Just 12

American photographer Ansel Adams once said,

“Twelve significant photographs in any one year is a good crop.”

How was your crop from this past year?

If you’re not familiar with Ansel Adams, he worked through the middle 60 years of the 20th century making spectacular black-and-white photographs of national parks and natural areas in California, mostly with large format cameras. His best-known works were very large black and white prints, handmade from negatives of 4”x5”, to 8”x10”. In his early days, he would trek through Yosemite National Park, summer and winter, carrying a dozen or so glass plates at a time. Even with the switch to sheet film, he still had to carry each pair of sheets in large film holder that was inserted into the camera back, one shot at a time.

Sold via Christie’s (14¾ x 19”) in 2016 for USD47,500. A larger 38×60”, hand-made black-and-white print once hung above the Adams’s fireplace.

This is all to say Adams never had the convenience of auto exposure, burst photography, bracketing, or HDR exposures. Nor did he have zooms. His three ’walkabout’ lenses, included a 90mm wide angle of (around 27mm equivalent), a 150mm ‘normal lens’ (50mm efov) and a 210mm short telephoto in the 65mm range or perhaps a 300mm (108mm efov). It was not only the camera, lenses and backs that were encumbering, his work also required a heavy wooden tripod and black-out cloth.

It is said that good art is the product of limitations—Ansel Adams is certainly a testament to that. For more on how constraints stimulate thinking, read this from verybigbrain.com. Even the great film-maker Orson Welles is known to have said:

“The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.”

Therefore, given the limitations Ansel Adams faced, making 12 significant photos in one year was an achievement, though he regularly made even more. For a moment, consider putting yourself in a similar situation, going out for a weekend of serious photography to an amazingly beautiful natural or wilderness area with only three lenses, a tripod and, say 24 exposures. The effort you put into each exposure would be significant and you sure wouldn’t waste any on bracketing!

This photo is the successful product of learning a new technique: hand held focus stacking with my telephoto zoom lens.

Olympus OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 100-400mm at 227mm (554mm efov); ƒ6 @ 1/1600, ISO 800; stacked JPEG processed in Lightroom

So what’s my point here?

I encourage you to look back over the photographs you made in the past year and try to distill the best of your best down to 12 different images. Only 12. Not 13 or 15 or 20. Just 12.

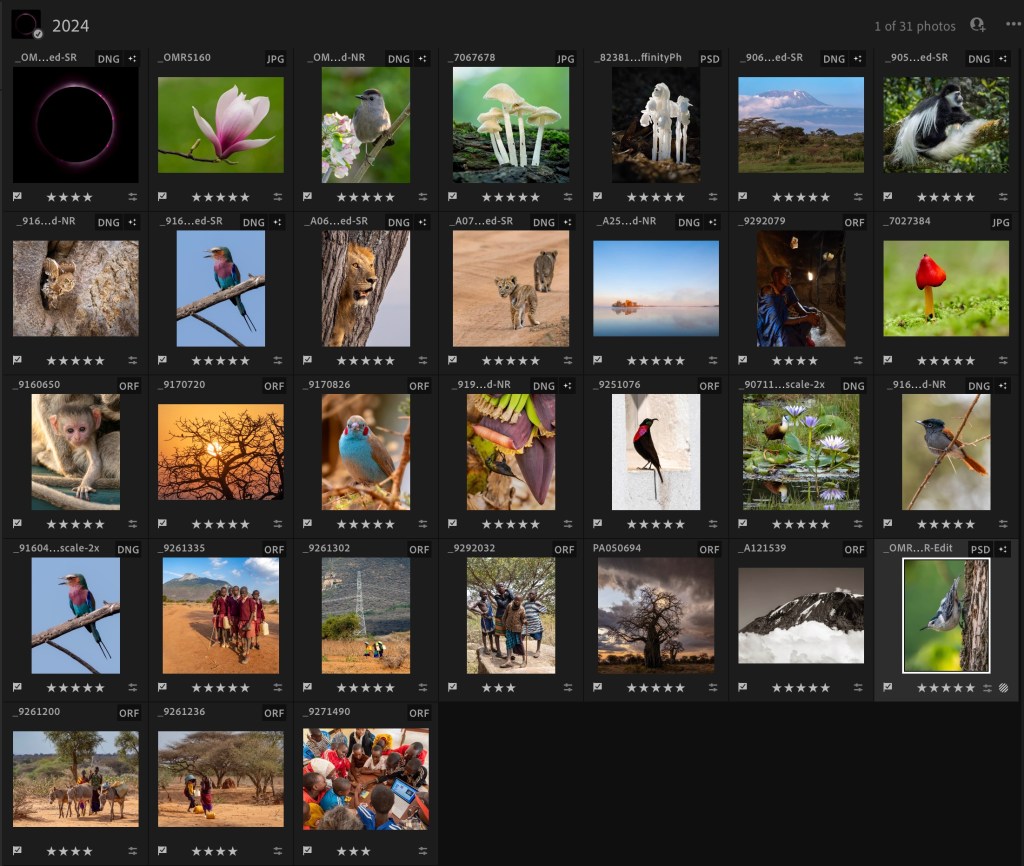

When I take on this task, as I do each year, I break down the year into a series of ‘sessions’, ‘scenes’ or ‘subjects’. I may get two or three top-tier images from one particularly engaging moment or session, so in this exercise, I include only one image from any one scene or session. I just went through my 2024s and came up with 31 (see photo). Now the real work begins!

