Beautiful Autumn Light . . .

631 words; 6 photographs; 3-minute read

. . . at least here in /southern Ontario. Not to boast, but we’ve been enjoying 20°C to 28°C days and brilliantly clear blue skies without a cloud in site. What’s not to like?

I’m dedicating this blog post to my dear wife, life partner and best friend. Two months ago, she underwent a hip replacement and this weekend, successfully hiked 10km over our two hikes. I’m amazed, and she is ecstatic. Her recovery is on-going, but getting better everyday. I know how grateful she is to her health care professionals at St. Mike’s and her physiotherapists, but it also comes down to her own determination!

Now for some Autumn Light . . .

OM-1 | M. Zuiko ED 8-25mm ƒ4 at 23mm (46mm efov) | ƒ5.6 @ 1/2000 and 1/32000 | HDR blend +/– EV2 | Lightroom

I’m of two minds regarding this gorgeous weather. It’s easy to fall into the trap of celebrating—who doesn’t love a warm October day?—but it is also a stark reminder that being 10°C above normal has its costs as well: everywhere is dry; it may be confusing wildlife, birds and insects; and it’s the product of our lifestyle and the carbon we continue to spew into our air.

OM-1 | 25mm | ƒ 5.6 @ 1/125 | ISO 800 | Lightroom

In other words, enjoy it now, but it’s all connected to the wildfires, the smoke, the shorter ski season, the increased frequency and severity of storms and flooding and droughts. There’s no such thing as a free lunch, right!?

The photos in this post are from the last couple of days out and about. We chose late in the day more for the cooler temps than for the light, but, hey, I’ll take the gorgeous late-day warm, angled light anytime. And when the sunsets and the forest becomes dark, well, that’s what ISO 3200 is for.

OM-1 | 25mm (50mm efov) | POL| ƒ5.6 @ 1/13 | ISO 3200 | Lightroom

I specifically went out with only the M. Zuiko Digital ED 8-25mm ƒ4 PRO zoom (16-50mm efov). I love this lens. It is so versatile. I can get ‘close’ if I need to, but really it’s the premier landscape lens. It’s sharp wide open and is brilliant at ƒ5.6 or even ƒ8.

OM-1 | 8mm (16mm efov) | ƒ5.6 @ 1/80 and 1/1250 | HDR +/– EV2 | Lightroom

With the bright autumn light slanting through the forests, I often shot using HDR. Lightroom Desktop (not Mobile!!) has an excellent HDR Blend mode that uses only 2 files: the brightest and the darkest. I typically shoot 3 frames EV2 apart giving me a 2 over and 2 under. But I also shot 3 frames, EV3 apart for 3 over and 3 under. Both worked brilliantly, but +/– EV2 covered the dynamic range well.

OM-1 | 25mm (50mm efov) | ƒ5.6 @ 1/10 and 1/160 | HDR blend +/– EV2 | Lightroom

You’ll notice that every photo presented here but one, relies on back and side-lighting. Front lighting is, frankly, boring, too ‘tectbook’ with little character. AS I walk along, I’m constantly assessing the interplay of light and details.

When I stop to compose, I’m composing the light as much as I’m composing for leading lines and three-dimensionality of the foreground, mid-ground and background relationships. It’s the light that counts; how it shapes the land, the textures and the colours.

OM-1 | 15mm (30mm efov) | ƒ5.6 @ 1/40 and 1/2500 | HDR blend +/– EV3 | Lightroom

Thanks for reading. Be sure to get out and spend some time enjoying the beauty autumn has in store for us.

Be sure to SHARE and COMMENT, and, if you’re not yet a subscriber the SUBSCRIBE—it’s as easy as adding your email. And, no, I do not ever share or sell emails. Nor will I hound you with posts.

BOLO! Upcoming Presentations

522 words; 4 photos; 3-minute read

Next week I have two evening presentations lined up:

- Monday 15 Sept., Hamilton Camera Club, “Just Photography” — an exploration of the grey area between authentic photography and digital art. At what point does the use of third-party editing and Generative AI turn your photographs into digital art?

- Wednesday 17 Sept., Guelph Photographers Guild, “iPhoneography”—how great photographs can be made with phone camera

Just Photography—Pure & Natural

As I wrote in an earlier blog post (Navigating the AI Juggernaut), there is no escaping AI these days. Along with Third-Party Pre-Sets, the two technologies are speeding up the editing process while providing unlimited creative freedom. But, are AI and Pre-Sets also eroding the authenticity of photography?

