Finding the Sweet Spot in Photography

NOTE: This article first appeared on the Luminous-Landscape.com as a three-part series, beginning with: https://luminous-landscape.com/finding-the-sweet-spot-in-photography-part-1/. The whole of the article is included below.

If you’ve ever played tennis or baseball, then you’ll know what a sweet spot is—the magical power centre of a racquet or bat between ‘best bounce’ and the ‘dead zone’. Finding that sweet spot can make the difference between repeated success or pain and frustration. So too with photography, but over the years, as technology has advanced, that sweet spot has changed with it, creating a new ideal point where image quality, system size and cost meet.

I’m not a working pro, but like many photo enthusiasts, I take my photography very seriously. A few years ago, unhappy with the status quo, I began a quest to find that photographic sweet spot. It was not a quest for perfection as much as finding a camera system that fulfils my demands of landscape, nature, birds & wildlife and travel photography—one that:

→ produces raw files of high enough IQ for publication and fine art prints;

→ can get wet, performs in extreme weather, and at ‘the edge of light’;

→ has fast autofocus, excellent stabilization, sharp lenses, and high ISO detail; and

→ won’t break the bank.

In all, a system that works with me, not against me.

But this defines a lot of systems out there. In fact, I could make a case for any of the systems I’ve used through my photography journey: 35mm film, 6×7, 4×5, 4/3, digital full frame, 1” sensor, even the camera that’s ‘always with us’—the ubiquitous phone camera. Each has performed extremely well for me in a variety of outdoor, indoor, and studio situations.

NOTE: Tap or click on a photo to open it full-screen. Use the back button to return to the blog. Each photo is optimized for 1200px on the longest side. If your device shows it larger, some blurring may be noticeable.

Navigating the trade-offs

Photography is and always has been one trade-off after another. Take landscape photography: a smaller aperture is needed for greater depth of field, but not too small to cause diffraction. Yet, a fast enough shutter speed is needed to stop the motion of foreground grasses or cattails. We’ve all been there, waiting patiently, perhaps for the light, but more often for the @#%$! wind to die down.

On the other hand, birds and wildlife demand long telephotos, tack sharp and well-stabilized, often heavy and costly. For both scenarios, we need a sensor large enough to capture, in low light, fine details in foliage, fur and feathers, but equipment that is not so large and heavy as to make it unwieldy. More trade-offs.

Travel, reportage and documentary photographers want a small, light, portable system with fast lenses, but they don’t want to give up image quality either. Can there possibly be a sweet spot to meet all these demands?

Yes, and surprisingly, it’s been out there all along, hiding in plain sight, gradually evolving, maturing and perfecting its specs. The problem has been that, like many in the field, I’ve had blinders on. Embarrassingly, I began my digital journey with the ideal system but, following the hype, I went down the path most travelled instead. All this time I’ve been looking in the wrong direction. It took a young, open-minded student of mine to get me to remove the blinders and re-consider my roots.

The proof is in the print

Before I get to that sweet spot, I want to share some photographs since, in the end, it’s the results that count. Here are three photographs from a recent trip to Tanzania. I’ve chosen them because each represents one or more limiting factors in photography: fine detail, low-light performance, and smoothness of tone. Other factors contributing to overall performance include ergonomics, weight, and speed or ease of use. However, the costs and benefits of these can only be judged through hands-on experience with the equipment.

Note: All three photographs were made handheld, a testament to modern IBIS.

So, what about those trade-offs?

Would you believe me if I said these were made with an iPhone? No, definitely not. How about a 1” sensor camera. Possibly. A few years ago, I wrote in LuLa about The Ultimate Travel Camera—the Sony RX10iii (now iv), with its excellent ƒ2.4-4 stabilized Zeiss 24-600mm equivalent lens. What about M43s? APS-C? Full frame?

When I shot 4×5, it was because I could not get a decent 16×20” print from 35mm. With recent advances in digital technology, I can now produce a 16×20 from my current system that is of higher visual quality than a 16×20” made, at the time, from a 4×5 negative or transparency. And, I can make that raw file without a tripod from a camera and lens combination weighing less than a quarter of my 4×5 camera and lens.

The high image quality of these files gives pause for thought. I know you want to pixel-peep them, and you may have already started, but they are down-scaled JPEGs for online use, so you don’t get the genuine experience of seeing them ’live’.

But it’s pixel peeping that created the beast we live with and has become a national past-time for photo bloggers around the world. Yet, that’s not how we view photographs. Perhaps it’s time to turn the Holy Grail on its head. If it sounds provocative, it’s meant to be. You can take in one of two ways: either take a moment to think differently, even if it’s just a thought exercise at this stage, or you can remain trapped in the status quo.

Let’s face it, full-frame is the default, though costly option and marketed as the best choice for modern photographers. After all, bigger is better, isn’t it? Why drive a Ford when you can afford a Ferrari?

But perhaps we’re looking at it the wrong way around. If the files produced above are of high enough quality for prints and publication (which they are), then shouldn’t that be the ruler we measure systems against? After all, you don’t need a 20-foot ladder to climb a 10-foot wall. While the 20-foot ladder is bigger, it’s not necessarily better. While you may claim neighbourhood bragging rights for having the longest ladder, it’s overkill and it’s unwieldy.

I ran into this two winters ago when I missed some shots of snowy owls. For me, it was the last straw, after missing other bird shots over the previous year. I was using a 3.3kg (7¼ lbs) FF Nikon camera plus telephoto zoom and it was too unwieldy to acquire focus and shoot in time. My current system with 60% more telephoto reach is only 2kg and half the size.

Confession Time

You’ve probably figured it out by now, but I did not make these photos with my iPhone, nor with a full frame system. They’re from an OM System OM-1 with M.Zuiko lenses. My guess is you are now scrolling back up to those images, scrutinizing them for any tell-tale signs. I’ll admit, they are downsized to 1200px from the originals and shown as JPEGs online, so you don’t get the genuine experience of seeing them ’live’.

But let’s get back to real-world scenarios—when was the last time you made a fine print larger than, say, 13×17”? Typically, photos are never shown larger than 3840×2880 pixels which is an 11MB file, the same width as a 4K TV. In fact, it’s estimated that more than 90% of photos made are never seen beyond a computer screen. Another way of looking at it is this: how may MB have you paid for, but are throwing away each time you downsize a file?

I feel I might be hitting a nerve right now. During presentations, this is when the audience starts to shift uncomfortably in their seats and the defensive posturing begins, usually around the need for extra pixels for cropping. If that’s the case, then M43 is the sweet spot as the effective focal lengths are doubled. So my 100-400mm/5-6.3 zoom provides the equivalent field of view (efov) of a 200-800 full frame lens. My 12-100/4 PRO IS lens is like a 24-200. Tack sharp from one end to the other and corner to corner, it’s the perfect zoom for travel photography. And my landscape lens is an 8-25mm/4 PRO, or 16-50mm in FF terms, another ideal zoom range, unavailable for FF.

All this represents photography’s dirty secret that no one wants to admit to—unless they’ve actually worked with M43: small sensors are now technologically advanced to compete with full frame. The system is mature enough to have a range of high quality optics that don’t break the bank. In one sense, M43 represents a democratization of photography in that we can achieve high IQ without paying the full-frame premium. I could never afford the kind of FF telephoto lens that is producing the wildlife and bird photos I am now able to make. Nor would I want to carry it around.

Back to prints

Many pros claim to make 30×40” fine art prints. They’re big and they’re gorgeous. Can you do that directly from M43 raw file? No, not without up-scaling. But you can’t make them directly from a FF sensor either. Even a 60MP sensor has a maximum direct print size of 21×31”. Are there M43 users making 30×40” and selling them? You bet there are. The bottom line is this: If you make dozens of 20×30” fine art prints (not canvases, as they require less resolution) a year and sell them, then a FF maybe your best option.

But here’s what Pulitzer Prize-winning and National Geographic Photographer Jay Dickson said, ”I have prints hanging in our home, shot with an [M43] Olympus, that are 50” on the long side, and the quality is stunning.” (Link) That was said eight years ago—long before OM System upgraded the sensor for the OM-1 and OM-1 Mark II.

Professional wedding and portrait photographer Joseph Ellis agrees. He regularly makes, “absolutely stunning prints from M43 up to what the Europeans call A1 (about 23”x33”). (Link) In his side-by-side comparison of 30” prints from a 20MP M43 Olympus and 60MP Phase One IQ16030, there was ”no discernible difference at normal viewing distances”. As he described, differences didn’t really show up until they were ”sniffing the prints”.

