How well can Topaz PhotoAI and ON1 No Noise ’rescue’ images with motion blur?

Raw File Optimization – Part 2

This article is the second in a series exploring how to get the most from your raw files. The first was simply entitled Raw File Optimization and explored how to demosaic, denoise, and sharpen raw files using Lightroom Enhanced Noise Reduction, DxO Pure Raw, ON1 No Noise, OM Workspace, and Topaz PhotoAI.

I tested ON1 No NoiseAI plus TackSharp and Topaz PhotoAI Raw Noise with Sharpening on three recent photos that I would love to see improved.

We’ve all been there!

The sudden rush that accompanies that first view of a bird or mammal—we shoot first, then engage the thinking. Is my shutter speed fast enough for the telephoto lens I’m using? How can I increase the speed? Larger aperture? Higher ISO? Is there something I can brace myself against?

In an ideal world, we would have everything set and ready to go, but that’s not always the case. And if you’re on safari, or with others in a vehicle, you have that motion to deal with as well. Someone in the vehicle may shift in their seat to stretch a leg, or even yawn, resulting in movement of your platform, invariably, just when you press the shutter release.

There are also times when everything is set and still, but in dim light, motion blur remains a reality. Not only are birds and wildlife on constant alert for potential danger, they may also be under a dim tree canopy. Branches moving from the wind or from other occupants, even slight movement can translate into blurred images when shooting with telephoto lenses. It’s bound to happen!

Enter software such as ON1 NoNoise AI and Topaz PhotoAI. Let’s see what they are capable of.

Method

Photos

I chose three recent photos: one with only slight blur, one with definite blur, and a third that, well, let’s just see what the software can do.

1. Black-and-White Colobus Monkey (Colobus caudatus): This is a near full frame (4760x3570px) image made in the depths of the cloud forest on the slopes of Mount Meru in Arusha National Park, Tanzania. It is almost sharp, but slight movement of the monkey’s head seems to have caused the slightest of blur to the hairs surrounding its face, so it doesn’t appear to be camera movement. The photo was made with an Olympus OM-1 and M.Zuiko 100-400mm ƒ5.0-6.3 IS lens with the Olympus MC-14 1.4x teleconverter, at 381mm (762mm efov), ƒ11 @ 1/250, ISO 1600. The lens itself is tack sharp as we saw with the photos of the lion and catbird in the previous article. In retrospect, I should have trusted using ƒ8 and ISO 3200 which would have provided a shutter speed of 1/1000, two EV faster.

2. Olive Baboons Grooming (Papio anubis): Also made in Arusha National Park, this adult and juvenile would not sit still. Mom was grooming the kid, and when do kids sit still, especially when having their hair picked over! It was an overcast morning which, under a dark forest canopy, only added to the dimness of the scene. As well, there appears to be some camera movement, as I can see some hairs with double-blur. The 100-400 was at 210mm (420mm efov), but the dim lighting demanded ƒ6 @ 1/50, ISO 3200—not ideal. This image is a centre-crop of 2916x3888px within a horizontal frame.

3. Red-billed Oxpecker (Buphagus erythrorynchus) on Eland: This was a late evening shot, resulting in slower and less accurate focussing than expected. OM Workspace shows the focus point to be just ahead of the right foot of the Oxpecker as it clung to the back of an eland. Clearly, this is a case of operator error, so I take full responsibility for not getting the focus point on target! The photo was shot at 400mm (800mm efov) with the 100-400 zoom, ƒ8 @ 1/80, ISO 1600, and is an 1825×2460 crop. Yes, the oxpecker was far away, but I had yet to get a decent photo of one from our trip! It’s still not decent, but it’s better than nothing and makes for a good example to test just how far the software can go.

Processing

For each photo, I started with the original ORF raw file, edited in Lightroom. My goal, as always, is to re-create the photo as visualized in the field, using subtle adjustments of Exposure, White and Black Points, Highlights and Shadows, Contrast, White Balance and Tint. Adjustment Masks are applied as needed to shape the light; Lens Blur was applied to the Colobus Monkey photo.

Once the initial editing was complete, the ORF was exported from Lightroom, processed within ON1 and Topaz seperately, then each was output as a DNG file to be added back into Lightroom where the same original edits were then copied from the original and applied.

Treatments

Within ON1 NoNoise, I used both the NoNoise AI and Tack Sharp AI modules together, beginning with the Defaults, then adjusting the ’Enhance Detail’ as needed. Micro Sharpening was not applied beyond the default as it always appeared as too aggressive, making the results look ‘crunchy’.

In Topaz PhotoAI, Raw Denoise was used along with Sharpening using Motion Blur applied to the subject only. The mask was adjusted as needed to ensure only the subject was being sharpened. With the Oxpecker photo, I tried the Super Focus BETA with surprisingly good results. However, it took a couple of minutes to see the Preview results and another 10 minutes(!) to process the image. All processing was done on my M1 MacBook Pro with 16gb of ram. There must have been some seriously intensive number crunching going on as I was a bit surprised by how long it took. It felt like 20 years ago, when trying to send a photo over dial-up! But, I went on to do other things while it chugged along. Were the results worth it? We’ll see.