If it is not acceptable to judge AI images and photographs in the same competition, how much AI or Third-party editing should be permitted?

It seems everyone and every photo app company has jumped on the AI bandwagon creating this unspoken expectation that we accept and adopt these push-button editing solutions because they will make our life easier. I’m asking the question, should we?

What might be ideal for commercial photography is playing havoc with competition photography. And what about decorative photography—to what extent are AI-users willing to divulge to clients their use of AI and Third-Party pre-sets in making a photograph they claim to be ‘theirs’?

28mm | ƒ5 @ 1/80 | ISO 100 | Lightroom | #AuthenticPhotography (made without the use of third-party pre-sets or Generative AI)

With blue hour and golden hour pre-sets, generative fill, expand and replace, at what point does the photograph stop being a photograph and become digital art? Can digital art be called photography? Is it possible to carve out a space for Authentic Photography? What, exactly, is Authentic Photography?

Many photographers are grappling with these questions everyday. The blurred lines created by these advances represent the grey areas we will be exploring on Monday evening with the Hamilton Camera Club.

iPhoneography

The ubiquitous phone camera. With us everyday and every waking moment of our 21st century existence. Though we often treat them as such, they are far beyond the Instamatics of last century. Are we really taking full advantage of the cutting-edge technology sitting in our pocket or purse?

iPhone 8 Plus — the camera that’s always with me.

Like you, I shoot with a ‘real’ camera. But my camera and sensor agnosticism has led me to explore and unlock some of the potential built into phone cameras. I’ve learned that the versatility of phone cameras, despite the limitations of sensor size and lenses, can result in some truly remarkable photographs. Especially when, as Ansel Adams once said, “the most important component of a camera is the twelve inches behind it.”

Join me Wednesday evening with the Guelph Photographers Guild for what I hope is an inspiring presentation unlocking the true potential of the ubiquitous phone camera.

iPhone 11 Pro | 6mm (50mm efov) | ƒ2 @ 1/950 | ISO 20

Looking forward to meeting you next week!

The subscription plot thickens

Topaz Labs enters the subscription fray.

681 words; 4 photographs; 3-minute read

As a ‘founding customer’, I received an email today from TopazLabs, stating that they will be moving to a subscription model. If you use Topaz, you may have received the same email. I was assured that my current desktop version of PhotoAI would remain valid in perpetuity with the standard caveat of free updates being available for up to 1 year after purchase.

So, in some ways, things haven’t changed: buy PhotoAI desktop for USD $199 and use it forever with 1 year of upgrades. Renewals are USD $119 unless you choose to auto-renew which is discounted to USD $99/year.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro )120mm efov) | ƒ8 @ 1/125 | ISO 200 | Lightroom

All of this is confirmed on TopazLabs website. However, a little digging turned up some interesting reading.

