Africville

Tucked beneath the MacKay Bridge to Dartmouth on the Halifax side is a lovely, green city park down by the waters of Bedford Basin. Despite its great location right on the water, it is completely cut off from the rest of the city by industry and railway tracks—accessible only by car or bike, and not by public transit. There is a museum, lots of green space, a ball diamond and children’s play area, but it has no sidewalks, no water, no sewage connections. It is all that remains of a once thriving community.

Where the sidewalk ends, Africville begins.

Imagine being granted land by the Crown for remaining loyal during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812—just like thousands of other Loyalists: combatants, non-combatants and their families. But, unlike all the other Loyalists, you were never given a deed to your land. And, unlike everyone else in Halifax, you are never provided with water and sewage infrastructure; no electricity, no garbage collection, no street lights, no police, fire or ambulance services—basically nothing. How could this be?

Then, on top of having no services, busy railway tracks were put through the middle of your community right next to the houses. Then, the city decides to put the municipal dump right next to your church. Then a prison. And a slaughterhouse. And an infectious disease hospital. And, the city’s sewage outlet is put into the Bedford Basin right at your community and where you fish for a living, and swim for recreation. Being Baptist, you are baptized by full immersion—in the same water.

Despite all of this a thriving, loving, vibrant community developed. This was Africville. For over a hundred years, the community not only existed but flourished. The residents may not have had much, but they provided for themselves by themselves, opening small businesses and running small farms. A real community of people developed, people who looked after and looked out for one another.

Then, along comes the city in the 1960s and deems the land ripe for ‘urban renewal’—not for the folks living there, but for industry. The 80 families totalling 400 people were forcibly evicted from their homes, their gardens, their small-holding farms, their businesses, and the centre of their community, their church, all of which was then bulldozed. Then, the city never ended up using the land for the purposes it was confiscated for.

Their land was not ‘expropriated’ as only a few ever received any compensation for their losses. Most were carted off to government housing, their belongings thrown into garbage trucks to be taken with them.

This is Africville. Loyalists, just like every other Loyalist community across Canada, with every right to live out their lives and the lives of their descendants—except for one key difference. Need I tell you that these Loyalists were Black?

After the Revolutionary War, formerly enslaved people from across the new USA who were loyal to the Crown, swarmed to the dockyards of New York to be added to the Book of Negroes, then transported to the British colonies, now known as Canada, with the promise of land and government assistance to get started farming. Needless to say, for this group of Black Loyalists, and a great many others, the promises were hollow. They were left wayward until the land at what came to be known as Africville was provided to them—but not until 1849, decades after the War of 1812 and almost 75 years after the Revolutionary War.

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

— Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As a descendent of immigrants, this story is significant to me but I found it impossible to capture this injustice as a photograph or photographs, especially with such a bright blue-sky day. While Canadians like to celebrate the role of Upper and Lower Canada as termini to the Underground Railroad, it is just as important to recognize the series of injustices that were occurring at the same time and afterwards.

Pier 21

It was a very different story for our ancestors. The day before visiting Africville, we visited the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21 on the Halifax waterfront, where over 1 million immigrants arrived to Canada between 1928 and 1971. They were white immigrants as that was Canada’s official policy up until the late 1960s.

Though my Grandfather, at age 3, and Laura’s Grandmother, at age 6, arrived to Québec 20 years prior to Pier 21 opening, visiting the Pier and seeing the exhibits was an emotional reminder of how many Canadians arrived and began their new lives here.

Not so for the Black Loyalists of Africville and their descendants.

For many of us—Scottish, English, Irish, Dutch, German, Czech, Polish, Italian, Greek, and other white Europeans—it is a shared history, a shared heritage. As Canadians of European heritage, we might come to believe Canada is somehow immune from the racism exhibited south of the border.

Not so. Just ask a person of colour.

Friends of ours have too many stories to tell of both subtle and blatant racism by individuals, and the systemic racism that still pervades Canadian society. You may be thinking ‘What racism?” Exactly. As whites, we have the privilege of being blissfully ignorant of it, unless we know people of colour.

Our history classes in school only ever spoke in broad positive ways of the opening of Canada, the great railroad connecting the continent coast to coast, the ‘opening of the west’, the farming prosperity of the Prairies, and the endless forests for timber. It was never phrased as a ‘conquest’. No, that was for the Spanish down in Mexico or the Americans who shot bison from railway cars by the thousands.

Yet, it was, clearly, a conquest—of the original inhabitants of this land. The Canadian government set out a programme of forced assimilation through starvation, using children in experimentation, and the loathful system of residential schools, which have left thousands of indigenous people in Canada with generational trauma. Those decisions, those attempts at forced and legislated elimination of indigenous cultures are now considered a form of genocide.

If you’re feeling uncomfortable with this, well, that’s a good thing.

Being offended is part of learning how to think.

—Robert Fulford

As immigrants, we might well feel offended to think that the Canada we knew and were taught about, one which we have built our history around, is not really the Canada that was. Even at the time, people spoke out in protest and in opposition to the decisions taken by the government, but their protests fell on deaf ears.

Peace by Chocolate: One peace won’t hurt.