In one sense, a paradigm shift from full-frame to M43 mirrors that of the shift from large and medium format to the ’compact’ and ’miniature’ 35mm cameras that began to appear over 100 years ago. While not the first 35mm, ”Oskar Barnack had designed the original 35mm Leica back the 1920’s with the design ethic of small, compact, unobtrusive and capable of extremely high quality” says Jay Dickman (Link). Dan O’Neill adds, ”While older photographers avoided Barnack’s invention, the younger crowd embraced it. Leica quickly became popular with the new generation of artists and photojournalists influenced by avant-garde styles like the Bauhaus movement”. (Link) Whether or not M43 gains the same kind of following remains to be seen, but the shift in thought remains the same: smaller, lighter, yet professional in design, build and performance.

Micro 4/3 achieves a number of sweet spots each of which have suffered from a disturbing amount of disinformation on photography websites, eager to monetize by promoting the more popular SoNiCan full-frame and APS cameras.

Effective aperture and shutter speed

Despite the disinformation regarding aperture, depth-of-field and exposure scattered around the web, physics tells us that ƒ8 on a M43 lens has the equivalent depth of field of ƒ16 on a full-frame lens of equivalent field of view (efov), the M43 bonus being a shutter speed 2EV faster. Let’s go back to that landscape: given the same ISO, a M43 exposure of ƒ8 at 1/125 produces the identical result in terms of depth of field and exposure as a full frame shot of ƒ16 at 1/30. To me, having that 2EV faster shutter speed means less time waiting for the @#%$! wind to die down. Combined with industry-leading stabilization (see below), it also allows for more flexibility with hand holding the camera.

Sensor Size

A 20.4MP M43 sensor is 5184×3888 pixels, or 17×13” at 300ppi—large enough to cover a two-page spread in a photo book with full bleed. How many prints larger than that do you make? When I need something larger, I use one of two methods for up-scaling:

(1) Lightroom’s Enhanced Super Resolution after running the base raw file through DxO PureRaw or ON1 No Noise—both with phenomenal results; and (2) Topaz PhotoAI’s upscale. It all depends on the photo. There is also OM System’s native High Res Mode, either handheld for 50MP or on a tripod for 80MP. Both do an excellent job. A third alternative I’ve begun using more often is to lock exposure and shoot multiple photos panoramic style. Three-across gives me a vertical of 5184px with a horizontal of around 7000px for a 17×23” direct print. Another option is to shoot across and down in rows, then Merging them in Lightroom with outstanding results.

Size and weight

To me, this is the elephant in the room. Photographers will jokingly complain about the weight of their FF gear, but still consider the struggle part of the experience. Those days are gone for me. I’ve hiked the remote and rugged Superior Coast trail with 35mm and 4×5 gear, and dragged full-frame gear all around the Galápagos Islands. Working with M43 is so much sweeter!

With full-frame gear, I always needed a backpack, and it was nothing by a pain. I couldn’t switch lenses on the go like I can with a sling or waist bag. A backpack, must be removed and put down somewhere to open it, take out a lens and switch over, or change a battery, or get a filter, etc. Where I work, this is a problem: next to waterfalls, on a beach, in a wetland, along the muddy banks of a river.

My whole OM system fits into a small sling bag. I have the FF equivalent of 16mm to 800mm glass plus a 120/2.8 Macro lens and a 1.4x Teleconverter, all in a small LowePro AW sling along with a POL, a couple of NDs, a spare battery, a lintless cloth, lens cleaning kit, and a couple of granola bars. When flying, it’s my ‘personal bag’—with all my gear—and it weighs about 4.5kg. When I ‘travel light’ with only a LowePro waist bag, I can still have my three zooms covering from 16mm to 800mm: two in the bag and one on the camera on a shoulder harness, with all the same extras. It doesn’t get better than that.

Cropping

Admittedly, there are times when ’zoom with your feet’ isn’t feasible. Take the Cordon-bleu bird above. Tack sharp. I got as close as possible to it and managed a 3888×2916 pixel image—a vertical crop from a horizontal frame. Could I have achieved the same with a full-frame system? Almost. Although the focal length was 400mm, on a M43 sensor, that’s equivalent to 800mm in FF terms. If the same shot was made on a 60MP Sony A7Rv with a 400mm lens, the height of the identical photo would be 3461px (13mm/23.8mm*6336px), a loss of 427 pixels at an additional cost of CAD $3000. With a 47MP Nikon Z8, the image height would be 2994px (894 pixels less) and $4100 more expensive. That’s the FF premium. So, as far as pixels on subject are concerned, the OM-1 has it.

Sensor stabilization

I am neither a physicist nor an engineer, but what I understand from both is that the smaller M43 sensor is far easier and more efficient to stabilize than a full-frame sensor 4 times the size. Therefore, in a less expensive camera, Olympus has achieved extremely effective in-body stabilization, some say industry-leading, especially when paired with in-lens stabilization.

The High ISO Noise Debate

There is no doubt that M43 produces more noise than a full-frame sensor at every ISO. You can see the difference on-screen at 100%. In fact, it was the first thing I noticed with my OM-1 files. However, that’s the trap everyone falls into. Internet pundits love comparing on-screen at 100%, but no one who actually appreciates photographs examines them on-screen like that, only pixel-peeing photographers and internet bloggers do. The reality is, it’s the final photograph that counts, and its emotional appeal. Is grain noticeable in the final photograph? Not for the vast majority of uses, and if the on-screen noise bothers you, cleaning it up is only a few clicks away using DxO PureRaw, ON1 No Noise, Topaz PhotoAI or Lightroom’s Denoise. While I find DxO and ON1 the best of the lot, any one of them cleans the image up beautifully. Voilà, no noise. (More on raw file optimization in an upcoming article).

BTW, the lion shot up above was shot at ISO3200 and you can see every fine hair, even before it was cleaned up. Raw optimization just made it sing.

What about Dynamic Range?

M43 sensors have less dynamic range than FF sensors. There is no doubt. The most recent data from DxOMark measures the DR of the older Olympus OM-D E-M1 Mark II at 12.8, two EV lower than the class-leading Nikon 850 at 14.8. When a scene’s brightness is too great for any sensor to handle, photographers use exposure blending to compensate, to ensure detail is captured in both the shadow and highlight areas. With my OM-1, I keep HDR controls in my customized ’My Menu’, and use them about as often as I do with my D800E (DR of 14.3), which is rarely.

Why not APS? Isn’t that the sweet spot?

APS seems like a good option, but is it really? For me, there are too many trade-offs. If you already have a full-frame system of lenses, then you might think an APS body is the way to go, but you’re not saving any weight or bulk. The savings comes in matching an APS body with lenses designed for it. While lighter-weight APS bodies and lenses certainly have very good functionality at a low price, they have two inherent problems. One: APS bodies and lenses are cheaper for a reason. They are simply not built as ruggedly as an OM-1 or FF, and they often have only one memory card slot along with those shortcomings. Secondly, APS lenses tend to be slower and lack the corner-to-corner and full zoom range sharpness and professional finishing of both FF and M.Zuiko lenses.

To me, the sweet spot lies in creating engaging, high IQ photographs with equipment rugged enough to perform under any circumstances. A system that captures grand landscapes with dramatic light, minute details on a forest floor lit only by tree-hued softness, fleeting birds and wildlife—in any weather, at any time of day, even after the sun’s gone down. A system that will travel with me, provide a range of high quality optics from ultra-wide to telephoto, all in a small package. Funny, how similar the thinking was behind the ’miniature’ Leica 35mm camera. A hundred years on, are we on the brink of another sea change in photography or is the ‘bigger is better’ mantra still too entrenched?

What’s in your future?

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions about OM System and the quality it produces or the photos shown above, be sure to add a comment.

Please SHARE this with other photographers or with your camera club, and consider signing up to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field&Screen workshop at Workshops.

Wildlife and Bird Photography—On Safari in Tanzania, Part 2 – Tarangire National Park

This is Part 2 of a series of posts on our Tanzania trip. Here are links to Part 1 in Arusha National Park (opens in a new tab).

While Arusha National Park is known for its views of Kili, Tarangire is nothing short of quintessential Africa.

It’s the Tarangire River that draws in the wildlife. This is especially true in these dry season months of September to November, when water becomes more and more scare. It’s a gently rolling patchwork of grasses, brown from lack of rain, and still-green acacias dotting the landscape. Baobabs, bare-branched with new flowers and leaves just opening contrast with the leafy-green sausage trees that line river banks, their wares hanging down like a traditional delicatessen.