Looking back over the year in photographs is a healthy exercise for several reasons. First of all, you might be surprised by the number of really good photographs you’ve taken. Hopefully, you won’t be disappointed if they number less than 12—and, if so, ask yourself why? Was it one of those years when family and/or work commitments limited your time spent photographing. If that’s the case, consider building photography into more of a routine in the coming year.

Another image captured with handheld focus stacking, this time with a macro lens.

OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 60mm ƒ2.8 Macro lens; ƒ5.6 @ 1/500, ISO 800; stacked JPEG processed in Lightroom

Do you golf, play hockey or attend a club once a week or take part in another weekly endeavour? Consider trading one of those sessions each month for a few hours out photographing. Try to make it a regular thing, by choosing a series of locations you’d like to visit and going out rain or shine.

Another alternative for increasing the number of photo sessions is to join a local photography club. While they have guest speakers throughout the year, which might provide inspiration, clubs often have field trips, workshops and hands-on learning sessions to broaden your photography. I’ve had people take my workshops for the sole purpose of getting out and photographing.

2024 was the year of the total eclipse here in southern Ontario!

OM-1 w/ 100-400 at 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ16 @ 1/4000, ISO 200 with ND500 + NDx8 filters; raw file processed in DxO RawPrime and Lightroom.

Secondly, looking at a retrospective of the year can give you a sense of where your strengths are, what techniques or styles you enjoy using and, more importantly, what is not working for you. You may have sessions out photographing for which you have no images to consider as your best. Why is that? Was the lighting flat and featureless? Or was there simply nothing compelling to shoot? Perhaps there was something you saw and photographed, but didn’t quite capture what caused you to stop in the first place? These are important developmental questions to consider and are part of the learning journey.

Decades ago, I read an article about Robert Gilka, a long-time Director of Photography at National Geographic. Something written has always stuck with me. He felt there is always a compelling photograph to be captured—it just takes a visionary photographer to see it. Apparently, his test of talent was to give a photographer a roll of black-and-white film, put them in a dark alley, and direct them to come back when they’ve finished the roll. Talk about limitations!

A pair of catbirds frequented the apple tree outside our family cottage, collecting caterpillars and other delicacies to feed their young in the nearby nest. It was just a matter of time before the lighting of early evening (7:20pm) and their perch location was ideal for a photograph.

OM-1 w/100-400mm @ 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/200, ISO 3200; raw file processed in Lightroom.

Ansel Adams often wrote of the value of ’seeing photographs’ even when you’re not photographing. I often see photographs when I’m out driving, but that’s not an entirely safe endeavour. Looking out a window or when out walking, stop and look. Look carefully. In your mind, frame up an interesting pattern or scene. Move forwards, backwards, up and down to compose the photograph. Think through the steps of how you might precisely capture the photograph, what perspective to use, and which focal length would best match that view. It’s a helpful exercise and it doesn’t cost a thing except a moment of your time. In instances like these, once I’ve composed the image, I often take out my phone to make a quick snap.

Choosing photos

If you have plenty of great photographs to choose from, well then that’s a different problem. How do you edit down to just 12? It’s important to look at them, I mean really examine each photograph, closely, looking specifically for flaws. Look at them large, on your TV for example. Check the edges and corners, focus and exposure, horizons, subjects. How is the composition? Rule of Thirds? Foreground, mid-ground and background? An image that initially captures your imagination may in fact have flaws that you first missed because you were taken in by the impact of colours or design or the memory of that significant moment.

There is no right or wrong, and don’t rank them, just choose 12—and learn as you choose. Remember, you’re looking for your 12 best, not 12 perfect photographs. This is especially important if you are new to photography. It’s a learning journey.

Pro Tip: If you are using an editing app like Lightroom, hopefully, throughout the year, you assigned star values to your photos. If not, do so now, at least for the best of the best. This makes selections weeks or months later much easier. Each time I go through a set of images from a photo session, I pick the best by giving them a flag. As I go through them again, I give one star to any worth pursuing with further editing. Once I’ve given a file its first edit, I give it 3 starts. From there, a photograph earns 4 or 5 stars depending on its overall quality and impact.