Results

In each case, I compared each treatment with the Lightroom base image, which had been run through Enhanced Noise Reduction and given appropriate sharpening, typically 80 with Masking set to 30. I’m pleased to say both ON1 and Topaz apps have the potential to achieve very good result when rescuing images from slight camera movement. Neither is good enough to rely on to perfectly correct mistakes, but when the mistakes are minor, they do a pretty good job. While I don’t think either quite matches up to the advertised improvements, both can make some recovery of IQ possible.

Colobus Monkey Of the three test images, this one came up with best results. In fact, the results are good enough for a full-size print 12×15” in size. It could even be up-sized to 16×20” with no loss of quality. However, of the three test images, this was also the largest in pixel size, the best exposed, and had the least amount of motion blur to begin with.

For proper viewing, click to open to view at full size (2700x1200px)

Overall, I prefer the Topaz results. To me, they appear cleaner, especially in the white cheek fur. The facial features also appear more natural. In the ON1 version, the facial features appear carved from wood or plasticine.

Baboons Grooming took a little more work. While the hair appears a bit coarse/crispy, the movement is mostly gone. Using the defaults produced an image with double fine hairs. By increasing both the ’Strength’ and the ’Minor Denoise’, this issue was partly solved, but not entirely. Back in Lightroom, I reduced Sharpening to ’0’ and I further reduced the crunchiness of the individual hairs by moving the Texture slider to -50, softening the coarse hairs into something more natural-looking.

For proper viewing, click to open to view at full size (1800x1200px)

I’m not completely happy with the ‘cheek fur’ as it looks a bit too soft and random. However, Topaz did the best job of sharpening up the area around the eyes of the closest baboon, which is the critical part of any wildlife photograph.

Oxpecker: Interesting results. I don’t think any of them adequately render the bird acceptably sharp for printing, but it could be used for ID purposes or a record shot posted online—not what I was hoping for, but then again, I didn’t give the apps much to work with.

For proper viewing, click to open to view at full size (1800x1200px)

Initially, I used Topaz’s Super Focus BETA, setting the Focus Boost to ’Minor’ and the Sharpening Strength to ’Medium’, but that was too high. Unfortunately, setting it to ’Low’ meant another 10-minute wait for results. However, the wait was worth it, perhaps. While the results were not nearly as ’crunchy’ looking, they still not quite up to a visual quality I was hoping for. It introduced an un-natural pattern to the fur and the Oxpecker, without its red eye ring, is a fail.

The ON1 file processed much faster and, at first glance, has a slightly more natural appearance. It managed to retain the red eye ring which Topaz completely lost. However, while the fur on the eland may look more natural, the Oxpecker itself looks forced. The Topaz version, at least, managed to keep, or generate using AI, some feather detail. So Topaz wins for the Oxpecker and ON1 wins for the fur of the eland, though, even the out of focus fur on the Lightroom version looks more realistic.

Conclusions and Discussion

First of all, it’s important to do everything in your power not to fall into the trap of needing to correct for motion blur. If a tripod or monopod isn’t practical,

- engage IBIS;

- brace your arms or lean against a support;

- relax your breathing;

- gently press the shutter release at the ‘bottom’ of your breath;

- open the lens aperture;

- increase the ISO.

- If you’re in a safari truck ora vehicle with others, ask everyone to be still.

Any or all of these help. While motion blur can be corrected, it is not ideal.

Secondly, do not expect much improvement from software correction. While this isn’t a definitive test, I have learned that very slight motion can be corrected to the point where full-sized prints at 300ppi are possible. But it also shows that the advertising is showing only best case scenarios.

It’s best to think of the improvements as a sliding scale of severity versus tolerance. The worse the motion blur is, the more tolerant you will need to be of how limiting the correction is. In more severe cases, such as the Oxpecker, the photo may only have limited use as a record shot. You can share an image like this online, but again, don’t expect to make large prints and be satisfied. It would work as a small image in a photo book, but it might be stretching it for a decent print any larger than 5×7.

OM-1 with M.Zuiko 100-400mm at 400mm, ƒ8 @ 1/80, ISO 1600; processed in Adobe Lightroom and ON1 No Noise

As far as which app to buy to correct blur . . . ? My go-to has become Topaz PhotoAI. It did an excellent job with the Colobus monkey and the Baboons. But a case could be made for ON1 No Noise, given its results for the Oxpecker photo. Depending on how often you need to correct and the types of correction needed, it may be helpful to have both in your arsenal.

And please, if you are sharing a motion-corrected image, we, the viewing public, don’t need to know it is motion-corrected. If you highlight the fact, then some viewers will become determined to ‘find’ artefacts, even if there are none there. If you don’t tell them and someone notices or suspects, then be honest with them. Explain the situation, but don’t get dragged into long-winded apologies or explanations. It is what it is. We do our best with the situations we are presented with and the tools we have. You could even play it up a bit, using it as an opportunity to engage the viewer, describing how dim the lighting was and how difficult the capture was. 😊

The bottom line is don’t expect miracles! If you are able to correct motion blur using software—great. But don’t count on it. Also, be conscious of the fact that you may think the correction is fine, when really, to an objective viewer who has no skin in the game, it may not be. As with any rescue mission, you need to be honest with yourself.