Olympus/OM System OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko w/ M.Zuiko Digital ED 12-100mm IS PRO @ 12mm (24mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/400, ISO 800, Hand-held High Res; processed in Lightroom

—❦—

Technical note about the photos: Unless otherwise noted, all photos were made with an Olympus/OM System OM-1 with an M.Zuiko Digital ED 100-400/5.0-6.3 IS zoom. Raw files were processed in Lightroom for iPad during the trip with subsequent processing afterwards, as well. Any alterations from this are stated in the captions.

Viewing photos: Click on a photo to view a larger version. Use the back button to return to the blog. The size of each photo is limited to 1500 pixels on the long size. If it appears full-screen, then your device may be up-sizing it, which can lead to blurriness.

—❦—

Strolling through the grasses and amongst the trees are a host of Africa’s finest wildlife: elephants, giraffes, Cape buffalo, waterbuck, impalas, antelope, zebras, wildebeest, dik-diks, and eland amongst others—always with lions, cheetah, leopards and jackals awaiting their opportunity partake of the buffet. Soaring overhead are kettles of vultures, auger buzzards, tawny eagles, fish eagles, martial eagles and snowy-white black-winged kites.

400mm (800mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/400, ISO 1600

These ’cute little guys’ were all around the lodge area, drinking from the water dishes kept full by the lodge staff. Dik-diks are the smallest antelopes, only about 35cm at the shoulder or the size of a dog and are usually quite skitterish.

We stayed in the park at Tarangire Safari Lodge, a relaxed, casual tented camp with safari tents arranged along the top of a ridge overlooking the Tarangire River valley. We’ve been fortunate to travel to many truly beautiful locations around the world, but this is, above all, our favourite. It’s a chill place in the heart of wild Africa. The Simonsons have been running the lodge since the mid-1980s and Annette, her son Brendan and their staff are wonderful stewards of this quintessential corner of Africa, balancing the needs of their guests with the fact that wildlife regularly roams through the lodge grounds (and sometimes the lodge, itself—check out their Insta and FB pages!)

But, it’s the captivating and engaging view that really makes TSL such a favourite place to stay. You could choose not to go on a wildlife drive and still see everything! We’ve sat for hours on the terrace or, during the heat of the day in the open-air lounge, enjoying the unobstructed 270° view—a living diorama of herds of elephants and zebras and waterbuck and giraffe and Cape buffalo and- and- and—casually and continuously moving down the valley slopes to the river, into and across the river, then up the other side.

While reading a book or editing images, a sudden movement down in the valley catches our eye: a young elephant is running, scampering in its trunk-flopping, comical way, towards the water and play time. Just as Arusha National Park is known for its giraffe (Giraffic Park), Tarangire is known for its elephants, though Pachyderm Park, doesn’t have quite the same cachet. The real excitement comes when someone announces that there are elephants on the lodge grounds.

Elephants regularly pass along the back of the tents, browsing on the acacias and sometimes trying to access the water. In fact, we watched as they turned on faucets with their trunks to access water. More on that in Part 3!

iPhone 11 Pro, 2x camera

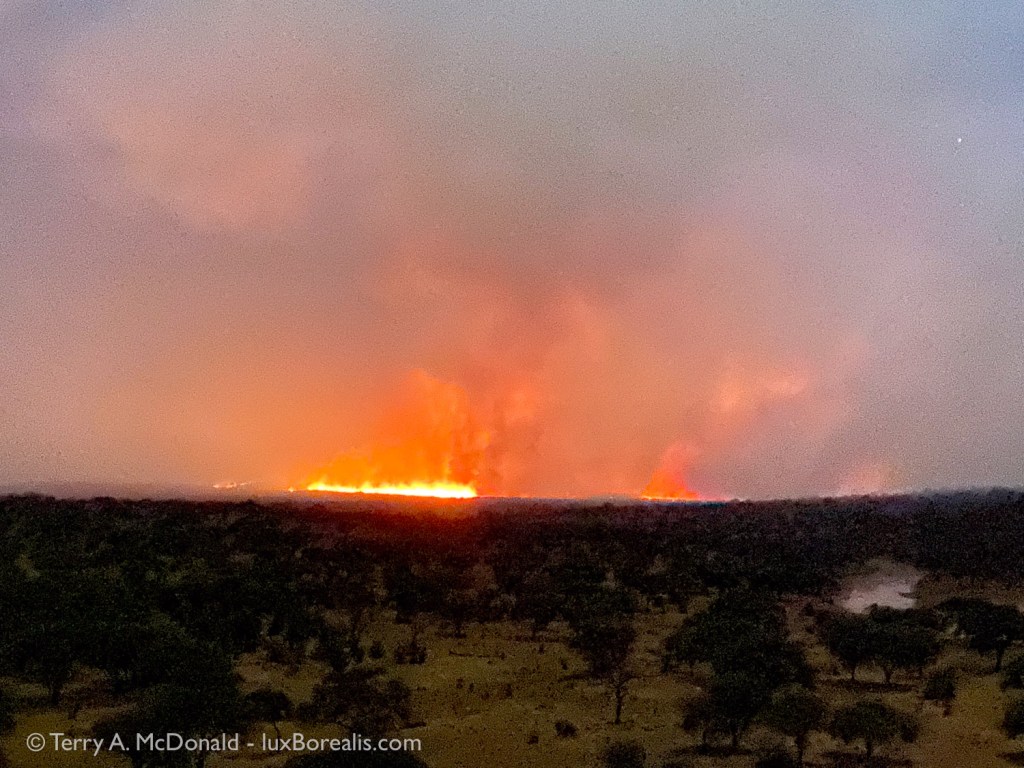

One of the realities of Africa is that famers still use fire to burn crop residues to fertilise the next crop. This fire got out of control and entered the park, burning grasses but not trees, contributing significant air pollution and tiny black cinders of burnt grass that covered everything. The subsequent bonus was that it drove the antelopes, zebras and wildebeest northwards, followed by lions, of course.

One other advantage of being at the lodge is Brenden—the guy in charge. In his young thirties, he has literally grown up there. After his dad passed a few years ago, Brenden stepped in to keep things running with his mom, Annette. Brenden is a knowledgeable birder and accomplished photographer (see @brenden_simonson on Insta) and offers bird hikes from the lodge. Walking through the bush with an armed ranger is an adventure not to be missed. Because Brenden is there all the time, he knows exactly what birds can be found where.

Furthermore, Brenden has put a few large agricultural disks as bird baths out in various places around the lodge and has instructed the staff to keep them clean and filled with water. This alone is all the birds need to congregate around the site. The one outside the dining room provides endless entertainment with parrots and go-away birds competing for time at the bath. The one he’s placed down at the far end also attracts wildlife. We were woken up late on night by the loud sound of lapping, like a dog drinking from its dish. Under the light of the full moon, I kid you not, there was a full-grown leopard, 3-metres from our tent drinking its fill. The next night it returned. The night after that four water buck drank the disk dry. Phenomenal!! If only I could shoot through the mesh of the tent netting.

400mm (800mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/60, ISO 3200

Despite its nondescript colouring, this bird is, hands down, the most interesting animal in Africa. Look at its scientific name. Now, look at its common name. This bird has formed a symbiotic relationship with humans—one of only a few animals to do so—classic mutualism. It finds nesting bees, uses a specific call to signal to traditional foragers like the Hadza people of Tanzania, then guides them to the bees where the Hadzabe enjoy the honey and the honeyguide enjoys the eggs, larvae and beeswax. This may also be the only example of co-evolution between an animal species and humans, that doesn’t involve domestication. Truly fascinating!! I was thrilled to see one and photograph it.

Okay—enough about the lodge, though I could wax on about it forever.

Just like Arusha National Park, Tarangire is full of surprises. However, once you get to know the park, you learn where to look, and the river is biggest draw. After crossing the bridge about 1km south of the lodge, we headed south taking each of the River Loops A, B and C. Where loop B meets the river there is an elephant mud hole. They’re not there everyday, but if the timing is right, like it was for us, you are treated to the happiest, most joyous hour of watching elephants of all ages flipping and flopping in the mud and splashing and spraying themselves with mud and water. Pictures and words don’t begin to describe the experience of pure fun and joy the elephants are having, trumpeting and calling to each other. Even my poor attempt at a 10-minute video doesn’t do it justice.

138mm (276mm efov); ƒ16 @ 1/400, ISO 800

First one family arrived—the youngest literally running towards the mud—then a second family followed. They waited patiently for at least half an hour while the first elephants wallowed and splashed and sprayed and dusted themselves and scratched their sides and bums against a very large boulder. After their time at the spa, the second family did the very same.

Further down, in Loop C, we forded the river, passable during the dry season as the water is only axle-deep. After crossing we could have gone further south, down to the Silale Swamp, but decided to wind our way back to the lodge, slowly meandering north along the east side of the river. Earlier, we had spotted a number of safari trucks stopped in one location—a good indication of something interesting. Sure enough, there were six lions resting and sleeping on the sand beside the river.

