK 5,500 (CAD 60) fee.

Notes:

- efov: Equivalent Field of View for a full-frame digital camera or 35mm film camera.

The advantage of the smaller Micro Four-Thirds sensors is that an Olympus 400mm lens captures the same field of view as an 800mm lens on a full-frame camera. This means size and weight are greatly reduced and the handling of long lenses and image stabilisation are far superior. - All images are saved as RAW files then are processed using Lightroom Mobile and Lightroom Classic. Jpegs out of the camera just don’t cut it with me. I have never met an image that doesn’t benefit from some thoughtful post-capture processing; it’s the equivalent of breathing life back into a machine image.

Thanks for reading!

If you have any questions or comments about Iceland, M43s photography, OM System, efov, raw capture, editing or anything else, please add it to the Comments section.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email so you are instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Photo Club or a personal field and/or screen workshop at Workshops.

The Myth and Reality of Small Sensor Noise

Is noise a real or imagined problem? How well can noise be ‘cleaned up’ whether it’s necessary or not?

As you know, I have ventured into the realm of small sensor photography, having traded in my Nikon full frame system for the OM Systems OM-1 (formerly Olympus) camera body and lenses. With a smaller sensor comes the concern, real or imagined, of greater noise, especially at higher ISO settings. And we all know, more noise translates into poorer quality photographs. So why would I bother with a small sensor camera?

OM-1 w M. Zuiko Digital 100-400mm ƒ5.0-6.3 IS at 400mm; ƒ6.3 @ 1/2000; ISO1600

Small sensor pros. Any cons?

The OM-1 comes packed with 20.2 million pixels on a sensor that is ¼ the size of a full frame sensor. At this pixel density, if it were a full frame camera, the sensor would be about 80mp, something Sony and Canon have yet to achieve. The smaller Micro Four Thirds sensor is why a 100mm lens on an OM-1 gives the same field of view as a 200mm lens on a full frame camera. Small sensor = shorter focal lengths = smaller lenses = less weight in my sling pack, which is why I traded in my Nikon full frame for the OM system.

However, each of those 5184 x 3888 pixels is smaller in size than the pixels on, for example, a 46mp full frame camera like Nikon’s Z9. Each pixel (or photo receptor) on the OM-1 sensor is 3.36 microns in size; for the Nikon Z9, it’s 4.35 microns. Being 2 microns smaller, the photo receptors on the OM-1 cannot gather as much light per exposure. Therefore, the “gain” needed to boost the signal from the sensor to the digital file is higher, resulting in more noise. At least that’s the theory, but does it bear out in actual practice?

OM-1 w/100-400mm ƒ5.0-6.3; ƒ11 @ 1/200; ISO400

As the Grinch complained, “Noise! Noise! Noise!”

In theory – noise! However, the reality is that the noise level of files from the OM-1 is truly impressive. In fact, it is so good, I find myself examining photos at 200% for noise and sharpness, rather than at 100%. And, when printed, any noise visible on screen disappears, even at ISO 1600. Moreover, Mike Lane, a British wildlife photographer, is so impressed with the noise on his OM-1, he uses ISO 1600 as his base ISO. I remember the days (okay, old man) of pushing ISO 400 Tri-X black and white film two stops to ISO 1600 and having to deal with the salt and pepper results of grain on top of grain. Well, not anymore!

The engineers at Olympus, and subsequently OM Systems, have built some advanced electronics into the camera to deal with noise, including 3 analog-to-digital converters (ADCs). These are the electronics that boost the signal from the photo receptors before being written to a file. Each ADC is optimised for a different ISO range: ISO 200 to 800; ISO 1000 to 12800; and ISO 16000 and above.

Incredible. Now, I will admit up front that I have not tested these ranges. Rather, my findings are based on actual usage in the field. Here are my findings using photos shot at ISO 3200.

I can honestly report that noise is more visible on files from the OM-1 than files from my D800E, BUT . . . and this is an important but . . . the noise is neither objectionable, nor noticeable, except at 200% viewing on screen – and this is the issue. If it takes pixel peeping at 200% to see noise, then it really is a non-issue. 95% (or more) of photos taken are destined to be viewed on a screen and NOT at 100%. A whole photo online is often at values of 10%, 25% or maybe 50% for the largest screens. As an example, my 16.2″ MacBook Pro has a resolution of 3456 x 2234 pixels or about 7.7mp. A full-sized photo would be viewed at about 38% of its actual size. The photos you see here are downsized to 1200 pixels on the longest dimension. Definitely no noise at that size! So noise is a non-issue.

OM-1 w/100-400mm ƒ5.0-6.3 @ 400mm; ƒ6.3 @ 1/800; ISO3200; EV-⅔

Other than the jpeg artefacts from the conversion and downsizing, the noise visible at 200% is simply not visible in this image. Below is a 100% crop of the same ORF as processed in Lightroom without the new IA Denoise. You can begin to see the grain (it is ISO 3200, after all), but it is completely within the normal parameters of image viewing.

The noise issue, or non-issue

The problem is that noise has been made into an issue by internet pixel peepers who unrealistically view images at 100% and 200%, then make grandiose statements about noise. But what about large prints?

The other 5% (or less) of images are printed either in books or as photographic prints and enlargements. Once again, noise is a non-issue. In any print up to 11×14″ (which would cover all books and about 95% of all wall-hung prints), noise is not a factor. Not in the least. If you absolutely need to, image files can be up-rezzed before printing. For prints larger than 16×20″ noise becomes a factor only amongst the pixel peepers. In fact, wedding and portrait photographer Joseph Ellis makes prints up to 2’x3′ “even without much care or thought to the process”.