Thanks for reading! Please add your questions, comments, or discussion about correcting motion blur and the apps and techniques used in the COMMENTS below.

This work is copyright ©2025 Terry A. McDonald

and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the author.

Please SHARE this with other photographers or with your camera club, and SUBSCRIBE to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.

Total Lunar Eclipse—Landscape Composite Photographs around Guelph, Ontario

Or evolution by trial and error . . .

This is the third and final article about the Total ‘Blood Moon’ Lunar Eclipse of 13-14 March 2025. The first, Are you ready? provides background and a series of resources for photographing a lunar eclipse. The second is a First Look at Total Lunar Eclipse Photographs, with a couple of composites of the Moon at different phases.

The photographs presented below illustrate what I had originally envisioned when I was preparing for the Eclipse. Over the years, I have tried a few times to make photographs of a lunar eclipse, but, given the poorer equipment I had at the time and my limited experience, they didn’t turn out too well. I also found that a photo showing an orange-red moon sitting in the middle of the black background of the night sky was cool, but wasn’t terribly engaging. This time, I wanted more.

The biggest advantage of modern sensors, like the one in my Olympus OM-1, is how well they handle high ISO noise. Combined with advances in post-capture processing, including Lightroom’s Enhanced Noise Reduction (or DxO Pure Raw or Topaz Photo Ai or ON1 Photo Raw—I’ve tested them all), the quality of the base raw files and subsequent processed files has greatly improved. Finally, I could work with high quality base files, and it was thrilling!

Capturing the base landscape images

A full day before the eclipse, I went out to scout locations around my home city of Guelph, Ontario. Despite their fast pace and bright lights, I don’t really appreciate city landscapes, preferring to photograph scenes from rural and natural areas. To me, cities are ‘necessary evils’. I appreciate the advantages of city living in not having to drive far for amenities, but at the same time, I long for a quieter life out in the countryside away from the sirens and constant white noise. Oh well . , .

As I was planning the base landscape photos, I felt it was important to maintain a sense of authenticity for each view. Each landscape had to show the correct south to southwest aspect, one that would include all phases of the Eclipse. Each photo should appear exactly as if you were standing in the same location watching for the three hours it took for the Moon to pass through Earth’s umbra.

PhotoPills’ AR mode is essential for this kind of planning. At each location, after centring the PhotoPills Planning map on the app and navigating to the date and time of the Eclipse, I could view the eclipse superimposed on the sky. Perfect!

At sunset, on the evening of the Eclipse, I re-visited each location to photograph it. the view required an ultra-wide angle, so I set up the OM-1 with the 8-25mm set to 8mm (16mm with a 35mm sensor). I would have used my new Panasonic-Leica 9mm/1.7, but it wasn’t wide enough. Mounting the camera on the tripod, I set the aperture to ƒ5.6 and the OM-1’s High Res mode to ‘Tripod’, capturing each scene as an 80mp, 10368×7776 pixel image—plenty large enough for virtually any use. After correcting for wide angle distortion in Lightroom, I ended up with 9526×7145 pixels, or a 68mp image. Not bad for M43!

Each base landscape was processed in Lightroom. I had to switch to my laptop as Lightroom for iPad (still) does not have Enhanced Noise Reduction. The files probably didn’t need it, but I decided to err on the side of caution. Processing also included further reducing the exposure of the sky while keeping and even accentuating the brightness of the foreground. Sky masks and Linear Gradient masks worked their charm. Each landscape was then exported as a TIFF to use later in Affinity Photo.

Processing the Moon shots

Capturing the moon itself was relatively straightforward. I was able to work from the comfort of my driveway, as the view to the south and southwest was unobscured. Between each series of shots, I could go inside, warm up (it was –1 to –4°C) and have 10-minute cat-naps. When there was enough time between segments, i could begin working on images already captured. You can read about the details of the set-up and exposure in the previous article, as well as the initial processing

Once each Moon shot was edited, I went through them as a set to balance the exposure, highlights and shadows, and the colour temperature of the moon, reducing the shot-to-shot differences. This tweaking took longer than expected, but was necessary to ensure consistency from phase to phase. I ended up choosing 11 different phases: three are ‘pre-Blood Moon’ showing Earth’s umbra gradually passing over the face of the Moon, three images show Totality, and three more are ‘post-Blood Moon’ as the umbra recedes, with a full moon at each end.