So, stopping in Antigonish today, on our way to Ingonish in the Cape Breton Highlands, was important for the three of us (we picked up our daughter, Allison, two days ago from her flight to Halifax).

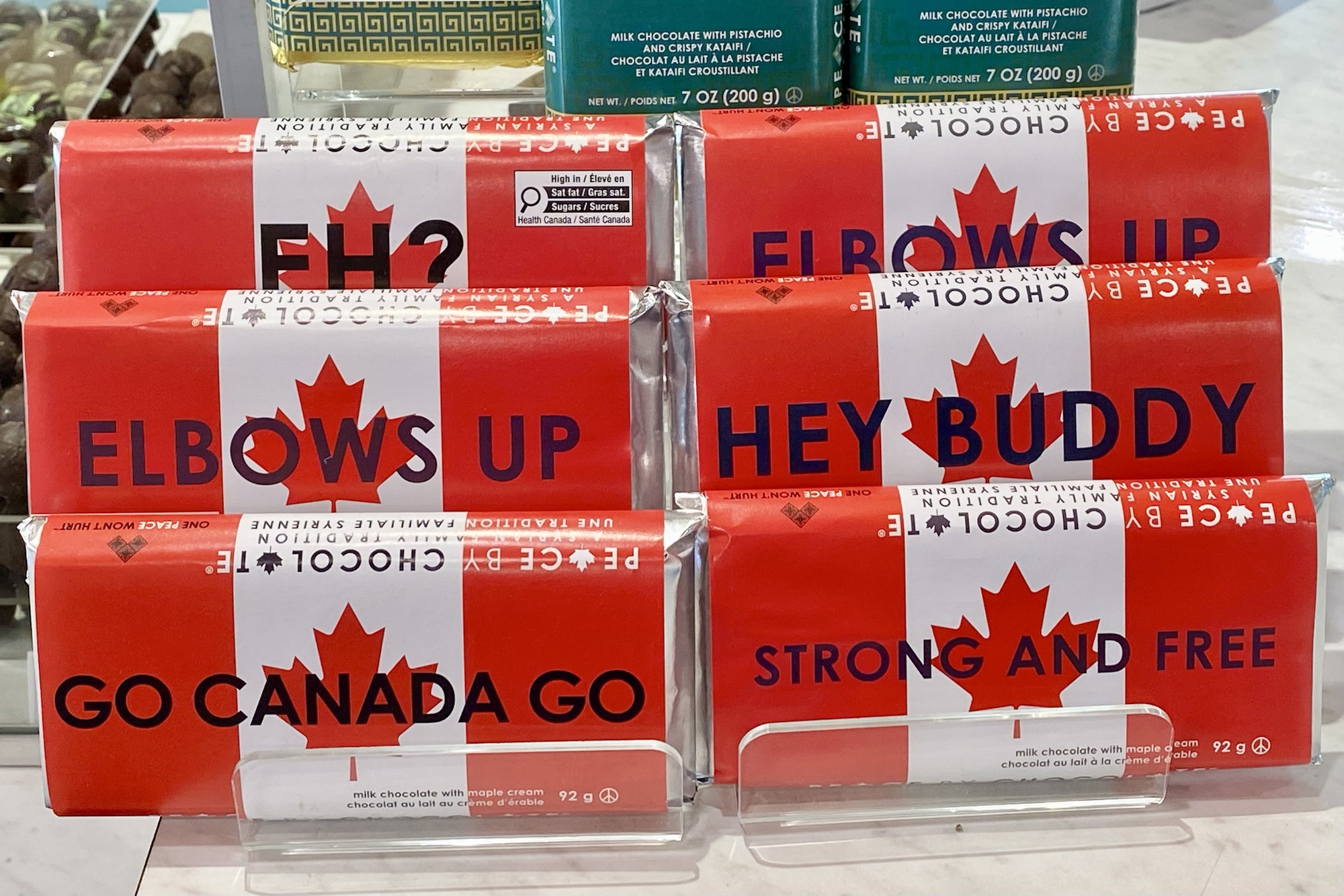

Antigonish is the home of the Hadhad family. They immigrated to Canada in 2015, fleeing the civil war in Syria. Their chocolate factory in Damascus had been destroyed, so they were starting over again, with very little. Perhaps you’ve seen the movie or read about their Peace by Chocolate success story.

For us, it was the realization of finally visiting the ‘home’ of their success story, their shop in downtown Antigonish. The best I could do was to take a few snapshots to convey their core value of promoting peace, multiculturalism and inclusiveness through the sale of their chocolate and philanthropy through their non-for-profit organization Peace on Earth Society.

Other than Indigenous peoples in Canada, we are all immigrants. As immigrants, being aware of our collective failures as well as the successes of Canada’s immigration story is an important part of being Canadian. To paraphrase Spanish philosopher George Santayana, if we don’t understand our history, we are doomed to repeat it.

Thanks for reading! Be sure to add to the discussion with a question, comment or observation in the COMMENTS section. Here’s a photo of Cape Breton to whet your appetite for the next post.

OM-1 | 20mm | ƒ5.6 @ 1/200, ISO 200, POL, HHHR | Lightroom

Discover more from luxBorealis Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Trackbacks