Photo contests—What to do?

Have you ever entered a photo contest?

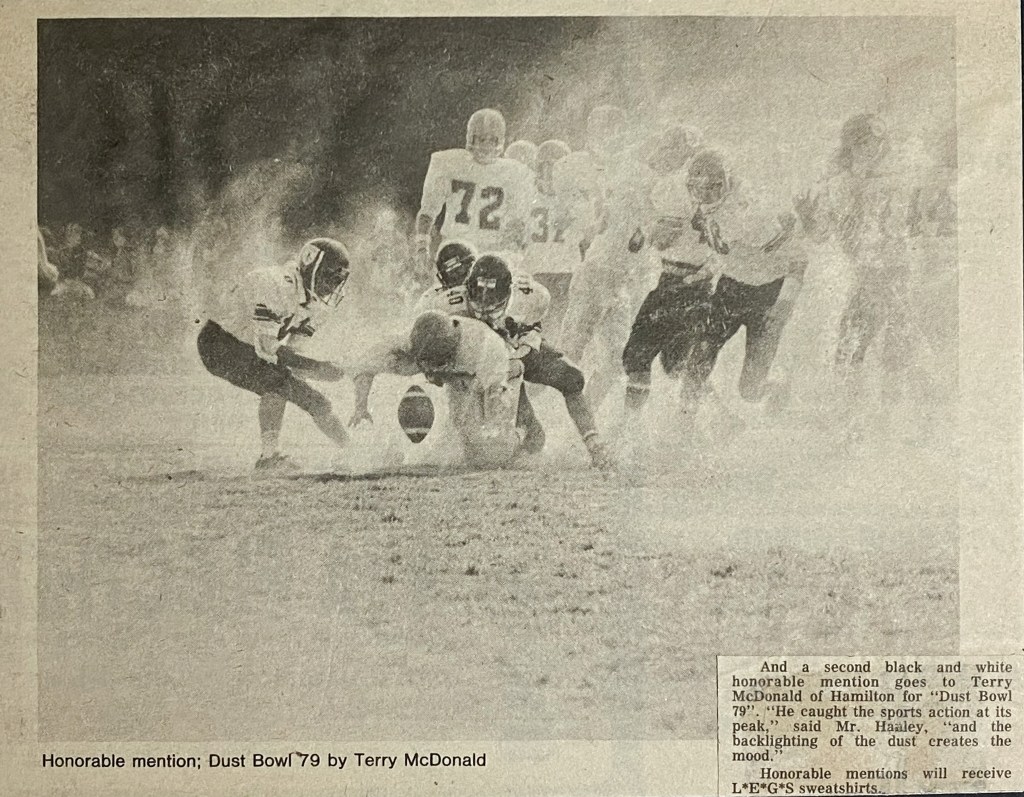

I remember the first time I entered one. It was 1980 and the Hamilton Spectator was running the contest. I was in high school and I entered a shot I took during a football game. The quarterback had fumbled the ball and it was silhouetted in the dust between him and the ground with lots of players gathering around. A classic and one I was so proud of. I was thrilled when I received an honourable mention. It was a shot very early in my photo career and one that I had worked hard to get—no motor drive, no burst, just good timing, and a bit of luck! I was positively ebullient until I saw that the winning photo was taken with a 110 Instamatic. How depressing, but it certainly got me thinking about photo contests, judges and photography in general.

For various reasons, it is hard to predict just how contests will end up. Sometimes, the judges have a preconceived notion of what they want. Or, they’ve been specifically instructed to look for specific types of photos that will fit the needs of the organization running the contest. And then there is simply the volume of great photos entered—it becomes a crap shoot. But this article isn’t meant to dissect ‘how to win’, but rather ‘should you enter?’.