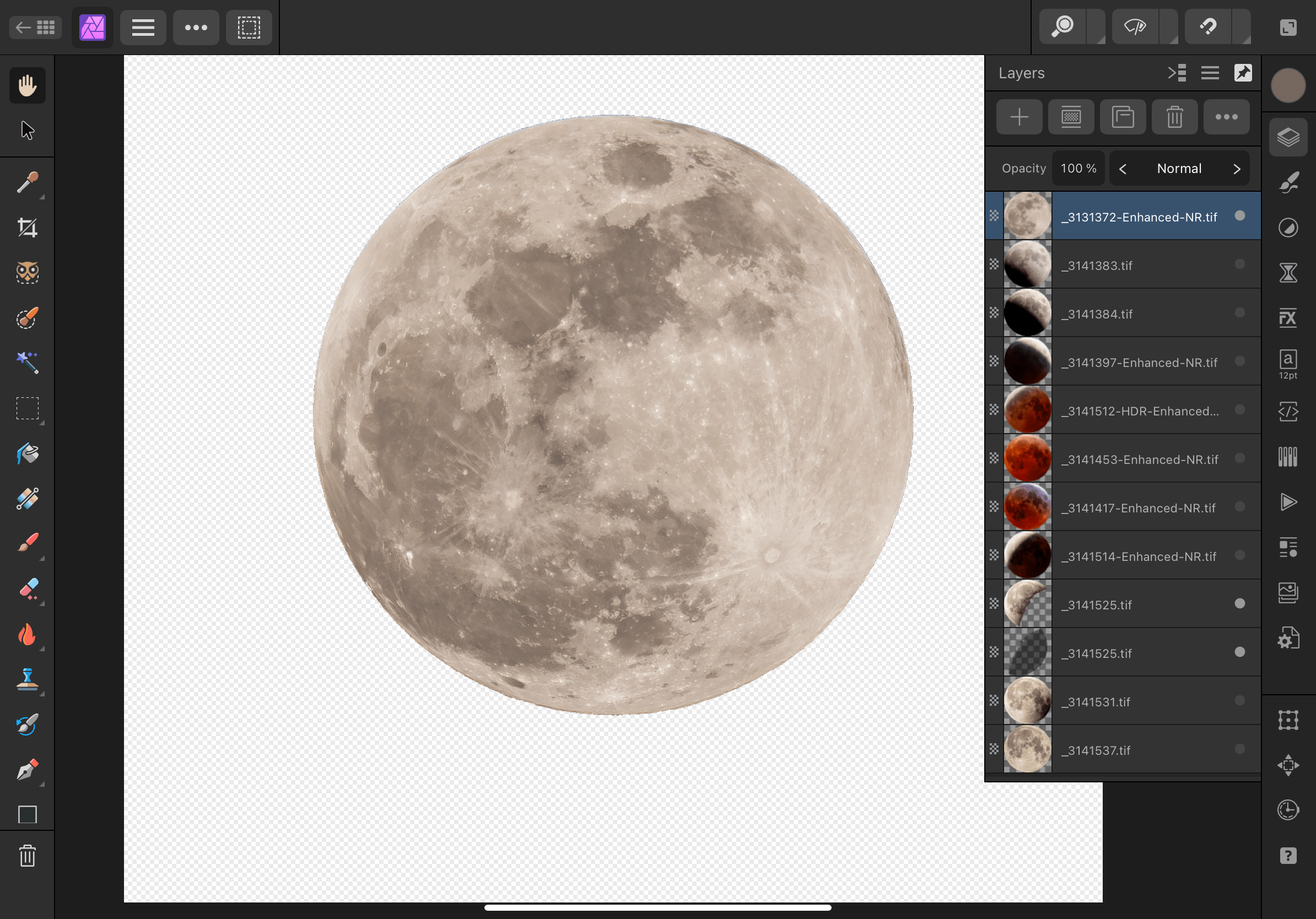

Working in Affinity Photo

At this point, I exported the 11 Moon images from Lightroom as 16-bit TIFF files. I could have used JPEGs but, with compression and sharpening, they reduce overall image quality. The TIFFs were then brought into Affinity Photo as a ‘New Stack’. In Lightroom, I had carefully cropped each photo to centre the Moon and to maintain phase-to-phase consistency, but I wanted the circles of the Moon aligned, so I toggled on ‘Align Source Images’. The app did precisely as directed, and I carried on. The Stack was ungrouped allowing me to work on each layer individually. I could have set them up as 11 different files, but opening and closing each file would have become tedious. Working on them as 11 layers was much easier. My goal was to remove the black background of the sky, leaving just the Moon on a transparent background.

Everything looked great, but something was amiss. It was sometime later that I realized each of the eleven Moon images had been rotated. Affinity Photo had done its job correctly by aligning the various craters and features of the Moon. But something wasn’t right. I literally sat there scratching my head for a moment. It was then the light bulb of understanding flickered on—I realized that, over a period of three hours, our view of the face of the Moon changes in 3-dimensional space. Oops!

Rather than trying to undo all the alignment, I scrapped that set of images and re-imported them as a New Stack, but with ‘Align’ toggled off. Lesson learned. Part of me wonders if anyone would have noticed, though I’m sure the true Skywatchers would have alerted me to my error.

From there, it was one trial-and-error after another. I do this to myself—I set a goal, then learn the the ins-and-outs of an app while trying to achieve that goal. Working through a series of prescribed lessons without a clear and applicable end goal doesn’t keep me engaged. So I try something, then do an online search for a solution, then try it again.