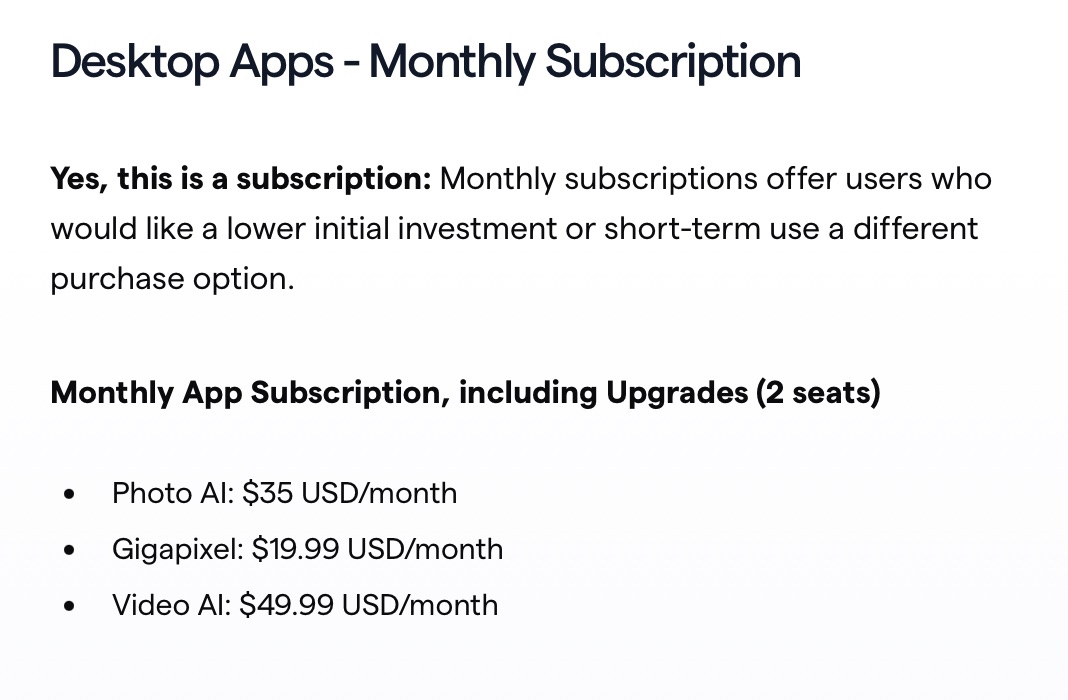

A Monthly Subscription has been introduced for each of their desktop apps (PhotoAI, Gigapixel and VideoAI). Photo AI will be USD $35/month. I choked when I saw the price. Why so much? For 12 months, it would be $420!! I just rechecked the website and, sure enough, it really is $35/month. And that does not include additional ‘Cloud Credits’ for faster AI processing.

Huh? What am I missing here? Why would someone pay $420 each year for software that is $200 + $100/year thereafter?

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/80 | ISO 1600| 10-shot in-camera Focus Stack | Lightroom

Currently, I’m paying CAD $16/month (USD $12/mo) for Lightroom Mobile and desktop + Lightroom Classic + 1 TB of Adobe cloud space. It’s easy to forget that this subscription also comes with the highly useful Lightroom Camera for iPhone (with hdr-raw capture), Adobe fonts and a highly customizable Adobe Portfolio website—the platform I use for luxBorealis.com. Adding industry-leading Photoshop (mobile and desktop) puts the monthly cost up to CAD $26/month (USD $20/mo).

You can do the math as well as I can—$35 for PhotoAI versus $20 for Lightroom + Photoshop. It’s a no-brainer. To be fair, Topaz offers WebTools, a series of apps that are similar to, though not as complete as the various desktop modules in PhotoAI, (denoise, sharpen, upscale, etc.). But even they are, collectively, $20/month for an annual commitment of $200. Even Capture One, as industry-leading as Lightroom, is USD $25/month. What’s with TopazLabs?

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/100 | ISO 1600 | Lightroom

Earlier this year, I did a fairly detailed direct comparison of Topaz with Lightroom and DxO: how well could each demosaic, denoise and sharpen raw files? I found the three were almost indistinguishable. So, in my eyes, it seems more than a bit unreasonable for Topaz Labs to be charging as much as they are for software that may match Lightroom in basic image quality, but lacks the complexity and depth of Lightroom as an almost complete editing suite.

Anyway . . . I’m still shaking my head.

On a related note . . . Earlier this week I was approached by DxO HQ in France to evaluate DxO PhotoLab 9. They assured me that it would remain a standalone app and would not be transitioning to a subscription model. I figure it will take me a few weeks to put together a thorough review in the context of someone who is well-entrenched in Lightroom—so stay tuned!

OM-1 | 23mm (46mm efov) + POL| ƒ5.6 @ 1/500 | ISO 200 | HHHR | Lightroom

My hope is that DxO has come through with an editing suite that will be a solid standalone competitor for Lightroom, along the lines of Capture One, if only to make the switch away from subscriptions closer to reality. Interesting, last week Fstoppers had an article The End of Adobe’s Monopoly? Why Creatives Are Switching which has generated much discussion. Perhaps with Topaz’s pricing challenges and a new DxO PhotoLab 9, we may be one step closer to ditching subscriptions.

Thanks for reading! Add your COMMENTS below or your questions. Hit the SUBSCRIBE button to receive notice of each post and be sure to SHARE this with others.

A Week in Killarney Provincial Park—2.4 billion years in the making

1114 words; 14 photographs; 6 minutes

For the past week, I’ve had the pleasure and honour of being the Friends of Killarney Park Artist in Residence.

Killarney Provincial Park is truly a gem in the crown of Ontario Parks. From a landscape photographer’s perspective, the unique juxtaposition of the pink granite of the Killarney batholith and the white quartzite La Cloche Range mean more than simply colourful rocks. The two rock types are crucial in determining the biology going on at the surface as well.

Scale, perspective, juxtaposition, and timing make this the quintessential view of Killarney Provincial Park: billion-year-old pink granite backed by 2.4 billion-year-old white quartzite.