Once you have your 12 best, consider this—what makes those photographs so successful? To get to the root of your photography, try going beyond ‘location’ or ‘subject’. What ‘worked’ in the photographic sense? Was it the ambience of the time of day or time of year? What about the lighting? The composition? The style? Perhaps all the planets aligned to create a perfect photograph. Drill down to discover: Why? How? As you discover what works, then try to replicate that in future photo sessions.

An adult Pearl-spotted Owlet launches itself from its nest hole in a baobab tree. After seeing the owl with its young in a nearby acacia, and watching the two of them enter the nest, from there, it was a waiting game. Within five minutes, I could see slight movement in the hole, then out flew the adult.

OM-1 w/ 100-400 at 400mm (800mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/800, ISO 1600; raw file processed in Lightroom.

The next 12

Now take a look at the next 12 or 24. Why didn’t they make ‘the cut’? It is just as important to discover what didn’t work, which can provide insights into how you need to improve. Again, don’t consider the location or subject; consider only the photographic elements of composition, lighting, perspective, and editing.

One of my ‘Next 12’. This took some very careful lining up—shifting forward and back, left and rightand finding the ideal focal length—as the sun rose quickly in the morning sky. Hazy smoke from local agricultural burning added the colour.

OM-1 w/ 100-400mm at 210mm (420mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/800, ISO 200; raw file processed in Lightroom.

Take perspective, for example. Not enough is written about ‘where you’re standing and what focal length to use’. Should you have been closer with a wider angle lens to accentuate the foreground? Or should you have been further back with a longer focal length to compress the ‘layers’ of foreground, mid-ground and background?

Fred Picker, the east coast equivalent to Ansel Adams, always felt he had the perfect composition,

“when the scene was looking back at me”.

What an interesting way of looking at perspective and composition. Finding that sweet spot in three-dimensional space is perhaps the most difficult part of photography. Even Ansel Adams recognized,

“A good photograph is knowing where to stand”.

I really am a landscape photographer at heart, though with the addition of a long telephoto zoom, my focus has begun to include birds and wildlife.

OM-1 w/ M.Zuiko 12-100mm at 15mm (30mm efov); ƒ5.6 @ 1/800, ISO 800; Handheld High Resolution; raw file processed in Lightroom.

Whatever you do, DO NOT say or think, ‘If only I had better equipment!’ We all know the adage, ‘a poor carpenter blames his tools’. Just about any camera and lens combination manufactured today—from 1” sensors to Micro 4/3s, APS, and full-frame—will produce sharper photographs and consistently more accurate exposure than any large format equipment Ansel Adams was using.

We really are in the Golden Age of photography. Technology has progressed to provide us with unparalleled image quality, so don’t be too quick to blame your equipment. Learning how to use what you’ve got—camera, lenses, editing app—more effectively and efficiently may be the direction you are headed in this coming year. However, it may be helpful to recognize when you consistently find the need for a wider angle lens or a longer focal length than you have. Too often equipment purchases are based on the whim of ’want’. Looking back at your photos and analyzing them may lead to better insights as to what you would find useful.

At 6:26pm, as the sun set on what was an amazing day of lion-spotting in Tarangire, this male lion got up from its sleep on the sandy river bank to make his presence know to a female lion in the tree above him. Laura manoeuvred the safari truck into just the right position to capture him looking out over the plains.

OM-1 w/ 100-400mm at 300mm (600mm efov); ƒ8 @ 1/80, ISO 3200; raw file processed in DxO PureRaw and Lightroom; up-scaled 2x in Lightroom—more on that process in a future blog.

So, now that you have the best of your best photographs, it’s time to make something of them. Two options spring to mind: make a calendar of your 12 best or make a photo book of your 20 best. Most photo books come with 20 pages, so you may as well fill them—but only with your 20 best! Make them full page, with a ½” to 1” white border, so they look like matted photographs. Add a title to the bottom right, something that reminds you of what, where, and when. Don’t try to squeeze in 25 or 30 photos as that will detract from showing your best.

Each year going forward, do the same and watch how you and your photography grow and change. It sounds trite, like school pictures collected by your parents over the years, but it will all make sense and become a point of pride as each year you add another volume to your series.

Good luck, and all the best for a great 2025!

Twelve minutes after sunset—sunset at the Equator is consistently around 6:30pm and is almost instantaneous—and the blue zone is upon us, much faster than here in Canada. Who should show up, but a giraffe. How fortunate!

OM-1 w/ 12-100mm at 100mm (200mm evof); ƒ5.6 @ ⅓ sec., ISO 800; raw file processed in DxO RawPrime and Lightroom.

Note: in this case, Handheld High Res mode could not be used due to the movement of the giraffe. However, the file was successfully up-scaled to 10368×7776 pixels (80.6MP or 34.5” x 26” print) using Lightroom’s Enhanced Super Resolution of the DxO DNG file. More to come on that process in a future blog post!

Discover more from luxBorealis Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Trackbacks