I enjoy working with Affinity Photo, but haven’t used it frequently enough to learn all of its inner workings. I had originally learned many of the techniques in Photoshop and, thankfully, Affinity Photo isn’t all that different. In fact, the iPad version is far more complete than the iPad version of Photoshop. Affinity Photo on iPad is like Photoshop on desktop. It’s brilliant (and much less expensive). Kind of makes me wonder why Adobe knowingly continues to cripple its iPad version of Photoshop. I’m glad I ditched it.

By the way, there is nothing quite as intuitive as editing photos on iPad. With a $25 stylus (pencil), it is it even more so. Tapping and drawing with a fine tip is far more accurate than my pudgy finger or using a mouse/trackpad (apologies to Steve Jobs, who as always pro-finger and anti-stylus—😉)

Now, for the composite—more trial-and-error

Once each of the 11 Moon images was prepped in Affinity Photo, I exported them as 16bit TIFFs. I could have used PNGs to maintain transparency (JPEGs do not), but I also needed to maintain overall image quality.

Opening one of the base landscapes, I then copied and pasted the 11 layers of Moon images. In an attempt to maintain realism, I positioned the moons in an arc across the night sky. As a guide, I drew an ellipse to help with smooth positioning and made constant use of Align > Space Horizontally as well as plenty of nudges.

It looked great, but wasn’t quite ‘there’. With coaching from my better half, Laura, we decided each Moon was much too large in the sky. As well, the sky needed to be even darker, while still maintaining that astronomical ‘midnight blue’.

With trial and error, I ended up reducing the size of the Moons to about ½, and repositioned them on the ellipse/arc. After another assessment, we decided it still didn’t look right, so I tried arranging them in a straight line. Nope—it looked too, well, linear to be realistic.

Finally we settled on a gentler arc and that seemed to do it.

From there, I was able to copy and paste the 11 Moon layers onto each background scene. With further tweaking of each individual photo, I ended up with three landscape composites I was pleased with and one ‘meh’. Sadly, the ‘meh’ view is of one of our favourite places in the Arboretum at the University of Guelph. During the day, there is plenty of detail to draw you in but, at night, it appears too flat-looking compared to the others. Oh well. Live and learn.

Have a look at each of the four then, down in the Comments, let me know which one(s) you prefer and why.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions about the equipment, apps or techniques discussed above, be sure to add a COMMENT.

Please take a moment and SHARE this with other photographers or with your camera club.

To receive an email notice of new articles, SUBSCRIBE below.

Text and photos are copyright ©2025 Terry A. McDonald

and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the author.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.

First Look at Total Lunar Eclipse Photographs

. . . and a review of the experience.

Last night was a long one, but well worth it. Over the course of six hours, from before midnight to just before 6am, I took photos every 20 minutes or so, depending on the ‘action’ in the sky above. Some were made 5 to 10 minutes apart. Exciting, yes, but also a real learning experience.

I used my M.Zuiko 100-400mm ƒ5-6.3 IS lens, which is equivalent to a 200-800mm in 35mm sensor terms. It pulled the moon in, but it still did not occupy even ¼ of the sensor. I tried a few shots with the MC-14 1.4x Teleconverter, but I wasn’t entirely happy with the sharpness. With the OM-1 attached, the lens was firmly mounted on a sturdy Manfrotto tripod. As expected, according to the research I did ahead of time, exposure varied widely. Thanks also to a graphic shared on FB by Peter Baumgarten which also showed the variance in exposure over the event.

All metering was done using the OM-1s Spot Meter mode—essential for this kind of work. I altered exposure with each shot—+1EV, neutral, and –1EV, sometime –2EV—but the images that seemed best were at normal exposure for the dim Moon and +1EV for the bright Moon.

Trying to keep the Moon in focus was a problem I shouldn’t have had, but I messed up. When the Moon was bright, I used single-point AF to lock in the focus, then switched to Manual so the AF wouldn’t need to keep focusing. However, twice I inadvertently changed the focus when zooming between 400mm and 100mm and back again—Duh!—and had to re-acquire focus on a decidedly dim Moon near Totality. As a result, some photos are not as sharp as I would like them to be.

Then there is the motion blur to content with. At ISO 3200, the slowest shutter speed occurred at Totality, a measly ⅖ of a second. Not great for a moving target! I could have opened up ⅔ EV to ƒ6.3 and brought the speed up slightly but, as is always the case with photography, I decided to trade a slightly sharper slightly blurred image for a less-sharp, slightly blurred image. Oh well!

The files were processed in Lightroom (not Classic), with the ISO 800 and 3200 shots run through Enhanced Noise reduction, then sharpened. It took a fair bit of work with exposure, contrast, highlights, shadows, white and blacks to nail just the right balance of black sky, shaded details and the over-exposed highlights that occur just before and after Totality—the Japanese Lantern effect, I am told.

The files by themselves look good but, as individual photographs, they don’t really tell the story. I knew I would be making composites; it’s just a matter of deciding whihc photos and how many to add. The composites above were made in Affinity Photo by placing individual files on a background of the night sky—one of the frames I shot at 100mm.