A few contests I’ve come across lately are structured around charitable organizations looking to add to their photo collection (see the list at the bottom). That, in itself, is not a bad thing, but photographers really should be aware of exactly what they are entering and how their photos will be used. CHECK THE FINE PRINT. The other thing to consider is that entering a photo contest is a bit like entering a lottery. The judges will quickly separate the wheat from the chaff, but they will typically be left with a lot of wheat—perhaps hundreds of high quality, dramatic, well-executed photographs—but only a handful of prizes. There are a number of reasons for this:

- Cameras are so good nowadays with accurate AF and AE so, often, JPEGs are usable right out of the camera;

- More photographers have more disposable income to spend on mega-lenses and cameras. Remember, it’s not pros buying the bulk of the pro cameras and glass, it is dedicated and wealthy amateurs.

- There are far more options for processing photos, especially ones using push-buttons and AI corrections that once took minutes to hours to achieve;

- People seem to have more discretionary time to spend to obtain great photos; and

- People are much more widely travelled than 20 or more years ago, so there is easily an order of magnitude more of high quality images to choose from.

So, it’s not unusual for organizations to run contests, especially charitable organizations that are trying to stretch their charitable donations further. And this is where you come in . . . We all have dozens, hundreds, maybe even thousands of excellent photos. And with digital photography, we often have multiple copies of that same photo that are all similar. My question to you is, what are you going to do with them?

If you sell prints or canvases of your photos, great. You will have an active market of willing buyers and you may be earning some good money from your prints. If you put images up on stock photography sites, you may be earning some revenue from them, but typically, nature, landscape and wildlife photography doesn’t pay well, mostly because there is so much of it out there. My guess is, the majority of your images are not earning anything and are taking up space on your hard drive.

Which ever scenario fits your photography, you will have images that may well be valuable to a charitable organization. They can either sit on your hard drive or you can contribute them to help a cause that is important to you. No, you will not receive a tax receipt and no, you may not even win the photo contest. In fact, the images you contribute may never be used, but at least you’ve made an attempt to help.

I’ve read a number of blog posts that specifically direct photographers to “never enter photo contests as they steal your images and you never get paid for them”. This is completely false. The organization does not steal your images. Once you enter your images, you are typically agreeing to the organization using your images for their own communications, media and educational uses in perpetuity. You retain the copyright, but they are permitted to use the images you submit, whether you win or not.

One interpretation I’ve seen related to this is “if your images are good enough to win a photo contest, then they are good enough to earn you some cash”. Well, this may be true, and certainly prize winning images are top notch. But ‘earning cash’ from photography is not that simple. Photographers earn money through direct sales of prints or digital downloads or through stock agencies or by freelancing their time and work. Typically, the first two do not pay well unless you have dedicated yourself to the business of photography. You see photography in and of itself is not a business. And posting your images on the web, on Instagram or Flickr or an Adobe Portfolio site or another website, might get you a few hits and a few sales, but to really earn money, you need to be (a) shooting for specific uses; (b) making your photos easily downloadable for stock use; and (c) marketing your photographs to the people and organizations who want to buy them. All of that takes a lot of dedicated time.

Another way of looking at it is this: If you approach photography like you approach, for example, golf, you may go out for a morning or an evening of shooting somewhere special and capture some great images. But, like golf, you are doing it as a past time, a hobby, something to provide you with personal rewards and pleasure. Nothing wrong with this at all. In fact, it takes the pressure off of always having to perform. It’s pure enjoyment.

So, now you have a collection of photographs that are somewhat unique and of better-than-average quality, but you are not marketing them specifically. Who markets their golf game other than the pros? You are the ideal person to enter photo contests and the charitable organizations running them will love you for it.

A couple of things to be aware of. Most contest will clearly say something to the effect that:

- “copyright remains with the photographer”: This is great as the image remains your property. As owner, you might even be able to sell it on as a print. Bottom line: you maintain the rights over the image.