Even as far back as 2018, there was no recognisable difference between large prints made with full frame and Micro Four Thirds cameras (see Full Frame vs Micro 4:3 – Where It Matters Most). Why? It’s the content of the photograph that matters, not the noise. It has long been recognized that the only people who really pay any attention to noise on prints or in files are pixel peeping photographers, not clients. Clients are taken in by the emotional response they have with the content of a photograph. So, across the board, professional photographers using Micro Four Thirds sensor cameras are in no way disadvantaged by the pixel dimensions or the noise of their images.

OM-1 w/M. Zuiko Digital 12-100mm ƒ4 IS PRO at 100mm; ƒ8 @ 1/160; ISO200; EV-⅓

Topaz, DxO, OM Workspace – What to do?

Before switching to an OM Systems camera and lenses, I had to think long and hard about the issue of noise and sensor size. Coming from full frame, I had “drunk the Kool-Aid” regarding the limits to small sensors. Furthermore, I like big prints. So, I spent a lot of time reading articles and viewing videos about the use of Topaz DeNoise AI, DxO PureRaw, and DxO PhotoLab, almost to the point of ordering one of them to safeguard my small sensor files against noise.

Upon purchasing my OM-1 I was pleased to learn OM Workspace (OMW) – their proprietary raw editing app – had AI Noise Reduction. Problem solved? Yes. OMW’s AI Noise Reduction and Sharpening modules worked their magic, beautifully eliminating noise while maintaining sharpness.

Initially, my only concern was that my 20mp raw files bloated to 60+mp 16-bit TIFF files, as TIFFs were the only way to export the improvements back to Lightroom for further processing. Then, I began to discover that shadow recovery in TIFF files is very poor compared to what I can do with raw files. And worse, the shadow recovery in OM Workspace, prior to exporting as a TIFF, was rudimentary at best. Combine this with a lack of Auto Black Point and Auto White Point adjustments, and my initial positive impressions of OMW waned, so the hunt for a better process continued.

Both Topaz and DxO were very tempting alternatives, mostly to avoid using large 16-bit TIFF files from OMW, and maintain a raw workflow. But which one should I order? DxO Raw was most tempting simply because I did not need a whole processing suite as I was already using Lightroom. In the end, I’m glad I didn’t place that order, as Lightroom has come through – in spades.

Lightroom does it again!

In the most recent Lightroom update, 12.3 (also for Adobe Camera Raw), Adobe introduced AI DeNoise. Anyone who has even the slightest concern about noise can now sleep easy as the quality of the images using this new technology is stunningly good. Furthermore, there is absolutely no need for any other noise reduction software. Right-click on an image, choose Enhance > DeNoise, and 40 seconds later (at least on my MacBookPro), I have a DNG file that exudes realistic de-noised smoothness while maintaining pinpoint sharpness in all the right places.

Although ISO 3200 poses no real noise problem in screen viewing and for prints,

it cleans up beautifully, smoothly, and naturally with Lightroom’s new AI Denoise enhancement.

I’ve always believed in Lightroom and have often wondered why photographers used other apps in addition to LR. I realize “different strokes for different folks”, but to often it seems, people think more is better. For my purposes at least, there is no other photo processing app on the market allows me to:

- catalogue my tens of thousands of image and call up any one or group of images so quickly, by keyword, date, camera, lens, location, etc.

- process each image or batch of images, with key adjustments of Auto Black Point and Auto White Point along with highly tailored Shadow and Highlight adjustments, plus Exposure, Contrast, Texture, Clarity, Dehaze, etc. In fact, I have re-processed raw files and jpegs from 20+ years ago using today’s much updated processing engine, and have seen marked improvement to what I had thought was a pretty darn good photograph;

- create beautifully toned black-and-white images, just like I was back in the darkroom, but with much greater precisions and repeatability;

- create highly detailed masks and graduated masks for accurately shaping the lighting of photographs, and adjusting sharpness and colour balance, amongst other edits;

- remove unwanted and unsightly details using spot healing and cloning;

- synchronise my images and setting with both my iPad and iPhone Lightroom Mobile apps;

- export each image or batch of images in virtually any size or dimensions needed. Along with LR/Mogrify 2, it’s easy to add borders, text, additional watermarks, etc. all at the click of a button;

- print each image or batch of images to exacting sizes, dimensions, and standards with or without borders/margins, watermarks and text notes;

- create books from within the app to ensure optimal sizing of photographs;

- save every size, dimension, development process, etc., etc., etc., as a pre-set for repeatable exactness. This has been wonderful for processing, printing and exporting, but also for any repetitive task including managing EXIF and IPTC data.

This really was not meant to be an advertisement for Lightroom Classic or Mobile. After all, this blog started life as an examination of noise in the OM-1. However, with the additional of AI Denoise, it shows Adobe is working behind the scenes to improve their app and stay competitive, even if they are a bit late to the party. Thanks Adobe.

OM-1 w/100-400mm ƒ5.0-6.3; ƒ6.3 @ 1/1250; ISO 800; EV-⅔

With last year’s addition of the incredibly helpful AI Masking features and now the DeNoise function, there really is no reason for me to consider shopping around for something better. It can’t be found! Yes, that means I continue to pay the monthly subscription costs for my Adobe Photography suite, but in balance, I think it is now paying off more than ever before.

Don’t take my word for it. Consider watching these videos or reading the article for more info:

- Tomas Eisl video: OM System OM-1 – Image Noise Expert Guide and In-Depth Knowledge

- Joseph Ellis video: Printing big from Micro Four Thirds

- Eric Chan article (from th Lightroom guru himself): Noise Demystified

Thanks for reading!

If you have any questions or comments about small sensor photography, OM Systems, noise or anything else, please add it to the Comments section below.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email so you are instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Photo Club at Workshops.