I have plans for a few different composites that are still in the works. Earlier Thursday evening, just at sunset, I went around to five locations in Guelph, shooting ultra-wide landscapes at 8mm, with 80% sky. My goal is create composites with these photographs to put the Eclipse into context that people might recognize. More and more people I’ve spoken with either forgot the Eclipse or didn’t manage to get out of bed for it, so this will help them see what all the excitement was about. The five base landscapes were all shot specifically including the South and Southwest sky, exactly where the Eclipse occurred. PhotoPills AR really helped to ensure correct alignment.

The landscape composites will be fun to do, but will take more work extracting the Moon from each file, without the surrounding black sky—something for this weekend.

If you had a Eclipse experience, be sure to tell us about it in the Comments section below.

Thanks for reading! Please add your questions, comments, or discussion about the Lunar Eclipse, and/or the equipment and techniques used in the Comments below.

This work is copyright ©2025 Terry A. McDonald

and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the author.

Please SHARE this with other photographers or with your camera club,

and SUBSCRIBE to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.

Are you ready? Rare ‘Blood Moon’ Total Lunar Eclipse Thursday night to Friday morning!

Get your sleep now because you might just be up all night later this week. Across all of Canada and down through the Unites States, Central America and South America, if skies are clear, we will be retreated to a Total Lunar Eclipse—a rare ‘Blood Moon’ Total Eclipse.

I do a lot of photography, but rarely have I ventured into night photography. I loved photographing the Total Solar Eclipse in April of 2024, but find that all too often, the night skies here in southern Ontario are either too bright or too cloudy for success.

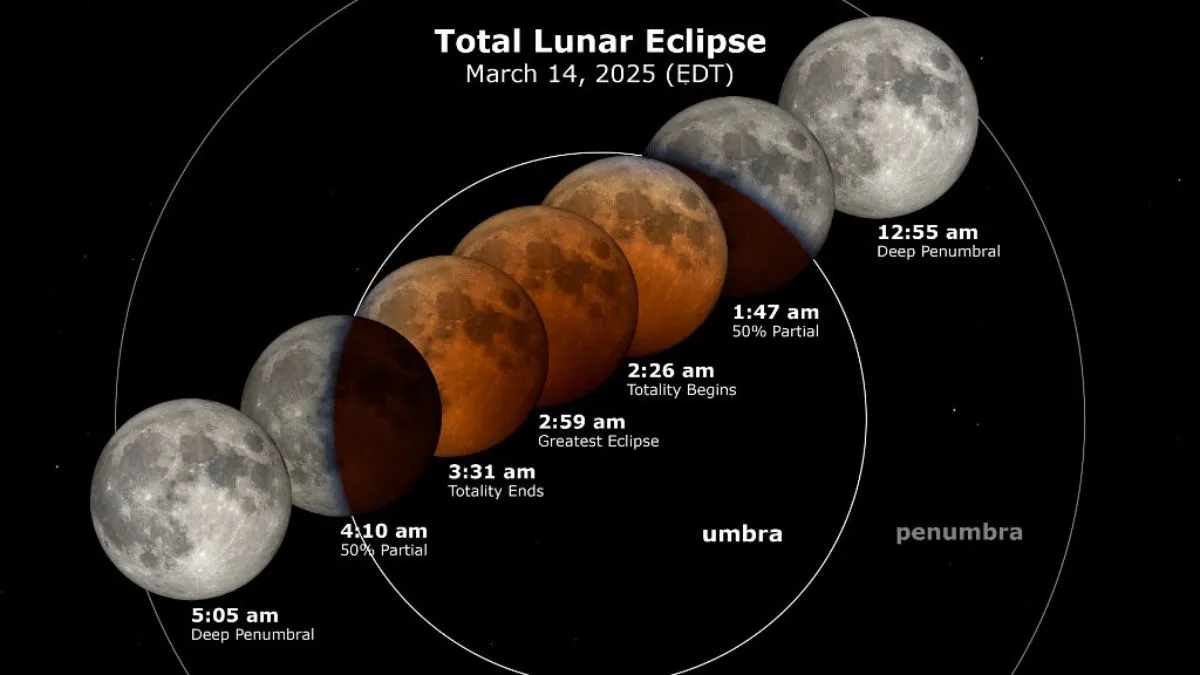

Lunar Eclipse: March 13-14, 2025

A Lunar Eclipse is different. It happens when Earth’s shadow travels across the face fo the moon, turning our Moon a deep orange-red colour. It is also a much slower process, taking about 6 hours from start to finish. That’s why I recommend getting your extra hours of sleep in now.

Here’s some background about the eclipse from Space.com. this article has some very specific timings and descriptions of what’s happening when.