- “photographers will receive credit for their work”: In fact they may even have a specific place where you indicate how you would like to be credited; e.g. photography by Terry A. McDonald – luxBorealis.com;

- “the organization will retain the right to use your photographs in perpetuity”: It sounds like forever (and, technically, it is) but the reality is, images go stale if they are overused. What this really means is they don’t need to keep track of which images “expire” when. It makes it a lot easier for the organization and typically, they won’t keep using the same images year after year as their marketing begins to look tired.

Now, if you find that you keep winning contest after contest, then you really do need to re-consider your priorities and, perhaps, put a push on stock photography or direct sales or possibly freelance work for magazines and other users of photography. But don’t go putting the cart before the horse. Many photographers don’t enter contest (a) because they don’t feel they’ll win; and (b) because they don’t want to give away their images for free.

My suggestion is to consider the benefits to the organization you are supporting by entering the photos. Nature and outdoor organizations can use all they help they can get and your photos might just help them achieve their goals, the same goals that may have brought you to the organization in the first place.

One word of warning . . . There are a number of prestigious photo contests around the world that have a long history of attracting only the absolute best in nature and wildlife photography. The most obvious example of this the Wildlife Photographer of the Year, run by the British Museum of Natural History. It is the one that is exhibited at the ROM each year. Needless to say, it would be a feather in your cap if you placed in this contest. HOWEVER, there are a number of contests that may appear equally prestigious, but don’t seem to have the backing of any established organization, other than their own. Be wary of these types of contests. I sometimes wonder (a) how legit are they?; and (b) do they actually come though with what they claim?

Again, before entering, do your homework: READ THE FINE PRINT. Get to know the organization you are supporting by entering the contest. Start small and work your way up, unless, of course, you have made that one amazingly phenomenal image that would win just about anything. We all have those images (😊), it’s just a matter of sharing them with the world around us.

Good luck! And drop me a comment to tell us how things went or if you are entering.

Thanks for reading!

If you have any comments, questions, experiences or suggestions about photo contests or any of the organizations listed here, please add them to the Comments section. I also appreciate it when you share my blog post with other photographers or within your camera club.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email up at the top to be instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

You can view my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com. Consider booking a PhotoTalks presentation or workshop for your Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.

Here are a few contests to consider:

- Nature Canada 2024 Photo Contest

- Bruce Trail Conservancy Magazine Photo Contest 2024

- BirdsCanada 2025 Calendar Call for Photos

- Nature Conservancy of Canada Small Acts of Nature Photo Contest 2024

- Canadian Geographic Wildlife Photography of the Year 2024

- Lake Biodiversity Photo Challenge 2024

Kodak Photo CDs—OMG!

Hands up if you have negatives or slides from the last century scanned to Kodak Photo CDs. Hands up if you even know what a Photo CD is. How about negatives? Slides?

Right. I’m talking ancient history to some of you—the pre-digital era. But that’s okay. Read and learn about the hazards of legacy file formats by manufacturers and processes that no longer exist!

I was heavily invested in film photography from the mid-1970s right through to the early 2000s and have thousands of 35mm slides, 6×7 and 4×5 transparencies. However, back then, I took advantage of slide scanning tech offered by Kodak (who? you ask!!), to preserve my slides forever as digital files. So I have about 300 of my best slides from then, scanned to 3 Kodak Photo CDs. The trouble now is I can’t ‘read’ them. Neither my current MacOS nor Photoshop2024 can read PCD files. The Photo CD disk could be read by the Finder, but nothing I tried would open the file and, over the years, I’ve developed a few tricks and workarounds for file formats. Nothing I tried worked! Yikes!

Needless to say, this started a hunt for some way to convert all those ‘great’ slides to a format that could be read. Enter GraphicConverter. I had totally forgotten about this app—one that I used extensively at the beginning of the computer era—for manipulating images and saving to different file formats. It is still around, in version 12, and guess what? It works!!!