OM-1 | 100mm (200mm efov) | POL | ƒ5.6 @ 1/125 | ISO 200 | Lightroom

This week, I was overwhelmed by the variety of colourful fungus/mushroom species on display along all of the trails. Rain from the previous week must have triggered them as many were new emergents. My 60mm Macro lens teamed up with in-camera focus-stacking were essential for capturing the depth necessary for clear, crisp photographs.

At just 3cm high, this diminutive mushroom was right in my campsite.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/60 | ISO 200 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

These long, slender mushrooms, found along the campground road, were just 4 to 5cm in height.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/6 | ISO 200 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

Found in the deep shade along the trail to A.Y. Jackson Lake.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ5.6 @ 1/60 | ISO 200 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

I found these unique fungi along the Lake of the Woods Trail and the Cranberry Bog Trail.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/50 | ISO 1600 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

Aside from determining the names of the different mushroom, the difficulty with mushrooms is that they are at ground level. Despite having a ground sheet, my knees and elbows took a beating. Then, keeping still for 10 consecutive exposures while crouched on all fours isn’t easy! For some, I improvised, resting my hands and the camera on my waist pack camera bag, using it like a bean bag on the ground for support. I’m sure people passing by had a good laugh at this old man with his butt in the air looking at mushrooms!

Using a tripod was certainly an option, but, in the summer heat, I was feeling lazy and didn’t feel like lugging it around with me. Once again, I was pleasantly surprised, shocked even, at how well the internal stabilization of the OM-1 worked. I realize now that I could have (should have) bumped the ISO up for focus stacking to at least 400 if not 800.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/25 | ISO 200 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

Landscapes lagged behind somewhat. In the early part of the week, we were plagued with high temperatures and humidity, turning the blue skies milky, rather than filling them with fair-weather cumulus. Smoke from western wildfires also contributed to the haziness.

OM-1 | 8-25mm at 10mm (20mm efov) | POL | ƒ5.6 @ 1/250 | ISO 200 | HHHR | Lightroom

From a workshop perspective, things were slow at the beginning of the week. However, after my slide presentation Wednesday evening—Ontario’s Natural Gems: Nature photography in our own backyards— attendance picked up for the Thursday and Friday programmes. We had a great range of abilities—from beginners to seasoned photographers—and cameras—phones, point and shoots, DSLRS and mirrorless—and ages—from under 10 to over 70. The best part was everyone was patient, inquisitive and wanting to put into practice new techniques and new ways of seeing.

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/125 | ISO 800 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

I presented each ‘Walk, Talk & Shoot” as an outing dedicated to sketching. Our goal was not to make masterpieces, but rather to discover and make photographic sketches of how light creates shape, texture and colour, and how perspective changes from standing to crouching to putting the camera right down on the ground for a worm’s eye view; how vertical can be made horizontal or even square, and how to zoom using your feet to get closer and closer and closer. I related how I came to this idea of sketching after viewing a sketch book of renowned artist Robert Bateman, during a presentation of his many years ago; it has stuck with me since.

OM-1 | 12-100mm at 28mm (56mm efov) | ƒ5.6 @ 1/40 | ISO 200 | Lightroom

OM-1 | 8-25mm at 9mm (18mm efov) | POL | ƒ8 @ 1/320 | ISO 800 | HHHR | Lightroom

We worked on techniques for phone cameras, as well; for example, rotating the phone upside down to place the camera right at ground level; switching on the Rule of Thirds grid; and using Live Photos set to Long Exposure to capture moving water.

I find it impossible to visit the north and not photograph these unique plants. (Yes, they are plants, not a fungus!)

OM-1 | 60mm Macro (120mm efov) | ƒ4 @ 1/30 | ISO 200 | 10x in-camera focus stack | Lightroom

The added value of the Artist in Residence programme is that it also gives each artist plenty of time on their own to explore the park and their art. I pre-hiked each of the trails my programmes were using, plus I got out to a new trail to me, Lake of the Woods, off the Bell Lake Road.

I also returned to a couple of favourite places: a late evening dash down the Chikanishing River Trail to catch the sun over the water, as well as an evening spent paying homage to A.Y. Jackson at his namesake lake and nearby Lake Sheguiandah, whose cliffs come alive in the late day sun.

OM-1 | 8-25mm at 9mm (18mm efov) | POL | ƒ11 @ 1/125 | ISO 200 | HHHR | Lightroom

OM-1 w/ 12-100mm at 80mm (160mm efov) | POL | ƒ5.6 @ 1/80 | ISO 400 | Lightroom

Many thanks to Ontario Parks staff and the Friends of Killarney staff for a great week in Killarney Provincial Park and for your helpful insights and guidance. I’d name each of you, but I’m afraid of leaving out one or two, so suffice it to say, each of you made meaningful contributions, for which I am grateful.