We’ll start with the timings. I pulled these times from TimeAndDate.com and did my best to confirm the times across Canada.

| Pacific | Mtn | Sask | Central | Eastern | Atlantic | Nfld | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start of Penumbra | 8:57pm | 9:57pm | 9:57pm | 10:57pm | 11:57pm | 12:57am | 1:27am |

| Start of Umbra | 10:09pm | 11:09pm | 11:09pm | 12:09pm | 1:09am | 2:09am | 2:39am |

| Start of Totality | 11:26pm | 12:26am | 12:26am | 1:26am | 2:26am | 3:36am | 4:06am |

| End of Totality | 12:31am | 1:31am | 1:31am | 2:31am | 3:31am | 4:31am | 5:01am |

| End of Umbra | 1:48am | 2:48am | 2:48am | 3:48am | 4:48am | 5:48am | 6:12am |

| End of Penumbra | 3:00am | 4:00am | 4:00am | 5:00am | 6:00am | 7:00am | 7:30am |

Next: equipment, composition, exposure and post-processing. You may want a shot showing the moon phases above a particular scene or landscape/cityscape, but you might also want a telephoto shot of the deep red of the moon at totality. If you have two cameras and two tripods, you could do both.

How to . . .

So, you want to photograph the Eclipse . . .

As I said, I am no expert in this field, so I have put together some resources to help you (Note: links below open in new tabs). But first, an overview from Gordon Laing:

- Practical Astrophotography: How to Photograph the March 13th Lunar Eclipse

- Photography Life: How to Photograph a Lunar Eclipse

- AstroBackyard (the most complete): How to Photograph a Lunar Eclipse

- PhotoPills video (8:53): How to Plan a Photo of the Total Lunar Eclipse of March 14th, 2025 | Step by Step Tutorial

A few key things to remember are to:

- Make sure you charge your phone or tablet and your camera batteries!. You will likely be out for a few hours.

- Stay safe. This is happening over night. Go with a friend or at least let someone know where you are and when you expect to be back.

- Use a tripod. Your arms will thank you.

- Switch your camera to spot metering mode. The spot should be over the Moon.

- Bring and wear a small headlamp that can be set to Red/Night Vision. This will allow you to see without disrupting your night vision.

- Keep your shutter speed as close to 1/125 as possible by adjusting the ISO. At slower shutter speeds, the moon will appear blurred—remember you and and the moon are moving relative to each other. Even if it seems to be very, very slowly, there is enough movement to demand as close to 1/125 as your ISO will allow.

- Be prepared to change your ISO as the Eclipse evolves. The Moon will grow more and more dim, yet it is still moving, so you want to keep the shutter speed up. Remember, noise can be cleaned up in post-processing (see Raw File Optimization).

- Head out Wednesday evening to plan where you will be to get the shots you want. Seeing things ahead of time and standing there planning for where the moon will be during the eclipse will provide greater confidence for success on the night of.

Check the weather

I’m not sure where I’ll for this. Much depends on how clear the sky forecast is. Here are some sites to check:

- Windy (online and iOS / Android) has excellent, predictive maps for weather, clouds, etc.

- ClearDarkSky.com: Clear Sky Chart

- ClearDarkSky.com: Light Pollution Map

- TheWeatherNetwork.com: Cloud Map

There are apps for that

An app you may find helpful is PhotoPills. It’s free to download and checkout before forking over any cash. I have not made much use of it other than for planning for the Total Solar Eclipse last year. However, I see they have a very good YouTube video to help you get started. Also, I noticed on the PhotoPills website a number of free downloadable “Guides to Photographing . . .”, once you’ve provided your email. They have a free 143-page Moon Photography: The Definitive Guide (2024) and, most specifically, a 108-page Lunar Eclipses 2025: The Definitive Photography Guide. To get your guide, go to the PhotoPills.com > Academy > Articles and you will see a long list of very helpful guides for a number of outdoor shooting situations.

The other app i use is The Photographer’s Ephemeris (TPE). It is both a native (Desktop / iOS) app and a Web app. I find TPE much easier to use than PhotoPills and it seems photographer John Pelletier agrees in his comparison in 2020.

So, are you ready? The countdown is on—just four days to go! Good luck and all the best of luck for clear skies!

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions, comments, or discussion about the upcoming Lunar Eclipse, be sure to add a comment.

This work is copyright ©2025 Terry A. McDonald

and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the author.

Please SHARE this with other photographers or with your camera club, and consider subscribing to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.

New Lens! 9mm/1.7

Astrophotography, here I come!

For years, I was a prime lens kind of guy. But with the high optical and build quality of the OM System M.Zuiko lenses, their zooms especially, I was thrilled to be able to collapse my lenses down to three zooms which cover every focal length from 8mm to 400mm (16mm to 800mm in full-frame equivalents): the 8-25mm/4 PRO, the 12-100mm/4 PRO and the 100-400mm/5-6.3 IS. I added the 60mm Macro as a specialty lens, much as I’ve just done by purchasing the 9mm/1.7 prime lens.

ƒ4 has never slowed me down. Certainly the OM system zooms are sharp wide-open, something I did not experience with my Nikkor zooms. Shooting in low light situations of dim cathedrals and at the edge of light out in the field, I’ve always found that the OM’s IBIS covers slow shutter speeds and, when needed, I could bump the ISO. Any noise issues are effectively eliminated with Lightroom’s Enhanced Noise Reduction (see my review of the various Raw File Optimization treatments from earlier this year). So why a faster lens?