It’s nice that GraphicConverter is a shareware app. You can buy it directly from the Apple App Store, but even better is downloading from the provider, Lemcke Software, to try it first. If it works for you, then you can pay them. No obligation and no up front payment information—just download and go.

I really like the way I can batch convert either through the drag-and-drop option (pictured) or through the usual interface. I can also select from a number of different file formats for saving (though DNG is not supported), and I can easily specific which folder to save it to. In ten minutes I had 94 PCD files converted to PSD and added to Lightroom CC.

The only downside is that the new Denoise AI technology is not compatible with PSD files (not yet, anyway). Nor will it work on JPEGs or TIFFs, only raw files. But that’s only a mild set-back. BTW, I saved to PSD file format as it was almost half the size of a TIFF (19mb vs 34mb). I would never convert to a JPEG as I would lose too much important data for post-processing, which is definitely needed for these files.

GraphicConverter is far more powerful and has far more options than I will ever need. However, it solved the problem I had of converting Kodak Photo CD PCD files to something I can work with, like Photoshop (PSD) files. Furthermore, GraphicConverter works with Apple Silicon Macs (i.e. with ‘M-series’ chips) and, more importantly, it does a very good job of keeping whatever highlight information is encoded in the scan. Other file conversion apps do not, so be wary of alternatives. Note that is you have an older Mac, you can download GraphicConverter 10.

THIS—the Finder window on the left—became THAT—the photo I was hoping to open and work with in Lightroom.

Success! Now, if only I had sprung for the extra resolution on the Kodak Photo CD. They offered a ’64-base’ 4096 × 6144 file size. The file size of these are the standard 16-base, 2048px by 3072px, or about 6mp. But, back in the early 2000s this was plenty big enough. In fact, it was larger than professional digital SLRs at the time—the Nikon D1 was just 2.7mb!! With cropping of the slide mount edge it works out to about 2000×3000, just large enough for a 7×10″ or thereabouts.

Thanks for reading!

If you have any comments questions or suggestions about file conversion, Kodak Photo CDs, PCDs, DNGs or PSDs, please add them to the Comments section. I also appreciate it anytime you can share my blog post with other photographers or within your camera club.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email up at the top to be instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a PhotoTalks presentation or workshop for your Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.

Field and Screen is live!

One of the most common questions I’ve received during workshops and PhotoTalk presentations is, “How did you get from ‘there’ to ‘here’?”, ‘there’ being the scene captured in the field, and ‘here’ being the finished image or print. Field and Screen is an attempt to bridge that gap.

I’m a sworn Real-world photographer. What you see displayed in my photographs are representations of my experiences in the field. They is not SOOC images—the raw file is processed to breathe life back into what I call ‘machine files’, bringing the human emotion to bear in re-creating the experiences of ‘being there’.

To do this takes effort. Field & Screen walks you through the process of assembling the aesthetic elements of the scene, given the ambient conditions present at the time. Technical considerations are discussed, followed by post-capture processing techniques, specifically using Lightroom.

Have a look at the first instalment: Clearing Storm, Bow River, Banff:

Thanks for reading. Be sure to leave a comment or ask a question, and most importantly, share this with another photographer or your photos club.

Excellent article from Tom Stirr

Tom Stirr is the man behind smallsensorphotography.com. In his latest blog post entitled, Investment Choices, he thoughtfully outlines a number of factors that photographers and photo-enthusiasts could/should consider prior to making equipment purchases.

He makes some very good points regarding sensor size, dynamic range, AI software and the many options available in computational photography that may supersede the old adage of ‘bigger is better’.

In particular, if people are really honest with themselves and their true needs as photographers, a 20MP camera system is likely the ideal sensor size—the sweet spot—and putting those 20MP onto a smaller sensor makes even more sense with the subsequent gain in image stabilization and focal length along with a reduction in gear weight.

Food for thought.

I encourage you to have a look at Tom’s article before your next gear purchase.