OM-1 | 8-25mm at 8mm (16mm efov) | POL | ƒ8 @ 1/2500 | ISO 800 | HHHR | Lightroom

Thanks for reading! Be sure to add to the discussion with a question or COMMENT about equipment, techniques or locations.

Killarney! Artist in Residence

As of Monday 28 July, I’ll be taking up my post as Artist in Residence for a week at Killarney Provincial Park in Ontario. Organized by the Friends of Killarney Park, I am thrilled and honoured to be their first photographer in the programme.

24mm | ƒ11@30sec | ISO 100 | Lightroom

Killarney is one of Ontario’s true gems of a provincial park. It is classic Canadian Shield: ancient rock billions of years old, hundreds of lakes and rivers with a mix of rocky outcrops and hills covered in northern Great Lakes mixed forest, verging on coniferous boreal in places. Killarney began life billions of years ago with what is now the LaCloche range of low white quartzite hills, once the core of mountains higher than Everest is today. A couple of billions years later, the Grenville Orogeny (mountain-building) shoved the pink granite into place along the southern edge of the park, providing the startling contrast of billion-year-old pink granite and 3-billion-year-old white quartzite.

105mm | ƒ 5.6 @ 1/200 | ISO 200 | Lightroom

In the billion years since then, there have multiple and long periods of glaciation which further shaped Killarney: carving deep valleys, polishing the rock smooth in some places and etching the rock in others with chatter marks, deep gouges and smoother scour marks caused by flowing water.

24mm | ƒ11 @ 1/125 | ISO 200 | Lightroom

I’ve visited Killarney a number of times over the decades, twice in the depths of winter. Between the biota and the landscapes, there is always more than enough to keep an outdoor photographer busy. This goes right back to the Group of Seven. A.Y. Jackson along with members of the Ontario Society of Artists lobbied the Ontario government for protection, which was achieved in 1964.

24m | ƒ16 @ 5sec. | ISO 100 | Lightroom

Sadly, some of the lakes still feel the effects of ‘Acid Deposition’ (a.k.a. Acid Rain) from the 1960s and 70s. Emissions from the Sudbury Superstack and coal-fired generating stations wreaked havoc throughout the region. The lakes are perfectly clear and blue due to the lack of biota and fish in the lakes.

35mm | ƒ11 @ 1/160 | ISO 100 | Lightroom

Artist in Residence

Each of the outings (see below) will be an informal “Walk, Talk & Shoot” session. We’ll take advantage of photo ops along the way for instruction and guidance, with a bent towards nature, outdoor and landscape photography. The goal won’t be finishing the trail but rather capturing some engaging photographs. We may go 500m, we may only go 5m—it all depends on what there is to photograph.

The programme is as follows:

- Monday, 10am to Noon: We’ll meet at the Nature Centre and have a look along the Trout Creek Trail + bridge over to start of La Cloche Trail;

- Tuesday, 10am to Noon: We’ll meet at the Main Gate and Walk, Talk & Shoot along the Granite Ridge Trail

- Wednesday, 7pm at the Amphitheater: I’ll be presenting Ontario’s Natural Gems: Nature and Outdoor photography in our backyards—an inspirational look at photographing the beautiful places close to home

- Thursday, 10am to Noon: We’ll meet at Second Beach to discover photographic gems along the Cranberry Bog Trail

- Friday, 10am to Noon: We’ll meet at the Nature Centre and have a look along the Trout Creek Trail + bridge over to start of La Cloche Trail;

Everyone is welcome, though I’m sure there is a sign-up list at the Park Office. On a personal note, I’m greatly looking forward to meeting people who want to take their photography further. Photography is all about seeing, so, whether it’s a phone camera, a DSLR, mirrorless or a point-and-shoot, the best camera is the one that’s with you!

18mm | ƒ4@15sec. | ISO 3200 | Lightroom

I’m also looking forward to discovering Killarney in the summer, from the early morning blue and golden hours, right through to the dead of night. Yes, that includes working on some astrophotography. I’ll be working on both colour and black-and-white photographs, as always, trying to capture the essence of place and the art inherent in nature.

So, join me at Killarney!

Recommended reading:

Killarney GeoTour (OMNRF PDF): I find that the more I know about the place I’m photographing, the more meaningful and informed my photographs are. This an excellent overview of how the landscape of Killarney became what it is today.

Killarney’s Beating Heart: The Park Which Painters Saved: Blog Post by Zac Metcalfe