From what I’ve read and through my earlier attempts at Astrophotography, I’ve learned ƒ4 just doesn’t cut it.

Nikon D800E w/ 18-35mm at 18mm; ƒ4 @ 15 seconds; ISO 3200.

Astrophotography Backgrounder

Last month I attended an excellent webinar sponsored by OM Systems (the YouTube is available HERE). While much of it dealt with winter photography, photographer Peter Baumgarten also discussed astrophotography. As it turns out, the Milky Way begins to be visible in the southern Ontario night sky in late February and stays around right through the summer.

I have a lot of respect for Peter. He is a dynamic and very creative photographer, recognized as an Olympus Visionary/Ambassador. OM System includes his instructions for astrophotography in an online article, Astrophotography 101. I plan on having it up on my phone as I venture into this new realm of seeing. For added inspiration, I recommend visiting Peter’s website at CreativeIslandPhoto.com. You should also check out Landsby’s Guide To Stargazing & Aurora Viewing In Ontario and the Ontario Parks Blog. Ontario has a few ‘Dark Sky’ areas that will provide the best viewing conditions. The RASC has a map showing dark sky preserves across Canada and there’s also DarkSiteFinder.com (who just reminded me of the Lunar Eclipse this month).

Olympus OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 8-25mm PRO at 8mm (16mm efov); ƒ4 @ 20 seconds, ISO 400

How did I decide on the 9mm Summilux?

It was helpful that DPReview did some of the leg-work for me. In a 2023 article, they compared four top ultra-wide primes for M43 that fit the niche for astrophotography:

- Laowa 7.5mm F2;

- Meike 8mm F2.8;

- Panasonic Leica DG Summilux 9mm F1.7 ASPH; and the

- Samyang 10mm F2.8 ED AS NCS CS.

Although the P-L 9mm is the most expensive of the four, (tied with the Laowa), it is also head-and-shoulders above the rest in image quality AND it has autofocus. ‘So?’ you ask. ‘What’s the big deal about AF for stars? Do you need AF for astrophotography? Does it even work?’ Surprise! OM camera bodies have this wonderful feature called StarrySky AF!! Have you ever tried focussing on stars? With StarrySkyAF, there is no more guess-work or peering through magnified viewfinders to nail down focus. It’s a great feature!

Additional reading from Amateur Photographer and Photography Life as well as some M43 forum discussions helped to validate my decision, so I ordered the lens.

First Impressions of the P-L 9mm/1.7

I was thrilled that Camera Canada had the lens in stock and was able to ship it at no extra charge, with next day delivery. Talk about service! I have had nothing but excellent service from Camera Canada and can highly recommend them. They are based in London, Ontario, with their two ‘bricks-and-mortar’ locations operating as Forest City Image Centre. It’s the best of all worlds: Canadian-owned small business with online convenience, great pricing, and excellent service.

However, upon opening the box and holding the lens, I must admit to feeling a little underwhelmed, even disappointed, by the feel of the lens itself. Next to my OM System M.Zuiko lenses, the Panasonic-Leica seemed, umm, in a word, cheap—not inexpensive cheap but with a cheap feel to it. In all fairness, nothing rattled, and the focus ring is smooth; it also attached to the camera snugly—all good things. The lens is also a diminutive, which I appreciate, and the poly-carbonate lens body is certainly feather-light. But the lens does not exude the solid build quality, the ‘heft’ and feel of my OM System lenses. Even the plastic used in the lens hood doesn’t feel as robust as the lens hoods of my M.Zuikos. To look at it, and pick it up and feel it, the 9mm is clearly Leica in name only. But, perhaps I’m not being fair; it may well be Leica-quality in optics, which is the most important thing, but that remains to be tested.

So why didn’t I purchase the OM System M.Zuiko equivalent? Simple. There isn’t one. And worse, it’s not on their Lens Road Map. Why? Why? Why? OM Systems makes superlative, industry-leading, sharp, fast primes—why not at 9mm or 10mm?? Both 18mm and 20mm are such common focal lengths amongst the serious FF crowd. I loved my Nikkor 20mm/2. But, M.Zuiko primes skip right over from the 8mm/1.8 PRO Fisheye to the 12mm/2. Both are excellent lenses, but I didn’t want a fish-eye and 12mm is too narrow for the kind of coverage I wanted for astrophotography. OM System does offer the excellent M.Zuiko 7-14mm/2.8 PRO zoom, but it is big, it’s bulky, and it overlaps my existing and more useful zoom range of 8-25mm. And, at $1550, the 7-14mm it is also beyond my means.

So, the 9mm it is and the proof, they say, is in the pudding. Bring on the clear nights! 3am alarm here I come!

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions, comments, or discussion about M.Zuiko lenses, the OM-1 or the Panasonic-Leica 9mm/1.7, be sure to add a comment.

This work is copyright ©2025 Terry A. McDonald

and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of the author.

Please SHARE this with other photographers or with your camera club, and consider subscribing to receive an email notice of new blogs.

Have a look at my work by visiting www.luxBorealis.com and consider booking a presentation or workshop for your Nature or Photo Club or a personal Field & Screen workshop at Workshops.