269mm (538mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/2000; ISO 1600

Right: 560mm (1120mm efov) w/ MC-14 teleconverter; ƒ11 @ 1/1600, ISO 1600

Oh to have the life of a lion. Sleep all day, periodically keeping an eye out for dinner, then attack, eat and sleep. If only it were that easy, say the lions!

We carried on up to the Matete Picnic Site high above the river, where we found resident and habituated Vervet monkeys with young. Years ago, long before the picnic site was formally developed into what it is now, we encountered mating lions, who just continued on doing their thing as we pulled up near them and watched and listened. Unforgettable really, in so many ways! This time, it was the intimate portraits of these monkeys and their young that made the stop so captivating.

Sometimes we approach this same road by turning south just before the bridge, driving down the east side of the river. This is often where elephants are tracking down to the river along with zebras and wildebeest. Lions are also around, frequenting the ridges and humps in the ground, keeping a watchful eye on what’s happening below. We’ve seen zebra kill along here on a few occasions.

A third favourite location is along the river to the north and west of the lodge. Though we didn’t get there this time, it proved to be a most exciting place when our daughter joined us two weeks later for our second safari to Tarangire. Because she is less interested in birds, Laura and I tried to pack as many birding moments into this safari as we could.

On another drive, we drifted north and eastwards then south to the open country in the hope of seeing a cheetah. No go, but it was still a worthwhile exploration, turning up a black-winged kite, beautiful lilac-breasted rollers, huge ground hornbills, some antelope, zebras, wildebeest, and eland. We also came across large areas burned by the bush fires. At one point, the road was heading directly into a bush fire, but we joined up with the main road which allowed us to head north again, back to the lodge.

It is always with sad hearts that we leave Tarangire Safari Lodge and the National Park. There is nothing that can replace those few days of casual and exciting wildlife viewing combined with chilling on the terrace or in the lounge, never knowing what might suddenly appear, but always knowing there will be something amazing.

Stay tuned to Part 3: Close Encounters with Lions!

If you have any questions about safaris, gear, processing or the photos, add a comment below.

Please take a moment to share this post with other photographers or travellers, armchair or otherwise.

Also, consider signing up to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Subscribe below or scroll up to the top right.

Visit luxBorealis.com for more photos, to order fine art prints and ArtCards, book a Field & Screen workshop, or inquire about an evening PhotoTalk for your nature or camera club.

While casually working away writing and editing, this ‘fellow’ showed up with much hoopla amongst the staff. I wanted to watch and photograph the snake; they just wanted to shuffle it out of the lounge ASAP. But they were very accommodating, waiting until I had the shot I wanted before carefully scooping it up in a bucket and taking it outside.

Adobe Subscription Changes

Just an FYI—Adobe has re-aligned their subscription packages, and it may be in your favour.

Up until yesterday, I was paying CAD $25.99/month for Lightroom CC, Lightroom Classic and Photoshop. To me, this isn’t a great use of my resources as I almost never use Photoshop and almost never for photographs, mostly for creating graphics. The problem was, to get both Lightroom CC and Classic, you needed the $25.99/month place, which included Photoshop.

The only time I need a Photoshop-like product for a photographs is when merging images for HDR, focus stacking or panoramic and only when working on iPad (as Lr for iPad does not!!), so it’s not too common. When travelling with iPad and I want to Merge, I’ve begun using Serif Affinity Photo. Works perfectly!

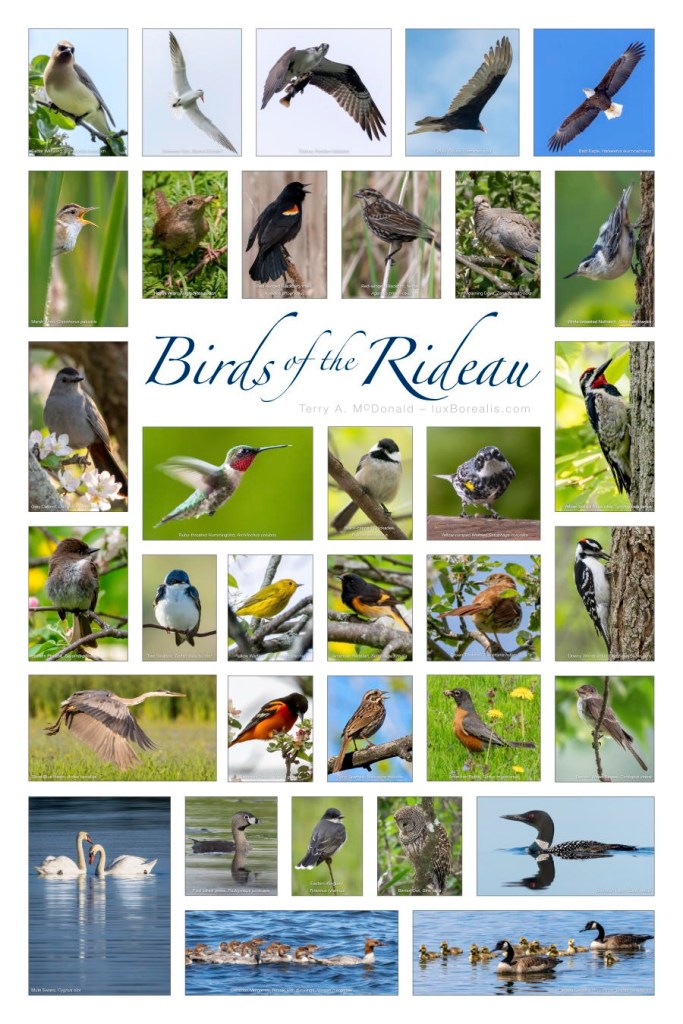

Over the past year or so, I’ve been transitioning to using Serif Affinity products. Originally, I purchased Affinity Publisher to create the large ‘Birds of the Rideau’ poster. But buying their three products together was such a bargain that I purchased Photo and Designer as well.

So, there I am, paying $10/month for Photoshop and hardly using it.

Back in December, I picked up on a mention of Adobe re-aligning plans and it seems to have worked out in my favour. Up to now, if you wanted Lightroom Classic (which is still my legacy photo editor), you were required to subscribe to the higher-priced monthly plan that included Photoshop.

Now, at CAD $15.99/month, we get Lightroom CC and Lightroom Classic. Hooray!! And it still comes with 1TB of online storage. I like working on iPad, so having files available online is very convenient. Surprise, surprise, it also comes with the mobile version of Photoshop, certainly not equal to the laptop/desktop version, but it’s there if I need it.

———

UPDATE – 23 Jan ‘25: I just switched from 15.99/mo monthly payment to an annual payment of $155.88, which is $12.99/month. Easy peasy and was done using the virtual assistant.

———

The switchover was as easy as going to Adobe.com, signing in have a look around. It seems everytime I go back to the Adobe site, the layout has changed. Look for ‘Plans and Proiducts’ and/or ‘Change your plan’.

While my recent files (last 18 months or so) are in the Adobe cloud, my legacy files are all backed up on a hard drive. I’m gradually moving the more used files into the cloud. Having files available anytime, anywhere, without having to cart a hard drive along is certainly convenient.

With all my recent raw files in the cloud, I can work on iPad or laptop anywhere I have a connection. And, if no connection exists, I keep working on Smart Previews and everything gets updated when I next connect.

So, have a look at what plan you’re using. Do you have Photoshop? If you make good use of it, great. But if you’re paying for it, like I did, to get the 1TB Lr CC + Lr Classic plan, have a re-think. You may end up saving yourself $10/month with the new re-aligned plans.

Every little bit helps!

Just 12

American photographer Ansel Adams once said,

“Twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop.”

How was your crop from this past year?

If you’re not familiar with Ansel Adams, he worked through the middle 60 years of the 20th century making spectacular black-and-white photographs of national parks and natural areas in California, mostly with large format cameras. His best-known works were very large black and white prints, handmade from negatives of 4”x5”, to 8”x10”. In his early days, he would trek through Yosemite National Park, summer and winter, carrying a dozen or so glass plates at a time. Even with the switch to sheet film, he still had to carry each pair of sheets in large film holder that was inserted into the camera back, one shot at a time.

Sold via Christie’s (14¾ x 19”) in 2016 for USD47,500. A larger 38×60”, hand-made black-and-white print once hung above the Adams’s fireplace.