OM-1 w/ 12-100 ƒ4 @23mm (46mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1sec, handheld; ISO 3200

Raw image processed in Lightroom Classic

A photograph like this would have been impossible in the film days without a tripod and very challenging even today without superb sensor stabilization and post-process AI noise reduction.

OM System 2x Digital Teleconverter – How good is it?

Since I began using the OM system OM-1, I’ve been intrigued by the 2x Digital Teleconverter (2xDTC). It is one of the camera’s computational photography options and is easily accessed via the menus (2.2 Other Shooting Functions). When the camera is set to LSF+Raw (Large Super Fine JPEG + a Raw file), you get two files, both at the native resolution of 3188×5184 pixels: the original raw at the native focal length plus a JPEG produced from the cropped raw that is then re-sized and enhanced to be double the focal length.

Left: the original Raw image; Right: the resulting 2xDTC JPEG produced in-camera.

OM-1 w/M.Zuiko Digital 100-400mm ƒ5-6.3 @ 400mm (evoke 800mm); ƒ8 @ 1/2500; ISO 800, handheld, which is the same shooting style I would use for this kind of photograph.

The 2xDTC image has an efov of 1600mm, with no loss of light!

I’ve read a number of posts and watched a few YouTube videos about the 2xDTC process and the jury seems to be out as to how useful it is. This post is meant to set the record straight.

The advantage is you get double the focal length without buying or having to carry an extra accessory and with no loss of light. A real teleconverter fits between the camera and the lens and magnifies 2x, but the downside is it reduces the light by 2 stops; ƒ5.6 @ 1/2000sec shutter speed suddenly becomes ƒ5.6 @ 1/500, potentially reducing the sharpness of the image when handholding long focal lengths. As with everything in photography, it’s a trade off; double the focal length but 1/4 the light. By the way, by all accounts, Olympus teleconverters are beautifully matched to the lenses that accept them, maintaining excellent image sharpness, but at a loss of 2 stops.

The 2xDTC doubles the focal length with no loss of light, but does the image quality hold up?

In this YouTube video professional British wildlife photographer Andy Rouse calls the 2xDTC ”a hidden gem” and says ”the results are quite actually amazing”. He feels that the quality from the JPEG is better than the quality from the raw file cropped then re-sized to the same size as the JPEG. In fact, he goes as far as saying the files are good enough for the stock agency he’s with. He recognises the shortcomings with regards to sharpness, but overall gives it a thumbs up.

Peter Forsgård, finds the 2xDTC ”helpful sometimes” as he explains in this YouTube video. However, unlike Andy Rouse, Peter Forsgård found that a cropped raw is better than the JPEG produced using the 2xDTC.

At the same time, Thomas Stirr at SmallSensorPhotography.com has some excellent out-of-the-camera JPEGs made using the 100-400 and the 2xDTC.

So what to do? How does the 2xDTC stack up?

Full Disclosure: Without even looking at the images, I must declare my bias against JPEGs. I’ve always disliked the fact that JPEGs are finished products. They’ve been processed, sharpened, and compressed by the camera. Call me a control freak, but the individual photographer can do little to further improve the base image quality (detail, sharpness, highlights, shadows) without stressing the file quality. Whereas with Raw, much can be done to improve the image beyond what a camera can do in creating a JPEG.

Warning: Pixel-peeping ahead. Since moving from full frame to Micro Four Thirds, I’ve come to realize there is little to be gained from continually pixel peeping every image, mainly because the people looking at photos and buying photos do not pixel peep. Other photographers pixel peep, but they don’t generally buy other photographers photos. People who love a photo are drawn in by the emotional connection with the photograph, not the sensor it’s made with. Yes, the image must be well-crafted with sharp focus and accurate exposure. And certainly tweaking the colour balance and shaping the light using masking all play a role, but people who like the photo do not stick their noses up against the photo to check out the pixels.

So why am I pixel peeping now? I’m assessing the file in terms of fine prints, not casual web scrolling. Rather than incurring the hefty cost of printing each of the test shots, I’ll look at them on-screen at 100%. Basically, I’m trying to answer two fundamental questions:

- Would the JPEG created by the Digital Teleconverter stand up to the requirements of a fine print made at native resolution, basically a 12 x16″ image that would print nicely on 13 x 19′ fine art paper? This kind of quality would also be acceptable for photo competitions and stock agencies.

- Is it possible to improve upon the JPEG by using a crop from the original raw file and properly sharpening and enlarging it?

I examined the images at 100% after making JPEGs of each the test images. Wait! JPEGs? Why JPEGs? Like it or not, JPEGs are the online currency of photographs. Once a raw image has been processed, it gets output as a JPEG for online print services and for stock agencies. Sometimes finished Raw files are output as TIFF files, but the file size is often 20 to 30 times larger; e.g. a 4.2mb JPEG versus a 121mb TIFF.

Needless to say, I wasn’t entirely enamoured with the in-camera JPEG made by the Digital Teleconverter. Comparison photos are shown below. The cropped and enlarged Raw file is worse – just as Andy Rouse said, so it will need a bit of work.

Right: The original Raw file cropped to the same image view, then resized to the same native resolution as the JPEG.

The Raw file is clearly mushy, but the JPEG isn’t really “better”. It’s sharper, especially in the feather detail of the breast, but around the head, it looks more like a paint-by-numbers picture. Neither is usable for a fine art print.

However, the question becomes, would the Raw file come out better if it was sharpened before or after enlarging? Here are two images – you tell me . . .

Lightroom > Detail: Sharpening=40; Radius=1.0; Detail=50; Masking=50

Right: Sharpening is applied AFTER resizing back to native resolution.

Lightroom > Detail: Sharpening=100; Radius=1.3; Detail=50; Masking=70.

To get this file even close to other, much more aggressive sharpening was required.

Perhaps like you, I’m not happy with the quality of either image. The ‘sharpening before’ image looks crisper, but there are artefacts and a real graininess to the image. The ‘sharpening after’ is just plain mushy. To be clear, I did not sharpen each image the same, as that would be unrealistic. Each photo was sharpened to achieve my subjective ‘ideal’ sharpness. I specifically tried to improve feather detail beyond what the original JPEG showed.

But I think there is more that can be done to the Raw file to improved it. One of the most important options would be to run it through Lightroom’s AI-powered Denoise. This is a recent feature that was not available to Andy Rouse or Peter Forsgård when they did their testing.

Can AI Denoise improve the Raw file?

In a word: YES! Big time! Have a look at these comparison images:

Lightroom > Detail: Sharpening=40; Radius=1.0; Detail=50; Masking=50

Right: A Denoise setting of 80 nicely cleaned this file, after which appropriate sharpening was applied.

Lightroom > Detail: Sharpening=60; Radius=1.0; Detail=50; Masking=50

The big difference between the original raw and the denoised version is how clean the smooth-textured areas are.Take a look at the eye, an important part of every wildlife photo. It is much cleaner after denoising. Also, compare the large feathers of the wing. The denoised feathers are gorgeous!

Overall, the detail is about the same. Check the really fine short feathery bits sticking out at the back of the neck and at the top of the back. The detail is the same, but the clarity of the surrounding background allows those details to stand out more clearly. As well, with the denoised image, there isn’t the distracting graininess through the neck and breast feathers.

But how does the the denoised, sharpened and resized raw compare to the original in-camera JPEG?

Right: The denoised, sharpened and resized Raw file.

The difference is clear!

So now we know the difference is clear. A better image can be made by denoising, sharpening and resizing the original Raw file. This is why I declared my bias against JPEGs early in the article! But, is the improvement great enough to make the added time and effort worth it? It depends:

- Do you have the time?

It only takes two minutes to Denoise, sharpen and crop, provided you have the app . . . - Do you have Lightroom Classic?