This is all to say Adams never had the convenience of auto exposure, burst photography, bracketing, or HDR exposures. Nor did he have zooms. His three ’walkabout’ lenses, included a 90mm wide angle of (around 27mm equivalent), a 150mm ‘normal lens’ (50mm efov) and a 210mm short telephoto in the 65mm range or perhaps a 300mm (108mm efov). It was not only the camera, lenses and backs that were encumbering, his work also required a heavy wooden tripod and black-out cloth.

It is said that good art is the product of limitations—Ansel Adams is certainly a testament to that. For more on how constraints stimulate thinking, read this from verybigbrain.com. Even the great film-maker Orson Welles is known to have said:

“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.”

Therefore, given the limitations Ansel Adams faced, making 12 significant photos in one year was an achievement, though he regularly made even more. For a moment, consider putting yourself in a similar situation, going out for a weekend of serious photography to an amazingly beautiful natural or wilderness area with only three lenses, a tripod and, say 24 exposures. The effort you put into each exposure would be significant and you sure wouldn’t waste any on bracketing!

This photo is the successful product of learning a new technique: hand held focus stacking with my telephoto zoom lens.

Olympus OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 100-400mm at 227mm (554mm efov); ƒ6 @ 1/1600, ISO 800; stacked JPEG processed in Lightroom

So what’s my point here?

I encourage you to look back over the photographs you made in the past year and try to distill the best of your best down to 12 different images. Only 12. Not 13 or 15 or 20. Just 12.

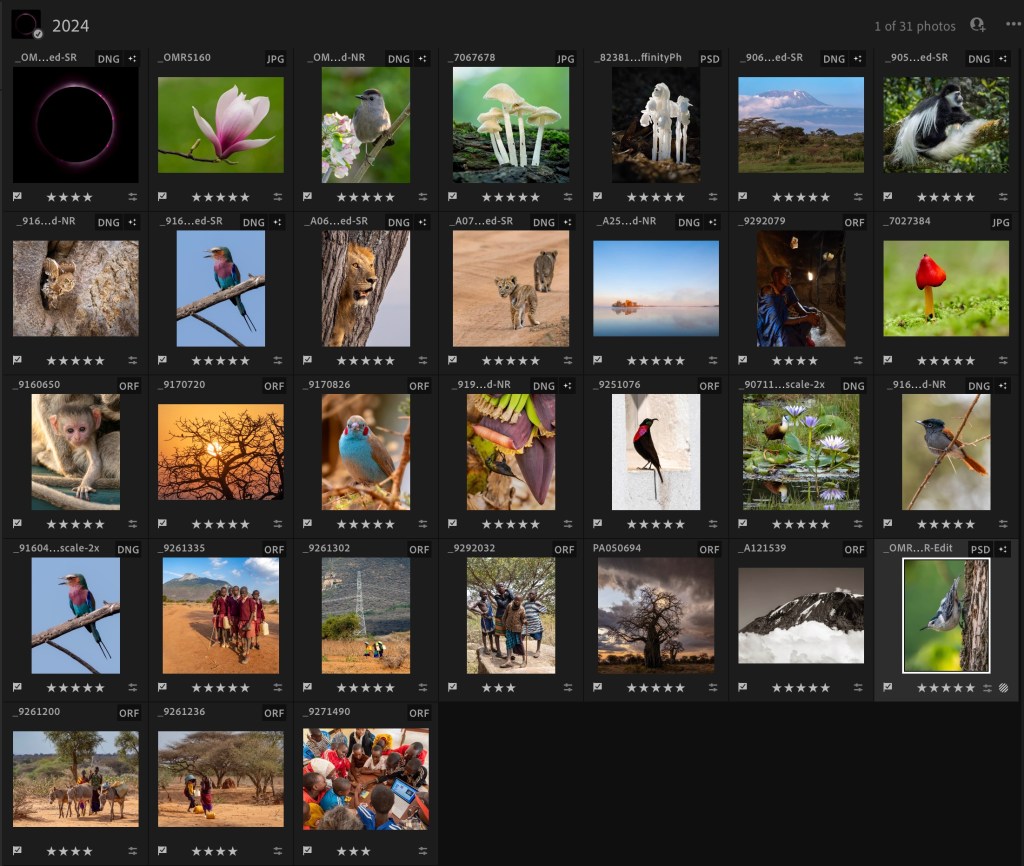

When I take on this task, as I do each year, I break down the year into a series of ‘sessions’, ‘scenes’ or ‘subjects’. I may get two or three top-tier images from one particularly engaging moment or session, so in this exercise, I include only one image from any one scene or session. I just went through my 2024s and came up with 31 (see photo). Now the real work begins!

Looking back over the year in photographs is a healthy exercise for several reasons. First of all, you might be surprised by the number of really good photographs you’ve taken. Hopefully, you won’t be disappointed if they number less than 12—and, if so, ask yourself why? Was it one of those years when family and/or work commitments limited your time spent photographing. If that’s the case, consider building photography into more of a routine in the coming year.

Another image captured with handheld focus stacking, this time with a macro lens.

OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 60mm ƒ2.8 Macro lens; ƒ5.6 @ 1/500, ISO 800; stacked JPEG processed in Lightroom

Do you golf, play hockey or attend a club once a week or take part in another weekly endeavour? Consider trading one of those sessions each month for a few hours out photographing. Try to make it a regular thing, by choosing a series of locations you’d like to visit and going out rain or shine.

Another alternative for increasing the number of photo sessions is to join a local photography club. While they have guest speakers throughout the year, which might provide inspiration, clubs often have field trips, workshops and hands-on learning sessions to broaden your photography. I’ve had people take my workshops for the sole purpose of getting out and photographing.

2024 was the year of the total eclipse here in southern Ontario!

OM-1 w/ 100-400 at 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ16 @ 1/4000, ISO 200 with ND500 + NDx8 filters; raw file processed in DxO RawPrime and Lightroom.

Secondly, looking at a retrospective of the year can give you a sense of where your strengths are, what techniques or styles you enjoy using and, more importantly, what is not working for you. You may have sessions out photographing for which you have no images to consider as your best. Why is that? Was the lighting flat and featureless? Or was there simply nothing compelling to shoot? Perhaps there was something you saw and photographed, but didn’t quite capture what caused you to stop in the first place? These are important developmental questions to consider and are part of the learning journey.

Decades ago, I read an article about Robert Gilka, a long-time Director of Photography at National Geographic. Something written has always stuck with me. He felt there is always a compelling photograph to be captured—it just takes a visionary photographer to see it. Apparently, his test of talent was to give a photographer a roll of black-and-white film, put them in a dark alley, and direct them to come back when they’ve finished the roll. Talk about limitations!

A pair of catbirds frequented the apple tree outside our family cottage, collecting caterpillars and other delicacies to feed their young in the nearby nest. It was just a matter of time before the lighting of early evening (7:20pm) and their perch location was ideal for a photograph.

OM-1 w/100-400mm @ 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/200, ISO 3200; raw file processed in Lightroom.

Ansel Adams often wrote of the value of ’seeing photographs’ even when you’re not photographing. I often see photographs when I’m out driving, but that’s not an entirely safe endeavour. Looking out a window or when out walking, stop and look. Look carefully. In your mind, frame up an interesting pattern or scene. Move forwards, backwards, up and down to compose the photograph. Think through the steps of how you might precisely capture the photograph, what perspective to use, and which focal length would best match that view. It’s a helpful exercise and it doesn’t cost a thing except a moment of your time. In instances like these, once I’ve composed the image, I often take out my phone to make a quick snap.

Choosing photos

If you have plenty of great photographs to choose from, well then that’s a different problem. How do you edit down to just 12? It’s important to look at them, I mean really examine each photograph, closely, looking specifically for flaws. Look at them large, on your TV for example. Check the edges and corners, focus and exposure, horizons, subjects. How is the composition? Rule of Thirds? Foreground, mid-ground and background? An image that initially captures your imagination may in fact have flaws that you first missed because you were taken in by the impact of colours or design or the memory of that significant moment.

There is no right or wrong, and don’t rank them, just choose 12—and learn as you choose. Remember, you’re looking for your 12 best, not 12 perfect photographs. This is especially important if you are new to photography. It’s a learning journey.

Pro Tip: If you are using an editing app like Lightroom, hopefully, throughout the year, you assigned star values to your photos. If not, do so now, at least for the best of the best. This makes selections weeks or months later much easier. Each time I go through a set of images from a photo session, I pick the best by giving them a flag. As I go through them again, I give one star to any worth pursuing with further editing. Once I’ve given a file its first edit, I give it 3 starts. From there, a photograph earns 4 or 5 stars depending on its overall quality and impact.