Denoise is only available in Lr Classic (Desktop), not LrMobile or LrWeb (yet!). Topaz Denoise and DxO PureRaw also have excellent AI denoise options. - Do you need a native resolution image file?

The cropped Raw would be 1944 x 2592 pixels – large enough for any web use and will provide a high quality 5×7 print; even an 8×10 is possible or an 11×14 canvas – all without upsizing. - Will you be printing the image or submitting it for competition or to a stock agency?

If it’s for web use, projection or small prints, the in-camera JPEG will do. Otherwise, the two minutes are well worth it.

Everything about the Denoised, sharpened and resized Raw file is superior to the in-camera JPEG. The Denoised-and-Sharpened Raw is sharper with fewer and smaller ‘paint-by-number’ areas. Overall, I feel it has a much more three-dimensional look with more realistic colours. It just looks more realistic.

So I think we’ve put to rest the Digital Teleconverter question. Bottom line: If you are after ultimate image quality, do not use it! That being said, I have two more comparisons to show you . . .

Once the original files are downsized, the differences become much less apparent. The above example is sized to print an 8×10″ fine print; i.e. at 300 pixels per inch. Other than the slight difference in colour balance and some mid-tone contrast (both of which are easily corrected in Lightroom), the difference in overall sharpness is minimal, though, the Denoised-and-Sharpened Raw file would still print better, as it retains the three-dimensionality referred to above.

However, when these same images are resized to 1600 pixels for web use (see below), the difference in apparent sharpness disappears completely, though still the Denoised-and-Sharpened Raw file has a presence to it not found in the JPEG (and that may vary with different subjects and scenes).

Final Verdict

In summary, the 2xDTC is a convenient way to double the focal length of any lens. The is especially true for those who regularly shoot JPEGS and are not interested in post-capture processing. My advice to you, though, is to set the file option to LSF+Raw as this will give you your JPEG but it will also save a Raw file, thereby future-proofing your work in case you take up processing at a later date.

The 2xDTC can be helpful when travelling, as it double the range of a ‘walkabout’ lens, such as the 12-100mm (efov of 24-200mm) without having to carry any extra gear. And, if the longest focal length in your kit is simply not long enough, you now have another option. Andy Rouse claims the quality is good enough for professional uses and I can’t argue with his success. But, to me, JPEGs from 2xDTC seem to lack sharpness, mid-tone contrast and three-dimensionality.

TIt is important to remember that though the 2xDTC does a fair job in a number of circumstances, it does not replace the quality provided by a real teleconverter, which for OM System cameras and lenses is excellent.

Furthermore, before using the 2xDTC, photographers should consider whether a full, native resolution image file is actually needed – which is surprisingly rare. By far the majority of images are used and viewed at considerably smaller sizes (e.g. for web, small prints, etc.) so, a simple crop of the raw file would suffice without using the 2xDTC. And, as shown above, if captured as a Raw file then processed properly, a higher quality image is possible.

The images presented here demonstrate that if you are inclined to capture Raw files and process them in an app like Lightroom Classic, Topaz PhotoAI or DxOPureRaw, it is in your best interest to extract a final photo by denoising, sharpening and (if needed) resizing the raw file. By all means, shoot using 2xDTC – I find it helpful for framing – but capture images using LSF+Raw so you can make the necessary improvements. As mentioned previously, processing takes no more than a couple of minutes and you are welcome to use the settings provided above as starting points. The little bit of time it takes, certainly pays dividends in image quality!

Try it out and let me know how it goes!

Thanks for reading!

If you have any questions or comments about OM System, the Digital Teleconverter option, raw capture, processing in Lightroom or anything else, please add it to the Comments section.

If you are not yet a subscriber, then consider adding your email in the form below to be instantly alerted to new blog posts. And I promise not to inundate your inbox.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Photo Club or a personal field and/or screen workshop at Workshops.