Once you have your 12 best, consider this—what makes those photographs so successful? To get to the root of your photography, try going beyond ‘location’ or ‘subject’. What ‘worked’ in the photographic sense? Was it the ambience of the time of day or time of year? What about the lighting? The composition? The style? Perhaps all the planets aligned to create a perfect photograph. Drill down to discover: Why? How? As you discover what works, then try to replicate that in future photo sessions.

An adult Pearl-spotted Owlet launches itself from its nest hole in a baobab tree. After seeing the owl with its young in a nearby acacia, and watching the two of them enter the nest, from there, it was a waiting game. Within five minutes, I could see slight movement in the hole, then out flew the adult.

OM-1 w/ 100-400 at 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/800, ISO 1600; raw file processed in Lightroom.

The next 12

Now take a look at the next 12 or 24. Why didn’t they make ‘the cut’? It is just as important to discover what didn’t work, which can provide insights into how you need to improve. Again, don’t consider the location or subject; consider only the photographic elements of composition, lighting, perspective, and editing.

One of my ‘Next 12’. This took some very careful lining up—shifting forward and back, left and rightand finding the ideal focal length—as the sun rose quickly in the morning sky. Hazy smoke from local agricultural burning added the colour.

OM-1 w/ 100-400mm at 210mm (420mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/800, ISO 200; raw file processed in Lightroom.

Take perspective, for example. Not enough is written about ‘where you’re standing and what focal length to use’. Should you have been closer with a wider angle lens to accentuate the foreground? Or should you have been further back with a longer focal length to compress the ‘layers’ of foreground, mid-ground and background?

Fred Picker, the east coast equivalent to Ansel Adams, always felt he had the perfect composition,

“when the scene was looking back at me”.

What an interesting way of looking at perspective and composition. Finding that sweet spot in three-dimensional space is perhaps the most difficult part of photography. Even Ansel Adams recognized,

“A good photograph is knowing where to stand”.

I really am a landscape photographer at heart, though with the addition of a long telephoto zoom, my focus has begun to include birds and wildlife.

OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 12-100mm at 15mm (30mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1/800, ISO 800; Handheld High Resolution; raw file processed in Lightroom.

Whatever you do, DO NOT say or think, ‘If only I had better equipment!’ We all know the adage, ‘a poor carpenter blames his tools’. Just about any camera and lens combination manufactured today—from 1” sensors to Micro 4/3s, APS, and full-frame—will produce sharper photographs and consistently more accurate exposure than any large format equipment Ansel Adams was using.

We really are in the Golden Age of photography. Technology has progressed to provide us with unparalleled image quality, so don’t be too quick to blame your equipment. Learning how to use what you’ve got—camera, lenses, editing app—more effectively and efficiently may be the direction you are headed in this coming year. However, it may be helpful to recognize when you consistently find the need for a wider angle lens or a longer focal length than you have. Too often equipment purchases are based on the whim of ’want’. Looking back at your photos and analyzing them may lead to better insights as to what you would find useful.

At 6:26pm, as the sun set on what was an amazing day of lion-spotting in Tarangire, this male lion got up from its sleep on the sandy river bank to make his presence know to a female lion in the tree above him. Laura manoeuvred the safari truck into just the right position to capture him looking out over the plains.

OM-1 w/ 100-400mm at 300mm (600mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/80, ISO 3200; raw file processed in DxO PureRaw and Lightroom; up-scaled 2x in Lightroom—more on that process in a future blog.

So, now that you have the best of your best photographs, it’s time to make something of them. Two options spring to mind: make a calendar of your 12 best or make a photo book of your 20 best. Most photo books come with 20 pages, so you may as well fill them—but only with your 20 best! Make them full page, with a ½” to 1” white border, so they look like matted photographs. Add a title to the bottom right, something that reminds you of what, where, and when. Don’t try to squeeze in 25 or 30 photos as that will detract from showing your best.

Each year going forward, do the same and watch how you and your photography grow and change. It sounds trite, like school pictures collected by your parents over the years, but it will all make sense and become a point of pride as each year you add another volume to your series.

Good luck, and all the best for a great 2025!

Twelve minutes after sunset—sunset at the Equator is consistently around 6:30pm and is almost instantaneous—and the blue zone is upon us, much faster than here in Canada. Who should show up, but a giraffe. How fortunate!

OM-1 w/ 12-100mm at 100mm (200mm evof); ƒ5.6 @ ⅓ sec., ISO 800; raw file processed in DxO RawPrime and Lightroom.

Note: in this case, Handheld High Res mode could not be used due to the movement of the giraffe. However, the file was successfully up-scaled to 10368×7776 pixels (80.6MP or 34.5” x 26” print) using Lightroom’s Enhanced Super Resolution of the DxO DNG file. More to come on that process in a future blog post!

Wildlife and Bird Photography—On Safari in Tanzania, Part I: Arusha National Park

Kilimanjaro. The very word is evocative.

I don’t know about you, but when I see an image of Mount Kilimanjaro, rising high above the surrounding plains, I begin imagining dramatic adventures, exotic cultures and exciting wildlife encounters in the far-off African savanna. (I also begin humming a tune from Toto, “I bless the rains down in Africa . . . “)

Africa never disappoints, and Tanzania is the gem.

Day 3, 6:48am; M. Zuiko Digital ED 12-100mm ISP PRO @ 86mm (172mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1/200, ISO 200;

The wait was worth it. Seeing Kilimanjaro towering 5km above the surrounding landscape is a spectacular sight at any time of the day. The golden hours of sunrise make it that much sweeter.

Technical note about the photos: Unless otherwise noted, all photos were made with an Olympus OM-1 with an M.Zuiko Digital ED 100-400/5.0-6.3 IS zoom. Raw files were processed in Lightroom for iPad during the trip, with subsequent tweaking from there. Any alterations from this are stated in the captions.

Viewing photos: Click on a photo to view a larger version, then use the back button to return to the blog. The size of each photo is limited to 1500 pixels on the long size. If it appears full-screen, then the device may be upsizing it, which can lead to slight blurriness.

Background

Twenty-four years ago, my wife and I put our teaching careers in Ontario on hold and moved with our 4-year-old daughter to Arusha, Tanzania to teach in an independent school—St. Constantine’s. We chose SCIS because it was not the ‘high-priced expat school’, yet it offered an international educational experience based on the British system, catering to local Tanzanians and UN families from other parts of Africa. Those years are the most memorable of our lives with each and every day truly bringing one adventure after another.

To this day, we are in touch with former students, colleagues and friends, and they were our incentive to return after 20 years. Back in 2007, we had made a short jaunt from England, but this six-week trip would allow us to more fully immerse ourselves back into Tanzanian life and re-connect with the people who meant so much to us. Needless to say, it has been a wonderful homecoming. But I won’t bore you with the human stories and family pics (you can see them on Facebook)—this blog is meant to be about landscape and nature photography.

Minolta DiMage 7i, 80mm (efov), ƒ4 @ 1/1000; jpeg processed in Apple Photos. The Minolta was first digital camera. It offered a 28-200mm lens (efov) and produced excellent 5mp raw files!

Tanzanian National Parks

During our six weeks, we had three trips, ‘safaris’ if you will, to two of our favourite places, Arusha National Park and Tarangire National Park, both of which are close to Arusha. For a few reasons, we decided against going to Ngorongoro Crater and the Serengeti two of the world’s jewels. Having previously visited both, we knew that just about everything we wanted to see could be found in Arusha NP and Tarangire NP, with only one exception, rhinos, but we were okay with that. Furthermore, Ngorongoro Crater itself has a USD $295/day vehicle fee on top of the USD $70/person/day entry permit—over CAD$800 for ONE day! The Serengeti entry fee is USD $70/person/day PLUS the overnight hotel/lodge concession fee of USD $60/person/night, PLUS 18% VAT, PLUS the actual cost of accommodations. Safaris in Tanzania do not come cheaply!! As we were self-driving, our safaris were definitely much less expensive than with a company, but still costly.

Day 2, 9:02am; 100mm (200mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1/5000, ISO 800.

As we returned to the lodge from our morning wildlife drive for breakfast, we were greeted by this herd of Cape buffalo. Needless to say, breakfast had to wait! It is these kinds of opportunities that compel us to stay at accommodations within the National Parks, rather than outside of them.

1/5000 you’re asking? My gear was still set up for birds and distant wildlife—I should have dialled down to ISO 200 as 1/5000 was overkill. Note: I prefer not to use Auto ISO.

BTW, if you’re looking for a safari experience, Tanzania is the destination with four of the world’s most outstanding destinations for landscapes and wildlife: Mt. Kilimanjaro, Ngorongoro Crater, Oldupai Gorge, and the Serengeti, all within a few hours of each other. I can highly recommend three companies:

All are well-run, professional outfits that cater to customized itineraries. If you’re feeling adventurous, Serengeti Select even has a ‘self-drive’ option as well as a beach option at Emayani Lodge on the untouched Indian Ocean coast south of Pangani. Each of the companies can also arrange for tours of the historical and culturally exotic island of Zanzibar and Stone Town. Flights arrive daily to Kilimanjaro International Airport via KLM, Ethiopian Air and Qatar Airways. We chose Ethiopian to reduce costs ($400 cheaper x 2), which was fine, but the leg from Toronto to Addis Ababa is long.

Day 4, 12:10pm; 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ6.3 @ 1/200, ISO 1600; Raw file processed in Lightroom and Topaz Photo AI

The rich cloud forest that wraps around Mount Meru is home to Blue Monkeys and Colobus Monkeys (see below), elephants, Cape buffalo, bushbuck, and a host of other mammal and bird species. Photographing in the deep shade is challenging with shutter speeds slower than ideal when wildlife and the branches they sit on are never still.

Birds and Wildlife

As someone who has studied biology, ecosystems, and geography for most of my life, I am still amazed by the tremendous diversity of plants and animals in East Africa. Where we have a few dozen commonly seen birds in southern Ontario, East Africa has over 100. Tanzania itself boast a bird species list of over 1,000! (Note: Tanzania and Ontario are approximately the same size at about 1 million km2.) While Ontario has a few active predator-prey relationships, the savanna has dozens.

Day 3, 6:56am; 138mm (276mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1/640, ISO 800; Hand-held High Res.

I have to credit this one to our driver-guide, Simbo, who stopped the truck on our way out of the lodge and told me to take this shot. Gladly!

The wealth of large and small mammal and herptile species is truly impressive. More importantly for photographers, much of the wildlife is easily accessible—right outside the car window or even right outside the tent or banda, which is why we prefer staying within the parks! The birds are everywhere, their colourful diversity gracing every garden, but to see the large mammals you really must be in the parks. Both Momella Wildlife Lodge in Arusha National Park and where we stayed in Tarangire—Tarangire Safari Lodge—are both renowned for wildlife that is seen right within the lodge grounds.

Day 2, 5:02pm; 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/160, ISO 1600. Shooting distance was about 1.4m; the 100-400 has amazing close-focus capabilities.

Lizards are fairly common in rocky areas, but to see a snake is uncommon. This one was sunning itself near the road, warming itself in the later afternoon sun. Only a few metres away were two green snakes, which we have yet to identify, actively hunting in the grass.

Bird Photography

Only in the last few years have I developed a keen interest in bird photography, mostly because higher quality, long telephoto lenses have become more affordable. Moving to an Olympus (OMDS OM-1) system last year, along with the M.Zuiko 100-400mmm zoom (200-800mm efov) has made bird photography even more accessible. As I’ve written previously, ergonomics, stabilization, dust/waterproofness, and high ISO quality have been game changers. Paired with the vertical grip with 2nd battery, I was never out of power, even on long days with early morning and evening wildlife drives.

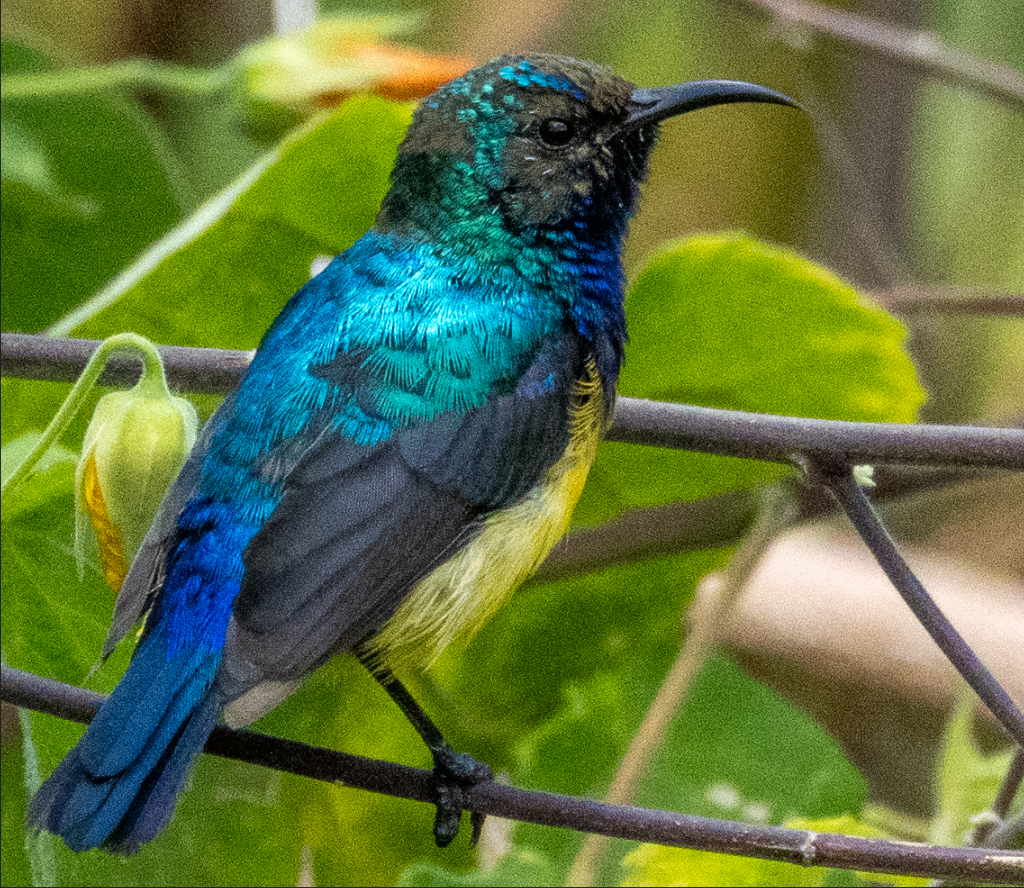

Day 3, 12:54pm; 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/1000, ISO 3200;Lightroom + Topaz Photo AI.

Sunbirds are beautiful, but they tend to do a lot of flitting about. Cloudy skies and dim light under the forest canopy forced me to use ISO 3200. However, Topaz Photo AI cleaned up the noise to provide a beautifully clean image.

Day 3, 3:04pm; 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/800, ISO 1600; Lightroom + Topaz Photo AI. The jacana is a beautiful marsh bird with great, long toes to walk on lily pads, but it would not approach closely. This is a file was a perfect candidate for upsizing in Topaz.

I am also fortunate in that Laura, my better half, has been a keen birder for decades and has an ultra-sensitive eye for spotting birds and wildlife that are otherwise invisible to me. So, we make a good pair. On this safari, we hired a truck and driver-guide, Simbo, but typically, Laura is happy to take the wheel of the safari truck, allowing me to concentrate on photography. For the rest of our stay in Tanzania, we had a truck on loan from our friends in Arusha.

Arusha National Park

Arusha NP is an hour from Arusha and wraps around the eastern flank of Mount Meru, the ‘local volcano’ and Tanzania’s second-highest mountain. In East Africa, proximity to a mountain and higher elevation means greater rainfall, so much of ArushaNP is forested with a range of ecosystems gradually gaining in tree density with rising elevation from its ‘Little Serengeti’ grassland, up to full tropical cloud forest complete with vines, epiphytic plants growing on tree limbs, and trees with huge buttress roots. A diversity of ecosystems means a diversity of wildlife and ArushaNP never disappoints.

Day 2, 7:36am; Olympus OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko Digital ED 12-100mm IS PRO @ 35mm (70mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ ⅓, ISO 200.

Getting up into the forested area was more difficult than we imagined as the road was in dreadful condition (though it looks smooth here!) Even our driver was upset by the lack of maintenance by park officials. However, it was quiet, very quiet, green (very green), and was dripping with moss, epiphytes and ferns, and a few raindrops as well.

Out of nostalgia, we stayed at Momella Lodge, a tired old place that was first built for the filming of the John Wayne movie ‘Hatari’ back in the early 1960s. But what Momella lacks in updated decor and services, it makes up for in spectacular views of both Kilimanjaro and Meru, that is when the clouds don’t obscure the mountains. For two days we patiently waited, hoping for even a glimpse. When the clouds finally parted to reveal our first view of Kili, even the local workers cheerfully celebrated with a lightening of spirits. ‘Iconic’ is a word that is often overused, but in this case it is true to the mark. Kili, and later Meru, hung around for the rest of our time there, allowing numerous opportunities for photos from dawn through to dusk.

Day 2, 6:47pm (15 minutes after sunset); M.Zuiko 12-100mm PRO at 100mm (200mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ ⅓, ISO 800; raw file processed in Topaz Photo AI and Lightroom.

Creating this photo was a photographic balancing act. I wanted to use Hand-held High Res, but the giraffe would move in the brief time it took to create the file. I could have used a higher ISO, but the shutter speed would still be too low for HHHR. What to do. First and foremost—get the shot, then deal with the processing later. Upscaling 2x in Topaz solved the problem and gave me an 80mp tack sharp image.

Mount Meru, Tanzania’s second-highest peak, was a once a typical conical volcano. Similar to Mount St. Helens, it blew its eastern side away. Since then a new cone developed, though there hasn’t been any activity for over a hundred years. The ‘wall’ shown here, from the top to the base of the new cone, is one of the highest vertical drops in the world at 1.5km.

Day 4, 6:53am; M. Zuiko 12-100mm @ 86mm (172mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1/50, ISO 200; Hand-held High Res.

‘On Safari’

Despite being retired and on vacation, we decided to forgo the casual mornings and head out each morning at dawn for wildlife drives, taking a Thermos of milky Tanzanian tangawizi chai (ginger tea) with us. But one of the best opportunities we had for viewing wildlife was on our way into and through the park on our first afternoon. There is a distinct surge of excitement at the first encounter with giraffe, then zebra and Cape buffalo, and finally monkeys. Big beautiful, black and white Colobus monkeys with their white ‘beards’ and long white, fluffy tails, then Blue monkeys, deep in the shade and more difficult to successfully photograph.

Day 1, 1:33pm; 381mm (762mm efov) w/ MC-14 teleconverter; ƒ11 @ 1/160, ISO 1600; raw file processed in Lightroom and Topaz Photo AI

Less than 30 minutes after entering the park, we had our best views of Colobus Monkeys. At this point, I was hesitant to use ƒ8 as, with long telephotos, depth-of-field is limited to begin with. However with a steady hand, braced on the top of the truck, and a polite request to ‘Stop moving!’ (it really was polite, though perhaps a bit brusque!), the shot was made. This file also benefitted from some nurturing in Topaz to reduce the ever-so-slight movement of the monkey.

The typical safari-goer often doesn’t understand the needs of photographers in having clear sight-lines and enough light to stop even the smallest movements of animals and birds, and to prevent movement in the truck from ruining a great shot. Without other clients in the truck wanting to look-and-move-on, Laura and I had the luxury of patiently waiting and observing wildlife, giving us opportunities to ponder such things as how monkeys keep their fur so clean and soft and glossy-looking in such a dusty place, without using hair products!

The same excitement accompanies the sighting of each of the many brilliantly-coloured bird species: the green and yellow flashes of little bee-eaters, the bright yellow Northern Yellow White-eye, bronze and variable sunbirds and lilac-breasted rollers. Under the dazzling tropical sun, their iridescence is awesome in the true sense of the word. Capturing their fleeting forms in just the right light with just the right background is the supreme challenge! I am always envious of birders who are ecstatic with an audible confirmation or even a fleeting glimpse. Bird photographers need a whole lot more to realize true success.

Again, careful observation of behaviour combined with patience are the keys. We noticed how frequently other safari trucks stopped alongside us then, not immediately seeing any ‘big game’, started up and continued on, missing the birds and wildlife that begin to appear after only a few minutes of quiet, once the dust had settled. It is these observations and photographs that have so enriched our experiences of being ‘on safari’.

Day 3, 7:54am; 210mm (420mm efov); ƒ6 @ 1/50, ISO 3200 (Yes, it was dark in the understory); Lightroom + Topaz Photo AI

One of the highlights of Arusha National Park is the giraffe, giving the park the informal moniker of ‘Giraffic Park’. Seeing up to a dozen giraffes at a time was thrilling. Such gentle giants. We were sad to learn that during COVID, the giraffe population in ANP was almost wiped out due to the misguided belief that bone marrow from their neck was a ‘cure’ for COVID. This, in a country whose government under President Magafuli rejected any notion of the existence ofCOVID—go figure. Giraffe numbers have since rebounded and they are easily seen roaming around the park, through the lodge grounds, or popping up like periscopes amongst the low shrubs. With a face like theirs, what’s not to love!

From a photography perspective, the 100-400mm zoom was on the camera 90% of the time. I changed to the 12-100mm zoom (24-200mm efov) only for the landscape views of Kili and Mt. Meru. At times I used the MC-14, 1.4x teleconverter, and had some good success with it (see the Colobus Monkey and Baglafecht Weaver photos), but I also found that at times there was a very slight softening of details (see African Sacred Ibis photo). Even with noise reduction and subject sharpening, it’s not quite ‘there’. The other factor working against use of the teleconverter were the obvious heat waves that were magnified over long distances.

Image Processing

All images were processed in Lightroom on an iPad Pro, usually in the evening of the day they were made. Evenings were ideal because sunset was around 6:30pm followed by dinner and ‘down time’. Despite the shortcomings of Lightroom for iPad, I deliberately left the laptop at home to free-up weight. As well, the OM-1 connects directly and easily to the iPad via the same USB-C to USB-C cord used for charging. I like the intuitiveness of editing on iPad, using the pencil/stylus is ideal for creating adjustment masks. It allows for a lightweight, fast and effective workflow when travelling, even though Adobe continues to handcuff Lightroom for iPad despite having the power of the Apple ‘M’ chip (grumble-grumble-grumble).

Upon returning home, some of the images have also been processed through Topaz Photo AI. It’s the first time I’ve needed to venture away from Lightroom for processing but I found that while Lightroom is ideal for exposure, colour, and masking, Topaz provides superior raw de-noising and sharpening. I also welcomed the fact that the edits I performed in Lightroom while ‘on safari’ can be directly applied to the DNG file I re-import from Topaz into Lightroom—the best of both worlds.

@ 200%

@ 200%

At screen size, the photos are indistinguishable without very close scrutiny. At 100%, the Original raw is fine for small prints, but benefits from Lightroom Denoise + Sharpen. However, as this is a crop of 1712×2283 pixels, the file definitely benefits from the upsizing possible in Topaz to provide a more substantial 3424x4565px size for larger prints. Even at 200%, there is no discernible loss of sharpness. It’s not perfect, but to me, the trade-off is worth it. The only noticeable deterioration is in the slight loss of feather detail in the black primary wing feathers. I’ll post another blog specifically about the benefits and costs of Topaz.

As I continued with my shooting, I began to use ƒ11 less and ƒ8 more. ƒ8 provides more light (= faster shutter speed and/or lower ISO), and the loss of depth-of-field is negligible. I always began each shooting sequence at ISO1600 to ensure a sharp capture at high magnification. Once I get the shot, I begin dialling back to ISO 800, 400 and sometimes 200, when lighting and subject permit. I find I can hand-hold at 400mm (800mm efov!) down to about 1/30th, but that is only when conditions are ideal and the subject co-operates, which is rare when they are always moving whether to swish away the ever-present flies or to avoid predators. Additionally, even the slightest of breezes can set a branch swaying adding yet another challenge to bird photography. And then there’s the challenge of being in a truck with two other people moving around. I’m not complaining, just laying it out there. High magnification bird and wildlife photography in general has its challenges beyond finding your subjects!

Day 4, 1:12pm (on the way out of the park); 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ11 @ 1/1600, ISO 1600. I love this photo, having caught the bee-eater ‘doing its thing’, but I hate the distracting background. I believe in real-world photography which means I do not swap backgrounds, so this one I’ll need to work on a bit more.

Overall, I am truly thrilled with the success rate of my Olympus system. I am not exaggerating when I say I easily had 5 to 10 times the success rate than I when I shot full-frame Nikon. Why? It all comes down to a combination of lighter-weight gear, longer reach, and amazing stabilization. Did I get all the shots I had hoped for? Sadly, no. Some were my fault, mostly from not properly anticipating what the bird or mammal would do next, or I became too stabilization-dependent and didn’t take proper care to be steady. Others shots were missed due to focusing issues, particularly with birds-in-flight, a technique I really need more practice with.

That being said, the OMD/Olympus system is so efficient that I still have far more ‘keepers’ than I know what to do with.

I will follow up this blog with Part 2 with our first safari to Tarangire National Park—lions and elephants and vultures, oh my!

If you have any questions about safaris, gear, processing or the photos, be sure to add a comment.

Sign up to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Use the box below for subscribing. You email will never be shared.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field&Screen workshop at Workshops.

iPhone 11 Pro 2x camera—and, yes, the elephant was that close! But that’s Tarangire for you. (Photo made by Laura as, for once, I was driving!)